He said he didn’t know

There are many

who are there

right here

out Africa-way

Knowing

knowingly

and not knowing

in denial

and denying

they are beyond too

on the rest

of Planet Earth

He said he didn’t know

the little enclave’s last

does as many have done

and many will continue to do

Might Ladysmith Black Mambazo’s

haunting Homeless

be a reminder

a little hint

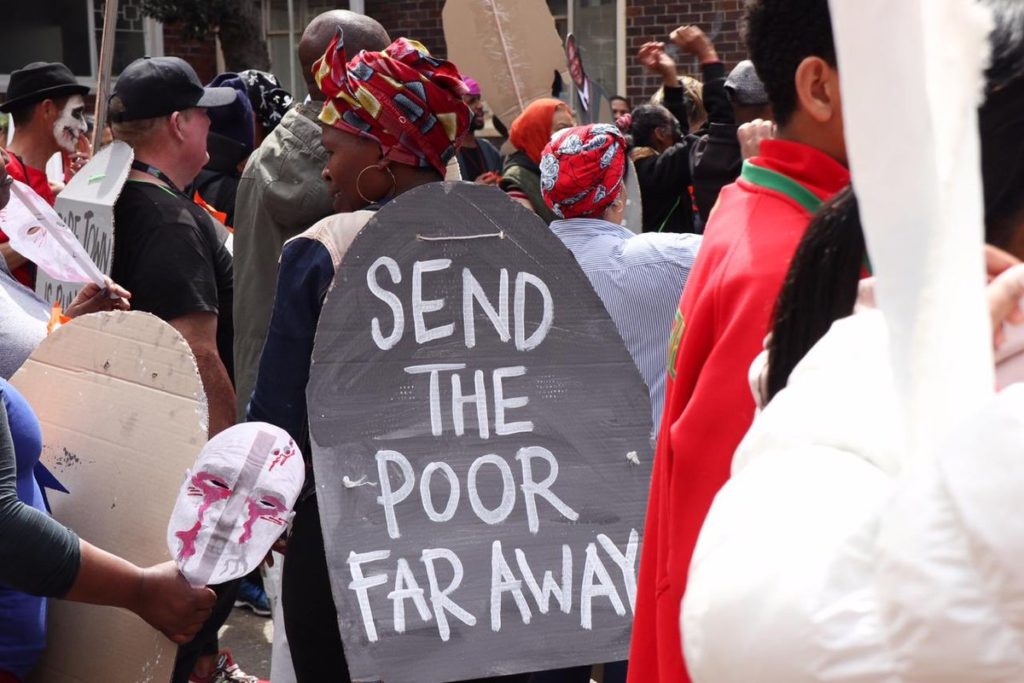

that the system

he oversaw

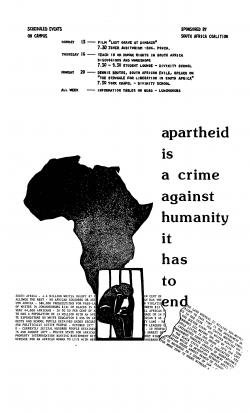

had been declared

a crime against humanity

some even have it

that it was

an unfortunate past

a glitch on the horizon

of the planet’s timeline

like the Little Troubles

over in (Northern) Ireland

like the fall of Saigon

(and not the people’s struggles

against various imperialisms)

He said he didn’t know

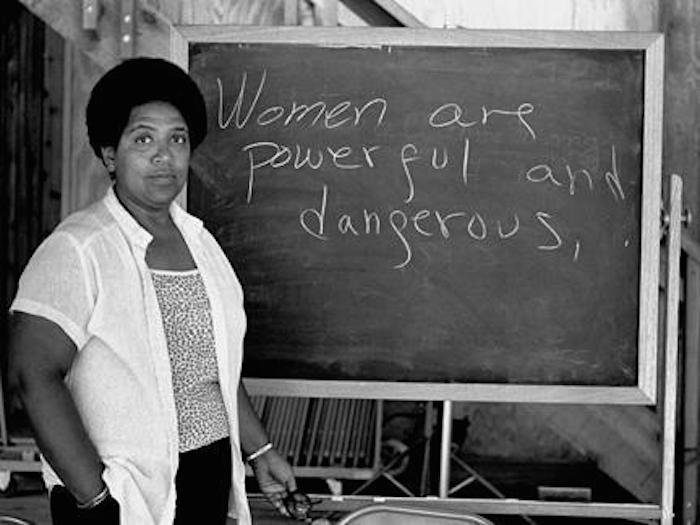

notwithstanding the scars

the scarred and the scared

still

(Image Credit: African Activist Archive)