Watch where you walk

Watch where you walk

we are advised

by folks in the know

don’t do a midnight

or an early hours one

(boyfriends bury

their girlfriends

in backyards)

don’t frequent the hotspots

police cannot be everywhere

behind closed doors

in gated mansions

in ivory towers

be-suited in committees

(you know dangerous areas

places like home like school

like the workplace like)

Watch where you walk

twin knifes mom and sister

famine on the horizon

for millions of children

(what way our grant fiasco)

femicide is the order

women besieged

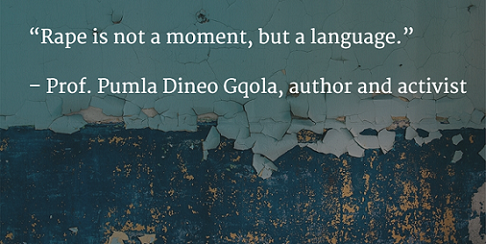

sexual assault the daily custom

(in the broad light of day)

(a woman or girl raped

every 25 seconds down here)

Watch where you walk

International Women’s Day

and our 16 days anti-abuse campaign

has long since passed us by

Watch where you walk

‘Watch where you walk’ – cops (People’s Post Athlone, 14 March 2017). “Boyfriends bury their girlfriends in backyards” (Cape Times, January 31 2017), “Twin ‘knifes’ mom, sister” (Cape Times, February 6 2017); and “Millions of children are facing famine” (Sunday Argus, January 29 2017)

(Image Credit: 702)