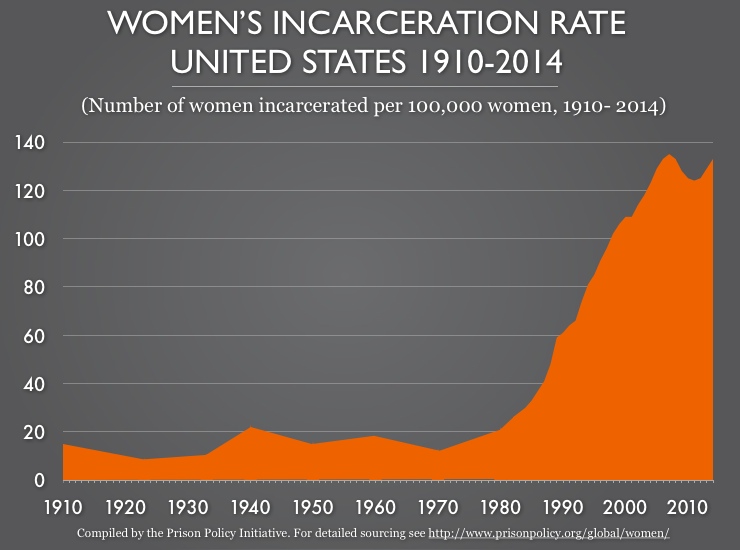

In the United States, jails are filling up, with particularly catastrophic consequences for women. Caging more and more women in jails for longer and longer periods of time is how the State protects its interests … and `its women.’

The Vera Institute released a report last week on the misuse of jails in the United States. It details the ways in which jails have become the repository for the poor, mentally ill, of color. For women, the situation is dire: “Serious mental illness, which includes bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and major depression, affects an estimated 14.5 percent of men and 31 percent of women in jails—rates that are four to six times higher than in the general population … While most people with serious mental illness in jails, both men and women, enter jail charged with minor, nonviolent crimes, they end up staying in jail for longer periods of time. In Los Angeles, for example, Vera found that users of the Department of Mental Health’s services on average spent more than twice as much time in custody than did the general custodial population—43 days and 18 days respectively … Although women still make up a relatively small proportion of the jail population—14 percent in 2013— their share has been steadily increasing, up from 11 percent since 2000 … In 2005, 79 percent of women in jail were mothers, with nearly 250,000 children between them.”

The key here is serious mental illness affects 31 percent of women in jails. Mental illness has a gender here, and it’s women. Somehow, that salient feature drops out of the various news reports, which focus on the warehousing and punishing of the poor for their poverty and often of people of color for their race and ethnicity. Women, mostly poor, mostly women of color, and an extraordinarily high number of whom are living with mental illnesses, are being piled into jails across the country, in increasing numbers and for longer periods of time. As the Vera report notes, the money that pays for this adventure comes from “the same pool of tax revenue that supports schools, transportation, and an array of other public services.” So, first cut the services that might help these women, then pop them in jail, and then, in order to pay the freight, cut the services even further. And for the quarter million children, who are left behind, show no mercy.

Women haunt the entire prison project of the United States. Last month, California `celebrated’ its prison population dipping below the federally mandated level, which is 137.5 percent of capacity. So, the prison system is still overcrowded but not unconstitutionally so. The one exception here is the Central California Women’s Facility, the largest women’s prison in the world, built to house at most 2,000 prisoners. It currently has 3,383. That’s almost 170 percent of capacity, but it’s not cruel and unusual. It’s cruel and usual. The same is happening in the more than 3000 city and county jails across the country. It’s cruel and usual, and so it’s fine.

(Infographic: Prison Policy Initiative)

(Video Credit:

(Video Credit: