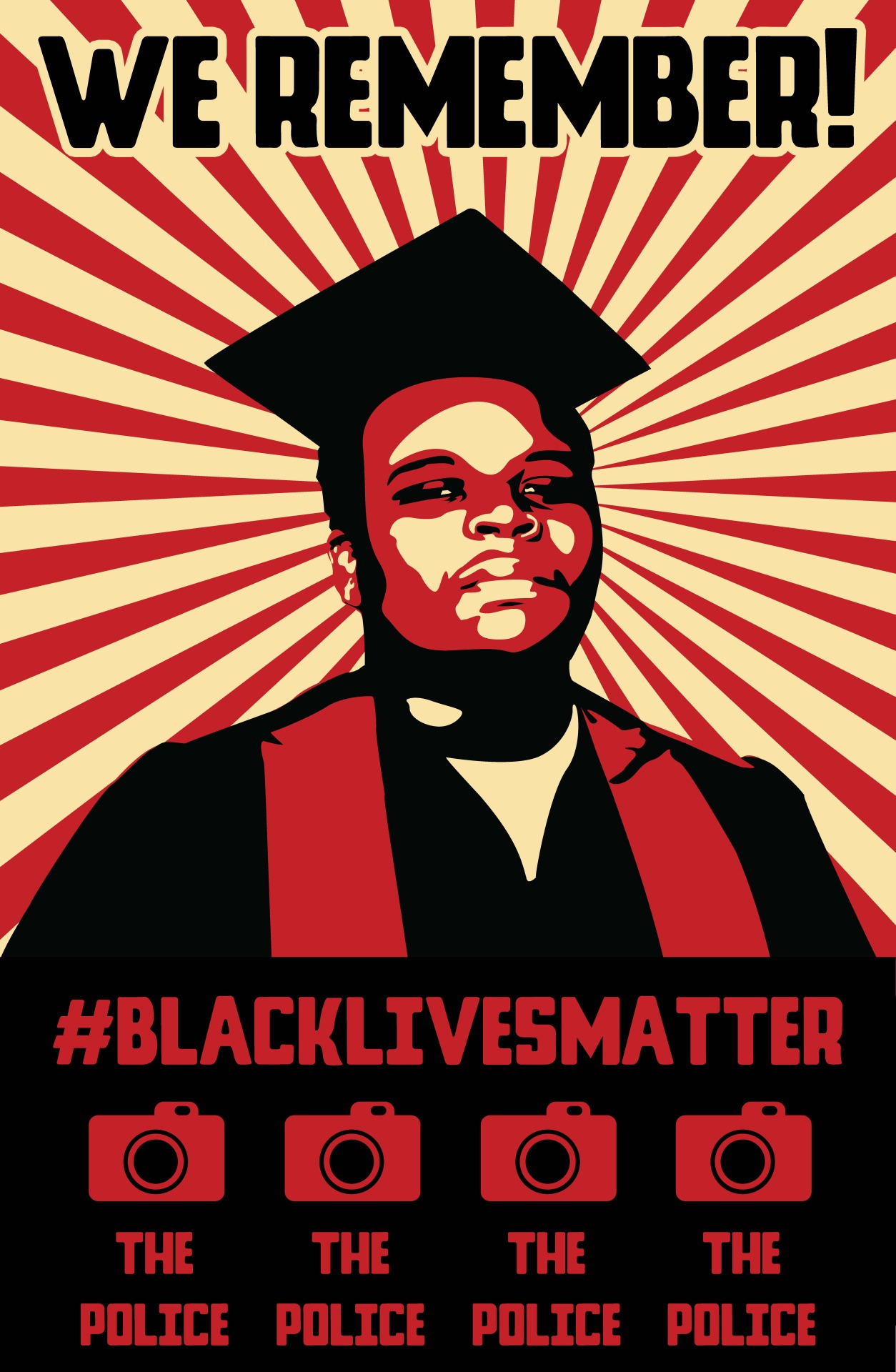

The march against the shooting of Michael Brown, an unarmed black teenager by cops, was well underway in cities across the United States in December. Earlier in the year, there were many more such marches, that both mourned the killing of Trayvon Martin, which had taken place a year earlier, and also sought to bring attention to an epidemic of the shooting by police of innocent teenagers, all black, that is sweeping across black neighborhoods, especially in poorer areas. While one such march was going to take place in New York, right after the officer who shot Brown was exonerated, two police officers in Brooklyn were shot in their police car at point blank range by a black man and later declared dead. Chased by police, the killer shot himself in the head and was later pronounced dead.

The outrage against the killing of the cops was understandable. What was surprising was that people who spoke out against the cop killings said that the anti-police march was an abomination for it showed no respect for the tough work that police had to do in crime-ridden neighborhoods. Journalists in mainstream TV stations started repeating the mantra of “anti-police march” and rhetorically answering their own question of whether such a march conflicted with the “assassination” of the cops. A couple of days later there was a march in solidarity with the cops who were killed in the line of duty.

There are several problems with this line of thinking:

First, why should the killing of the cops obliterate the question of justice that is central to the killing by cops of unarmed black teenagers? Clearly, there is a difference between an armed man who killed the cops and the unarmed black teenagers who were being targeted and killed by the cops. And why should a march that questions the justice meted out to the Brown family be called “anti-police”? When journalists use such terms they whitewash the very essence of what the protest against police brutality is about.

Second, why is the killing of the Brooklyn cops called an “assassination,” but not the killing of the unarmed black teenagers? Do the cops’ lives have more value than that of black children?

Third, why is there immediate outrage at the killing of cops but no alarm at the killing of unarmed black kids? Why aren’t the police and government officials conducting grand funeral processions for the dead kids that they conduct for the police killed in the line of duty?

Fourth, why are journalists so keen to take the side of the police and against the question of justice central to the march against the brutal killing of unarmed kids?

Finally, why are cops using military style weapons to target children who may either be unarmed or who may be using toy weapons? (Incidentally, Toys R Us sells toy guns to kids, as part of the weapons culture that is being promoted by the NRA and its supporters). Let us not miss out government’s support of weapons corporations who market weapons globally so we can enjoy a free market of weapons along with beverages.

The cop-killing story became a security blanket for the police who could not find a way to duck the question of why so many black teens across the country are getting killed by police. We need to continue to march and expose the violence that is done by police to the poor and minorities and children and point out that while the killing of cops is tragic, the killing of the unarmed black teens by police is more than tragic: it shows the power of the State trying to eliminate what it deems unworthy. And this undermines not just democracy but the human right to exist—as a dark-colored child or young adult.

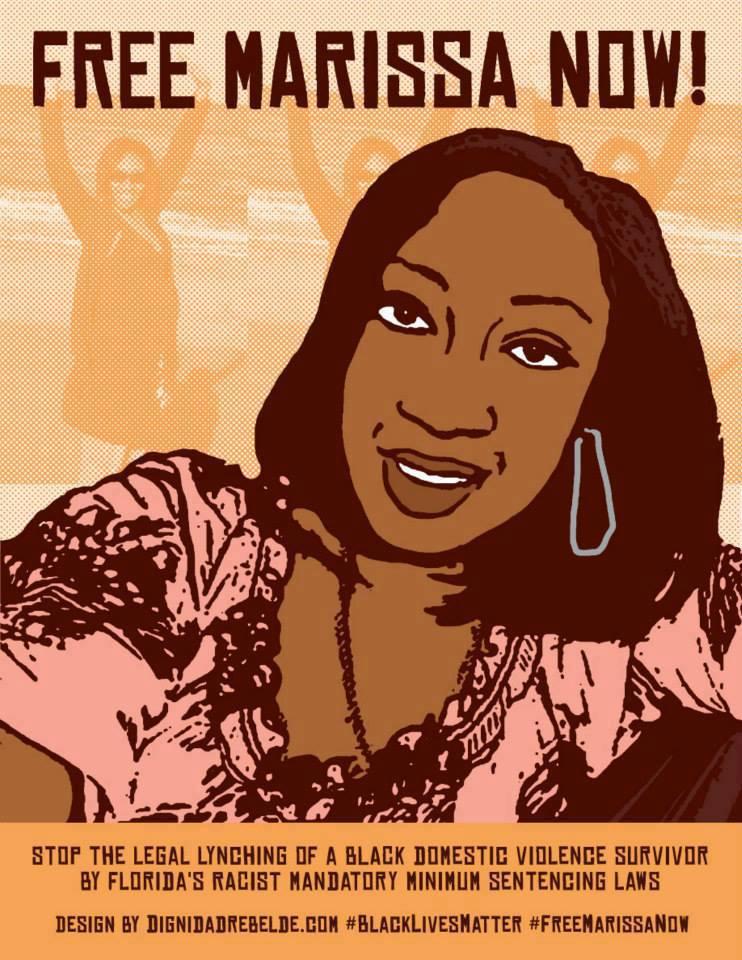

(Photo Credit: http://blacklivesmatter.tumblr.com)