Cori Bush

“The Mafia is not an outsider in this world; it is perfectly at home. Indeed, in the integrated spectacle it stands as the model of all advanced commercial enterprises”

Guy Debord: Comments on the Society of the Spectacle

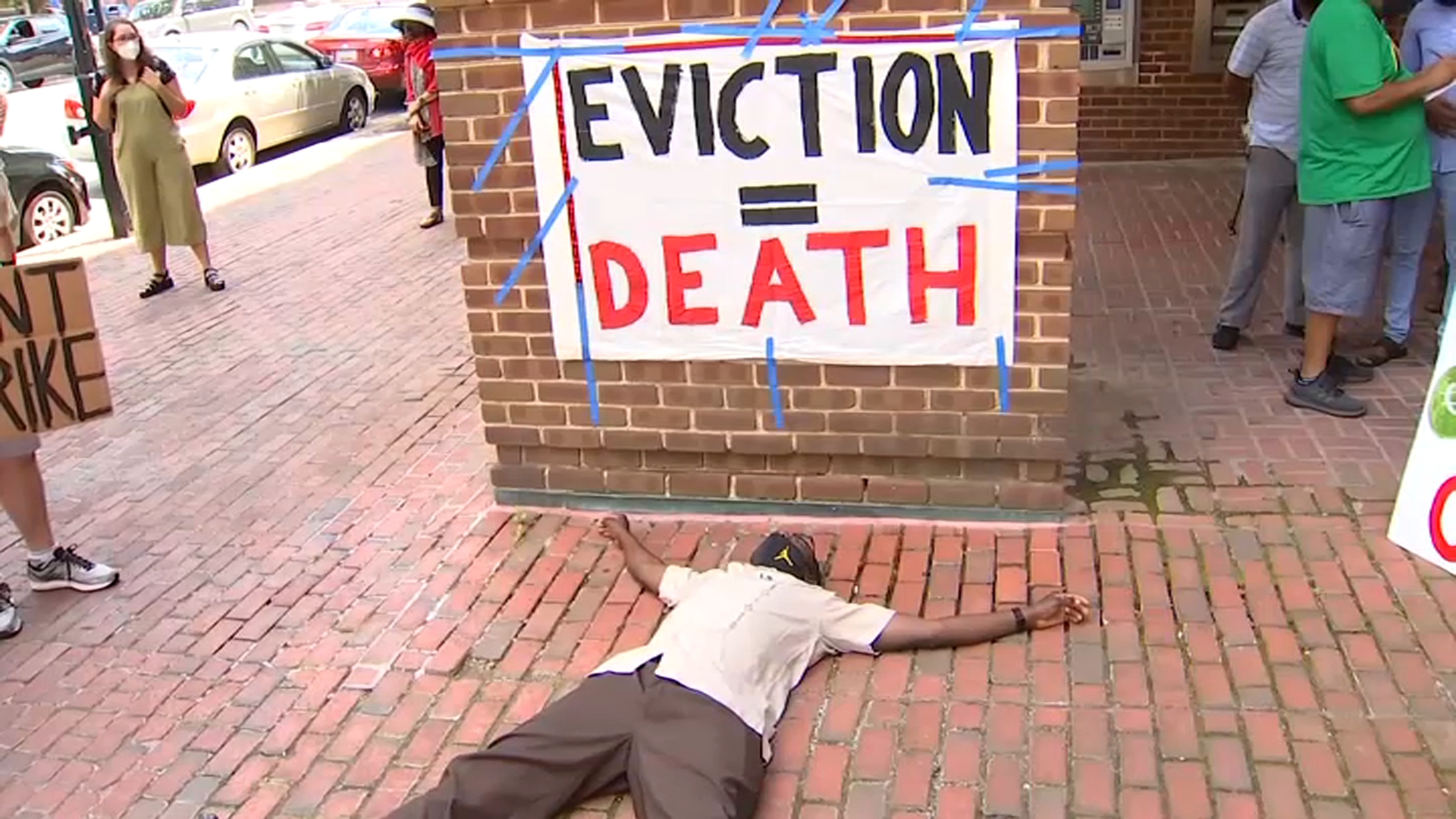

At midnight Saturday, as July turned into August, the CDC moratorium on evictions ended. On Tuesday evening, the CDC announced a new set of protections from evictions for those living in communities suffering substantial to high incidences of Covid. This is a 60-day reprieve for which we all owe Representative Cori Bush more than a great deal of thanks. She lit a path out of the darkness, in more ways than one. Cori Bush taught us humanity matters, Black women matter, Brown women matter, Black and Brown children and communities matter, humanity matters. We need that lesson, desperately, as we slog, drenched, in a national theater of cruelty. Consider what happened between midnight, Saturday night, and Tuesday evening. Consider the spectacular, and spectacularly ordinarily cruelty, that greeted and awaited the most vulnerable among us.

St. Louis already had 126 eviction orders pending, and more promised, lots more. In response, St. Louis Sheriff Vernon Betts announced that he would triple his eviction crew. Sheriff Betts hoped to conduct as many as 30 evictions per day, starting August 9. He explained, “Right off the bat we want to clean up that 126 evictions.” Removing people from their homes in the middle of a pandemic has become an act of cleaning up, if not cleansing.

In New Orleans, located in the epicenter of the current Delta variant crisis, Constable Edwin M. Shorty Jr. issued an order. In order to facilitate the anticipated heavy eviction workload, all full-time and reserve deputies had to be vaccinated by August 16. On Monday, New Orleans’ busiest housing court 58 eviction filings, up from the pandemic moratorium average of one a day. The headline more or less says it all: “New Orleans landlords take advantage of eviction moratorium’s end, file to eject dozens”.

Lest anyone feel geographically smug, on Monday landlords rushed to file evictions in Rhode Island, Ohio, North Carolina, and Florida. In Idaho, where judges had never recognized the moratorium, it was eviction business as usual. In Connecticut, eviction orders spiked: “Before the federal order was reinstated Wednesday, judges in Connecticut signed a surge of orders that allow state marshals to remove tenants and their belongings from their homes….The 154 families that judges gave the nod to be evicted Monday and Tuesday is double the number of evictions that were being granted in recent weeks. It also mirrors pre-pandemic eviction levels.” Look in that mirror, do not look away. In Delaware, “new eviction filings … spiked to a level not seen since March 2020.” Is this the much heralded return to normal? In Pittsburgh, “on Monday, a day after the federal eviction moratorium ended, court filings to evict people increased 420%.” In Harris County, Texas, there have been 254 eviction filings, between Monday and Thursday of this week. What eviction moratorium? What tenant protections? Where? Not here. Not wherever you’re sitting right now, reading this.

In Georgia, on Friday, July 30, hours before the CDC moratorium would end, faced with 145 writs of eviction and 1650 writs pending, DeKalb Chief Superior Court Judge Asha Jackson signed a new emergency order creating a ban on evictions throughout the county for another 60 days. In her order, Judge Jackson noted, “Without an eviction moratorium, many DeKalb County residents face imminent dispossession of their residences due to widespread arrearages owed to landlords. It is estimated that DeKalb County tenants owe approximately $50,000,000.00 in rent arrearage to landlords. Many of the landlords owed will be legally entitled to proceed with dispossessory actions once the eviction moratorium is lifted. Evictions can have long-lasting consequences for families and individuals, potentially disrupting school and education, worsening health, displacing neighborhood networks of support, and making it more difficult to find safe, affordable housing in the future. Perhaps most importantly, a lack of stable housing directly increases the risk of contracting COVID-19.”

Some people prepared by increasing their eviction crews, others by telling them to `man up’ and take the jab, others by pushing paper as quickly as they could. Other people, like Cori Bush and Asha Jackson, looked at the need, despair, pain, suffering, fear, terror, destruction, they looked at the human tragedy unfolding and they said NO to the inevitability of power, NO to the Mafia model governance, and YES to humanity. Which side are you on?

DeKalb Chief Superior Court Judge Asha Jackson

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Photo Credit 1: Matt McClain/The Washington Post) (Photo Credit 2: Atlanta Journal-Constitution)