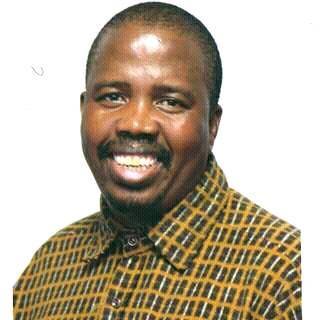

Tembinkosi Qondela

We didn’t get to finish

We didn’t get to finish

a social media dialogue

in between the music

I sent TQ to keep

our spirits up

We didn’t get to finish

he asking leading questions

in response to my saying

that I miss the schoolchildren

What will you do he asks

when most are infected

the school has to close

and you can’t even

visit them at the hospital

Children whose nutrition

and immune system

is compromised are also

vulnerable and then they

bring it home to those

who are more vulnerable

Whizz Centre suspended classes

for 60 of their learners

who were a major source

of the Centre’s income

putting people’s health first

This is the TQ we knew

health before profit

health before economy

not economy before health

he maintained you cannot sacrifice

people’s health for the economy

Then he asks me

what is this economy

we are talking about

are we talking about

food or gold

We didn’t get to finish

(Photo Credit: Facebook / Tembinkosi Qondela)