Your sole is broken

A fellow traveller

(a woman to boot)

observes as I stoop

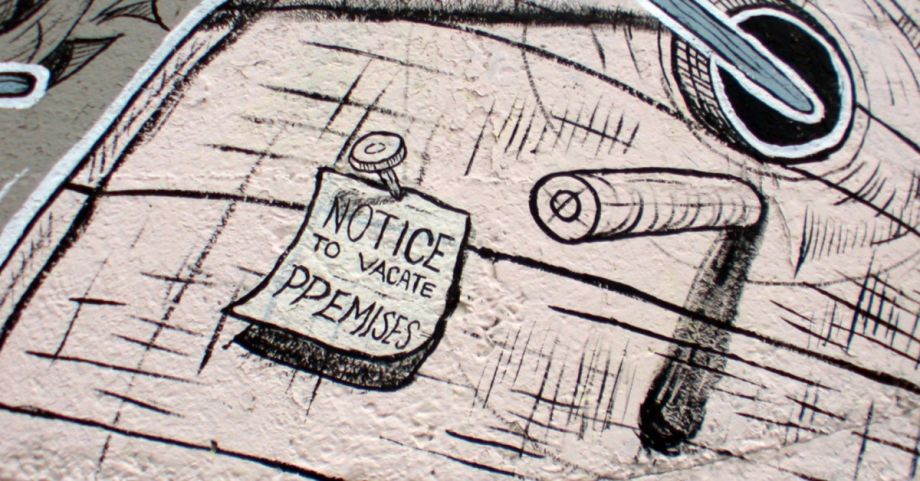

to examine the sole

of an age-old boot

Knee-high they are

rescued me many times

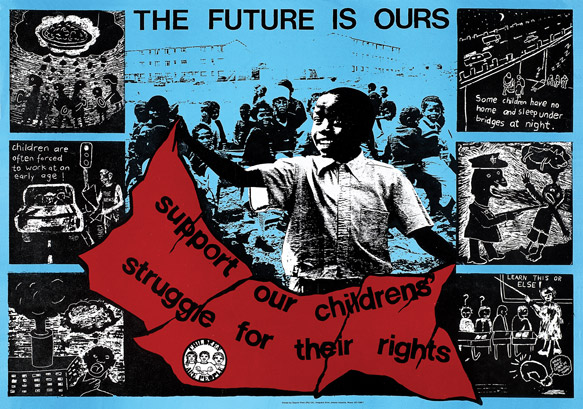

from the searching hands

of apartheid’s police

(contraband stuffed

down my length of leg

the side-pockets usually

filled with meeting notes)

Your sole is broken

couldn’t keep up

with my striding

here there and

whereever too

Your sole is broken

perchance a slip

of the Freudian variety

in these challenging times

(who would have thought

as we are supposed to be

free from all iniquities

post-1994’s Majority Rule

Your sole is broken

can it be fixed

(do we actually want to

and at what cost)

or is it beyond repair

(By David Kapp)

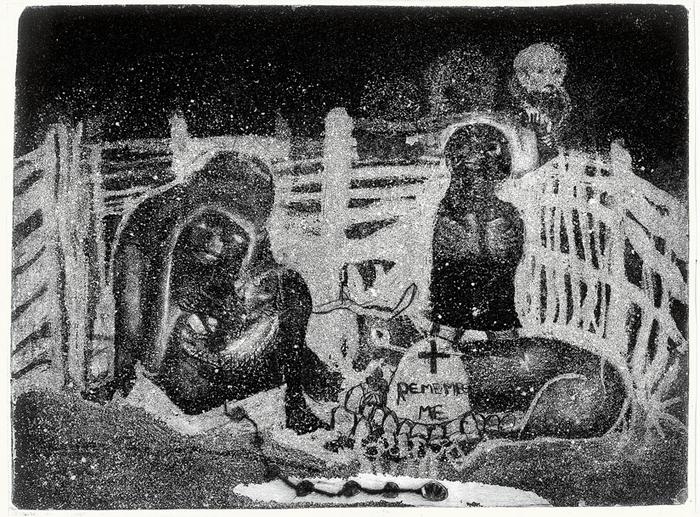

(Image Credit 1: Community Arts Project / UWC Centre for Humanities Research) (Image Credit 2: Community Arts Project / UWC Centre for Humanities Research)