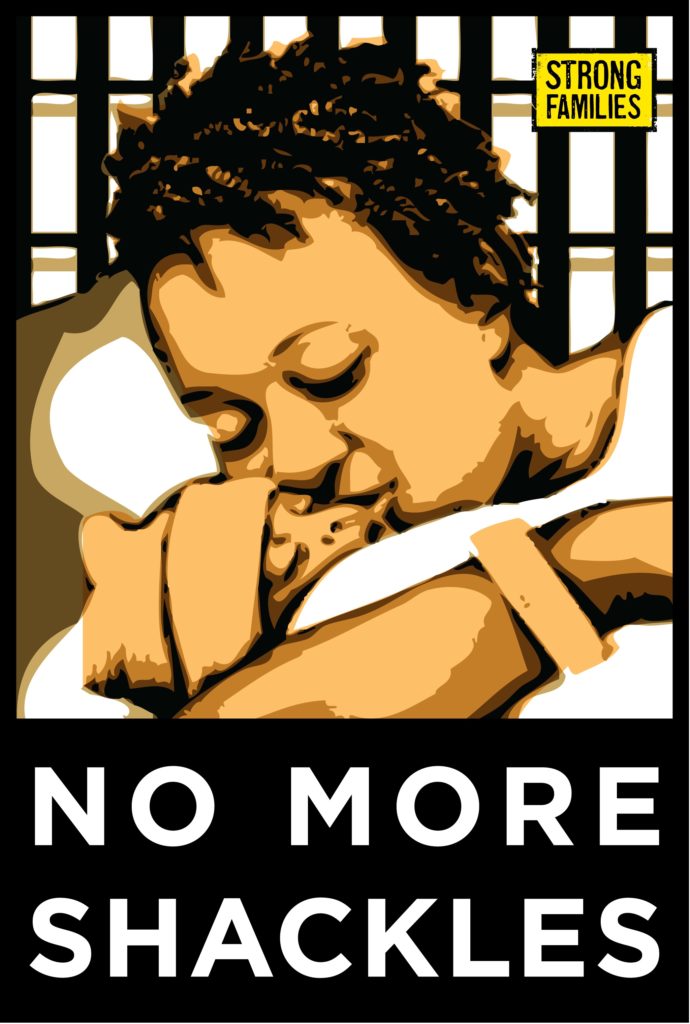

Yesterday, March 26, 2018, the North Carolina Director of Prisons officially ended the shackling of women (prisoners) in childbirth. This came after SisterSong and other members of the Coalitions to End Shackling in North Carolina sent a letter to the North Carolina Director of Prisons, which read, in part: “The North Carolina Department of Public Safety prohibits the use of shackling during delivery and yet in recent weeks at least two people from North Carolina Correctional Institute for Women were restrained throughout their laboring process at a local medical center. This was in spite of the concerns of medical staff and the fact that it was in violation of NC Department of Public Safety written policies and legal precedent.” After two months `deliberation’, the North Carolina Director of Prisons agreed. In so doing, North Carolina joins 22 states that currently prohibit or limit the shackling of pregnant women. While there is cause for celebration, why do more than half the states in the United States allow women (prisoners) to be shackled during childbirth?

The letter from SisterSong and the coalition noted that shackling people during and after childbirth is “inhumane and unsafe”; that no state that has banned shackling has suffered any negative consequences; that the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has long opposed shackling; that “shackling interferes with the ability to properly treat and care for people and to respond to crisis situations”. Along with doctors, the courts have found that shackling violates the right to be free from cruel and unusual punishment. Further, “with people of color overrepresented in the prison system, this issue falls hardest on people who already struggle with health disparities and higher rates of pregnancy complications and maternal mortality.”

The letter concluded, “We are demanding that the policy be updated to be brought in line with the best practices and recommendations of health professionals and that training be provided to ensure that it is implemented consistently. This practice serves no public benefit. It does, however, risk harmful impacts on individuals and their children. It is not only bad health policy, it is a violation of individual’s human rights.”

Last year in North Carolina, 81 women (prisoners) gave birth … shackled. As of a month ago, North Carolina prisons “boasted” 50 pregnant women.

According to Omisade Burney-Scott, director of strategic partnerships and advocacy for SisterSong, explained, SisterSong wants to ban shackling “throughout the entire pregnancy, so during prenatal care, labor and delivery, postnatal, out to eight weeks and also during breast feeding.” In Kentucky, State Senator Julie Raque Adams filed Senate Bill 133, known as the “Dignity Bill,” which would prohibit shackling of women prisoners in childbirth. Currently, the bill is “one floor vote away” from passage. Georgia and Connecticut are considering bills that would ban the shackling of women in childbirth.

Women prisoners are women. It is wrong and harmful to shackle pregnant women. It is right to support women’s right to health, well-being, and being women. So, thank you to SisterSong and their allies. Thank you to State Senator Julie Raque Adams and her allies. Thank you to North Carolina and Kentucky. Last year, Senators Cory Booker and Elizabeth Warren introduced the Dignity for Incarcerated Women Act, “requiring the Federal Bureau of Prisons to consider the location of children when placing mothers behind bars, expanding visitation policies for primary caretakers, banning shackling and solitary confinement for pregnant women, and prohibiting prisons from charging for essential health care items, such as tampons and pads.” The clock is ticking. End the shackling of pregnant from sea to shining sea.

(Image Credit: Radical Doula) (Infographic Credit: Nursing for Women’s Health Journal)