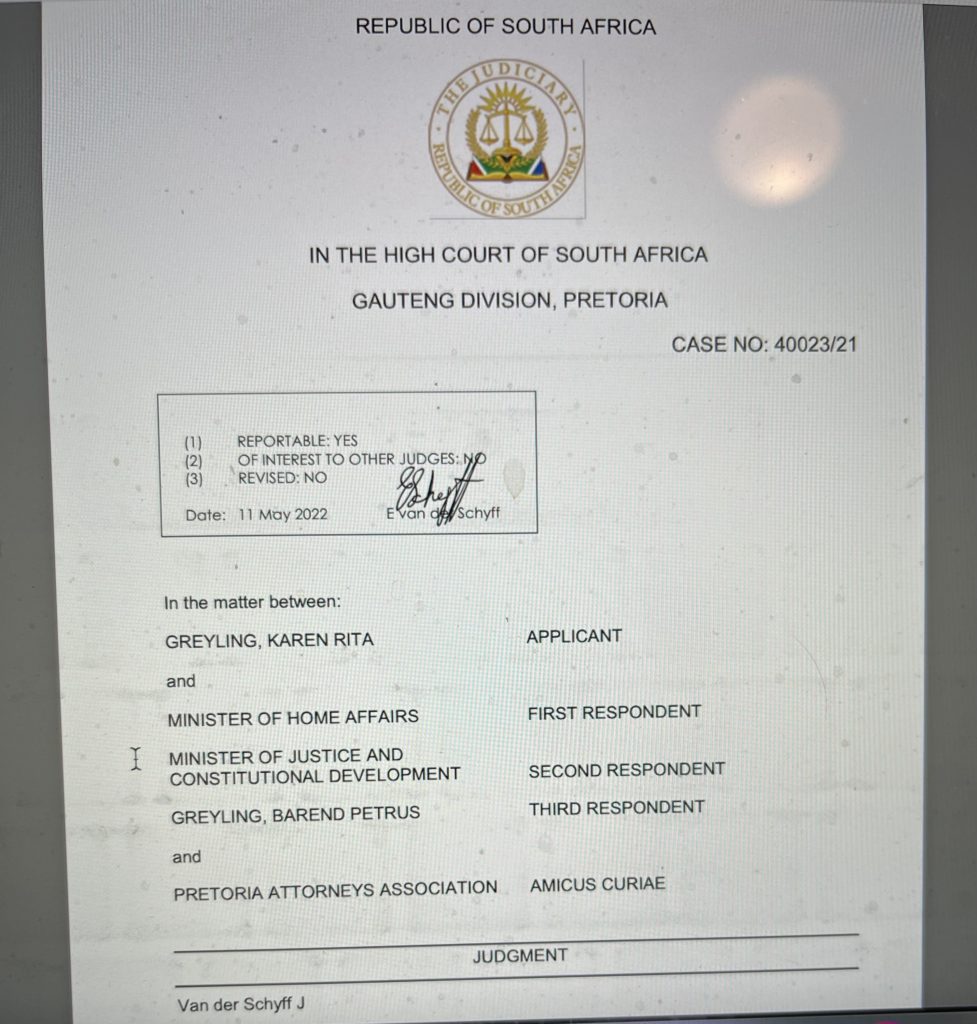

In South Africa, Karen Greyling argued that any system, any Constitution, that leaves women economically trapped in toxic marriages is unconstitutional. On May 11, the Gauteng Division of the High Court of South Africa agreed. Near the end of her 40-page decision, Judge Elmarie van der Schyff noted, “Aspects like the now abolished marital power and the man’s headship of the family are factors that contributed, and continues to play a significant role in the way some men, and even women themselves, regard the roles, and stature of women in society. Only those who go blindfolded through life can deny that gender equality has not yet been achieved in South Africa. In fact, the South African society still has a long way to go.” Karen Greyling said enough is enough. Beverly Clark, specialist family lawyer Beverley Clark of Clarks Attorneys, who agreed to take on the case, agreed. Judge Elmarie van der Schyff agreed as well. Now the case goes on to the Constitutional Court. Here is the story of a woman who said, no matter what the Constitution said, inequality is a violation of her rights and she demanded justice.

In March 1988, Karen and Barend Petrus Greyling were married “out of community of property, excluding the accrual system”. When it comes to assets and liabilities, and especially as pertains to divorce, South Africa has three marriage regimes: in community of property, where both parties share in liabilities and assets; out of community of property with accrual, where parties stipulate assets to be excluded, declare asset values, so that, in the case of divorce, only the accrued estate will be shared; and out of community of property, excluding the accrual system, in which each party has their own estate, and that’s that, no shared assets or liabilities. This third category was added in November 1984, with the enactment of the Matrimonial Property Act 88 of 1984.

In 1988, Karen Greyling was 22 years old. A little before the two married, Barend Greyling’s father announced the marriage would be no community property, no accrual. The lawyer presented the 22-year-old with a one-page contract, she signed, and the deal was done.

The couple lived in a rural area. They had three children. Karen Greyling took care of the children and of the house. Barend Greyling became a very successful, award-winning farmer. They were rich. Actually, he was rich. The relationship became toxic and abusive. In 2016, the couple separated. It was then that Karen Greyling, thirty years later, learned the meaning of “out of community of property, excluding the accrual system”. Other than a small inheritance from her mother, she had nothing.

Karen Greyling knew that was wrong. She searched for an attorney. Many turned her down, explaining the law was not on her side. Finally, Beverly Clark took on her case: “My client went to a number of attorneys who told her she didn’t have a case. Eventually she came to me in 2019, and I was keen to take this on because I have always thought the law was unfair. I have had so many clients where the woman got such an unfair deal. Many women who have been homemakers are trapped in unhappy or abusive marriages because they know they will walk away with nothing.”

Karen Greyling’s attorney argued, “The blanket deprivation of excluding spouses from the potential benefits of a just and equitable redistribution order constitutes unfair discrimination based on sex, gender, marital status, culture, race, and religion. As a result, it operates to trap predominantly women in harmful, and toxic relationships when they lack the financial means to survive outside of the marriage.” They argued that the law was unconstitutional. As Beverly Clark later explained, “This is not about bread and milk money. It’s about proper compensation and it’s about the courts being allowed to step in and exercise discretion to avoid unfairness.”

They took the case, finally, to the High Court, where Judge Elmarie van der Schyff agreed. Twenty five years of false promises and blindfolds threw women either into effectively forced marriages or deep poverty while denying their agency and contributions. As Judge van der Schyff noted, “The equality issue brought to the fore in this application is not solely attributable to race or gender or religion, but also to economic inequity.”

South Africa’s Bill of Rights, Chapter 2 of its Constitution, begins its enumeration of rights with Equality: “Everyone is equal before the law and has the right to equal protection and benefit of the law.” Equality is followed immediately by Human Dignity: “Everyone has inherent dignity and the right to have their dignity respected and protected.” These are the first articulations of “everyone” in the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa. In March 2021, the Constitutional Court rendered a landmark decision in favor of five women who had been excluded from inheritance on the basis of gender. In December 2021, the Constitutional Court rendered a landmark decision in favor of survivors, the majority of whom are women, excluded from inheritance on the basis of formal rituals. In May 2022, the High court rendered a landmark decision in favor of women seeking equality in marriage and divorce. Everyone is equal before the law and has the right to equal protection and benefit of the law. Everyone has inherent dignity and the right to have their dignity respected and protected.

(By Dan Moshenberg)