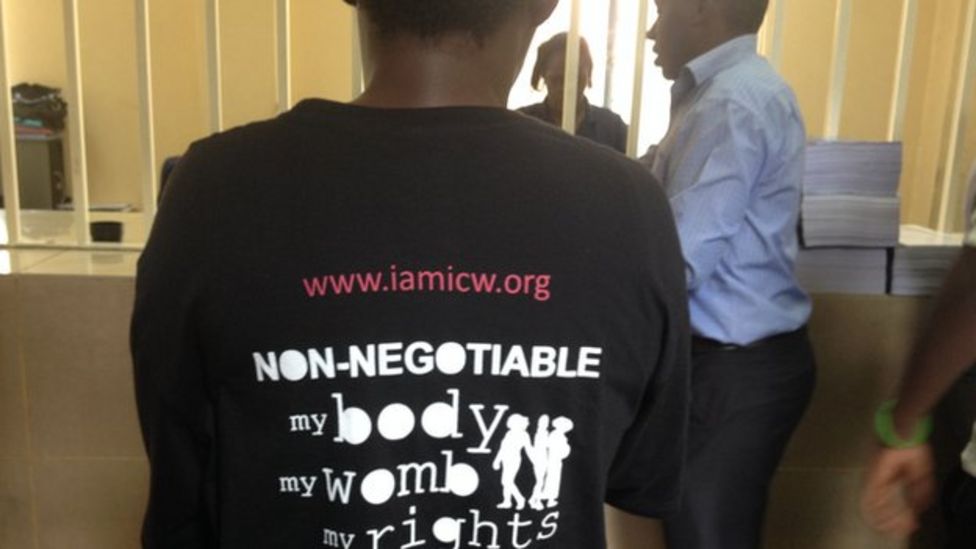

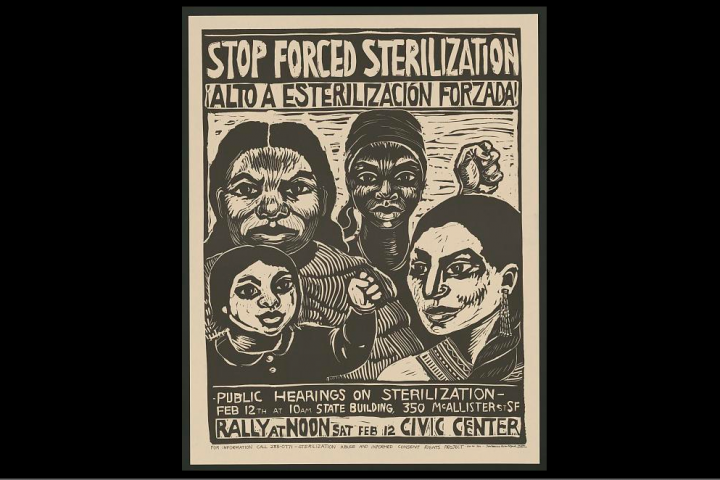

Nine years ago, almost to the day, five women wearing t-shirts walked into a Nairobi court. On the back, the t-shirts read: “NON-NEGOTIABLE: my body my womb my rights.” On the front, the t-shirts read, “END FORCED AND COERCED STERILIZATION OF WOMEN LIVING WITH HIV”. In September, finally, Kenya’s High Court ruled in their favor, awarding each 3,000,000 Kenyan shilling, or approximately $20,000. This is the second such case in Kenyan history. In December 2022, another Kenyan woman was also awarded 3,000,000 shilling, also for a sterilization without informed consent. So, 3,000,000 shilling, or $20,0000, is the going rate of `compensation’ for violence against women.

We wrote about the case nine years ago. We began writing about forced sterilization in 2012, concerning a case in Namibia, a case to which we returned in 2014. At that time, we argued that the decision in favor of the three women who had sued the State was “a victory for HIV-positive women, for all women, everywhere”. A decade later, we wonder if that declaratino of victory was perhaps a bit premature. Why does it take nine years for the High Court in Nairobi to decide the case, especially when one considers that the final decision absolves the State of all responsibility?

In 2014, we wrote, “The news this week from Chhattisgarh, India, is tragic. At latest count, 15 women have .died in a `sterilization camp’. Fifty others are in hospital, with at least 20 in critical condition. At first the operations were widely described as `botched.’ After only preliminary investigations, the response moved from `botched’ to `criminal’ and `corrupt’. Finally, the reporting has landed on how Indian this all is. It’s not. Forced sterilization of women is a global phenomenon, actually a global campaign, and it needs to be addressed, immediately. The women, all poor, of Chhattisgarh are part of a global public policy in which women’s bodies are, at best, disposable and, more often, detritus.” It’s now 2023, moving into 2024. Why did it take nine years for a High Court to decide?

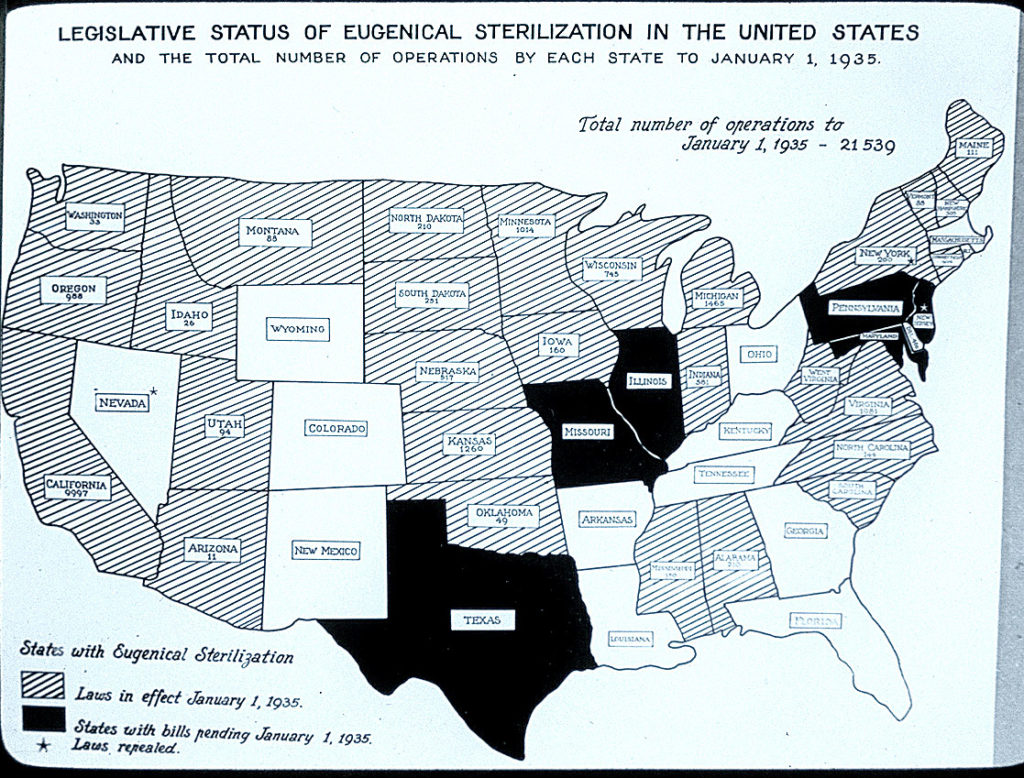

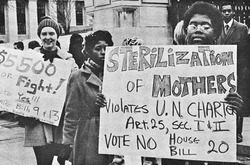

In late September 2014, California formally banned forced and coerced sterilization of women prisoners … again. Then Governor Jerry Brown signed Senate Bill No. 1135 into law. The bill read, in part: “This bill would prohibit sterilization for the purpose of birth control of an individual under the control of the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation or a county correctional facility, as specified.” Not forcing sterilization on women prisoners seemed pretty straightforward. Some would even say a no-brainer. And yet, that law took a lot of brains, and muscle and organizing and history. Think about the brains, muscle, organizing and history it took and takes for a group of women, say in Kenya, to discover they’ve been sterilized, without their knowledge much less informed consent; find the means to take the State and so-called health providers to court; and then to wait, not idly but rather mobilizing the entire time, for nine years.

That all happened before the Kenyan women went to court. Since then …

On February 26, 2015 the Virginia legislature agreed to pay $25,000 in compensation to those who had suffered forced sterilization during the Commonwealth’s decades long adventure in eugenics. What’s the rate of exchange between 2015 and 2023? Apparently $25,000 to $20,000.

In March 2015 in South Africa, 48 women living with HIV and AIDS responded to the indignity and abuse of forced sterilization. Represented by Her Rights Initiative, Oxfam, and the Women’s Legal Centre, 48 women who had suffered forced sterilization in Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal came forward and lodged a formal complaint. These 48 `cases’ were from 1986 to 2014. Their case has been reported on, fully researched, and documented. As of now, they have received neither compensation nor a formal apology of any sort.

In March 2019, all major parties in Japan agreed to pass a measure that would “deeply apologize” and offer compensation to victim-survivors of forced sterilization. The compensation would be a one-off payment of around $28,700. Now we know the value of life in Japan … and beyond. What is the price of a `deep apology’ when made to women?

On May 26, 2022, Colombia’s newly elected President Gabriel Boric announced, “I would like to start by apologising to Francisca …. for the serious violation of your rights and also for the denial of justice and for all the time you had to wait for this. How many people like you do we not know? It hurts to think that the state, which today I have the honour to represent, is responsible for these cases. I pledge to you, and to those who today represent you here in person, that while we govern, we will give the best of each one of us as authorities so that something like this will never happen again and certainly so that in cases where these atrocities have already been committed, they will be properly redressed.”. Boric went on to promise to provide specialist training to medical workers on HIV/AIDS to curb discrimination and to ensure that judges and lawyers are aware that affected women have a right to reparations. Who is Francisca?

In 2002, a 20-year-old, married rural woman known as Francisca discovered she was pregnant. She and her partner were elated. When, early in the pregnancy, Francisca went in for tests, she discovered that she was HIV positive. She immediately began a protocol of antiretrovirals. She had a caesarean delivery, successfully, and the child was HIV negative. That child, now 22 years old himself, is still HIV negative. When Francisca emerged from the surgery, a nurse informed her that the surgeon had sterilized her. Francisca never asked for or wanted to be sterilized and had never consented. In 2007, Francisca sued the doctor. In 2008, the case was dismissed. In 2009, the Center for Reproductive Rights and Vivo Positivo took the case, on Francisca’s behalf, to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. In August 2021, the Chilean government signed a settlement accepting responsibility and offering something like reparations: a housing subsidy and healthcare for both Francisca and her son as well as a commitment to raise awareness of HIV and reproductive rights … after thirteen years.

In Peru, from 1996 to 2001, the Peruvian government, under the leadership of Alberto Fujimori, forced at least 2000 indigenous women to undergo forced sterilization … all in the name of family planning. In 2018, Fujimori and his accomplices were informed they would be facing charges. That case basically ended in mistrial. In September 2023, the same month in which the Kenyan women heard they would be receiving `compensation’, the daughters of Celia Ramos, who died in 1997 days after being forcibly sterilized, learned the Inter-American Court of Human Rights will hear the case.

In all of these cases, the justification, if any was even given, included public health, family planning, protection of the individual women. Society must be protected. In each case, the procedure was conducted by trained medical personnel. Women have been subjected to the torture of forced sterilization for a myriad of reasons and, ultimately, for no reason at all. You want to know why it takes the court so many years to adjudicate these women’s complaints? You want to know why it takes so long for these women to find even a modicum of justice? No reason at all.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Photo Credit: BBC)

.jpg)