Now is the time to question the terms on which we organise our struggles and wage our battles.

Now is the time to claim our citizenship.

Now is the time to do the work that ensures our lasting freedom.

In this time of “transition” in Zimbabwe, we need to be asking the hard questions of ourselves and each other. We need to organise, hold our structures accountable, make our demands and claim our visions and dreams. Now.

For if not now, when?

As women we have already lived through many empty promises and betrayals by men: be they located within our homes, communities, nationalist movements, newly found states, emerging political parties or that unwieldy, amorphous civil society.

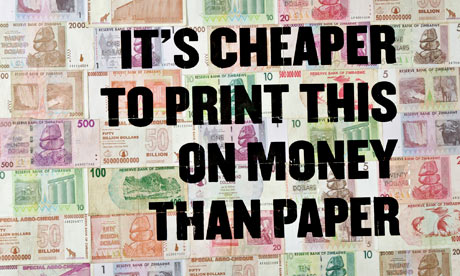

Our lives as women have deteriorated dramatically in the last decade in Zimbabwe, by now we all know why. This deterioration has impacted on how we organise. It has made things harder and more chanllenging. It has eroded our sense of humanity and community. The regime has damaged us all, in one way or another.

But now is the time to be creative in order to do the necessary radical change work. It’s difficult but not impossible. One starting point is articulating the vision of our struggle as women and finding ways to unite around its realisation. This unity has to cut through the partisan politics, the suspicion, the political jockeying, the donor stangle hold and the organisational forms of this time.

For women in Zimbabwe, the horizon of liberation that was intimately connected to our early feminist agenda’s in the 1980’s and 1990’s was gradually left behind, as many of us started operating with a horizon of the law, policy, of governance and gender. Some argue that this was a strategic discursive move but it was at the expense of losing a destabilising power, and women’s organising losing its beating heart.

Feminist consciousness refers to the political consciousness that the gender roles prescribed by societies all over the world for women are rooted in deep prejudices that put the women at social, political and economic disadvantages. It is the desire to counter and stamp out, through collective action and a broad ongoing cultural conversation, such restrictions imposed upon women. Feminist consciousness might have different roots for different women but the vision is the same.

Feminist consciousness challenges many of our deep-held assumptions which, if are not often noticed, is because they are pervasive like gravity. Its complexity helps us understand other related oppressions based on race, class, age, sexual orientation, and disability amongst others.

Gender consciousness is the realization that gender is a socio-cultural construction and society has roles, not rooted in biology, specifically designed for those born into the male and female sexes. But challenging and changing roles is not enough.

Ultimately, gender consciousness and feminist consciousness are related but different concepts. (But I don’t want to get tangled in words. Many women around Zimbabwe are engaging in acts of resistence that are feminist, even though they may have never heard of the word. As long as we share the same commitment to our freedom, to confronting oppression wherever it may be found, let’s move ahead.)

Surely we, including our non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have learnt that gender policies alone ≠ an end to violence, to discrimination, to the bridging of the divides between the public and the private, to a redefinition of our relationships and re-organisation of society where all women can enjoy the fruits of freedom. Almost always legislative, these policies have lacked financial resources and political will. They have not altered the foundations of our oppression. What they have done however, is help to conceal or assuage some of the most detrimental effects of our inequality.

What the so-called gender perspective hides is a total lack of perspective. It’s a convenient myth that a depoliticised gender perspective will lead to equality and overcome sexism.

Now is the time to be critical. To get to the heart of the matter. To think differently. To confront, unpick, challenge patriarchal and capitalist power in order to make lasting change real for women.

What vehicle is going to allow us to do this? If our organizational forms are not going to allow us to get where we want to be, then we must be bold enough to say so. To step out of the shell of the old and into the possibility of the new.

And of course it’s going to be dangerous. You tamper with power, you feel the effects.

I know. This is a rant. It comes from the belief that the gender perspective is not going to get us as far as we need to go.

I don’t have all the answers but my experience tells me that women’s organising in Zimbabwe and the Southern African region needs to politicise.

Politicisation is the (im) pulse running through our organising. “The personal is the political” is a continuous process, a process of transformation which demands time and time again personal engagement, reflection and action.

To put it another way. Opening spaces, to gather what I call feminist forces is a start.

This can be done anywhere and everywhere.

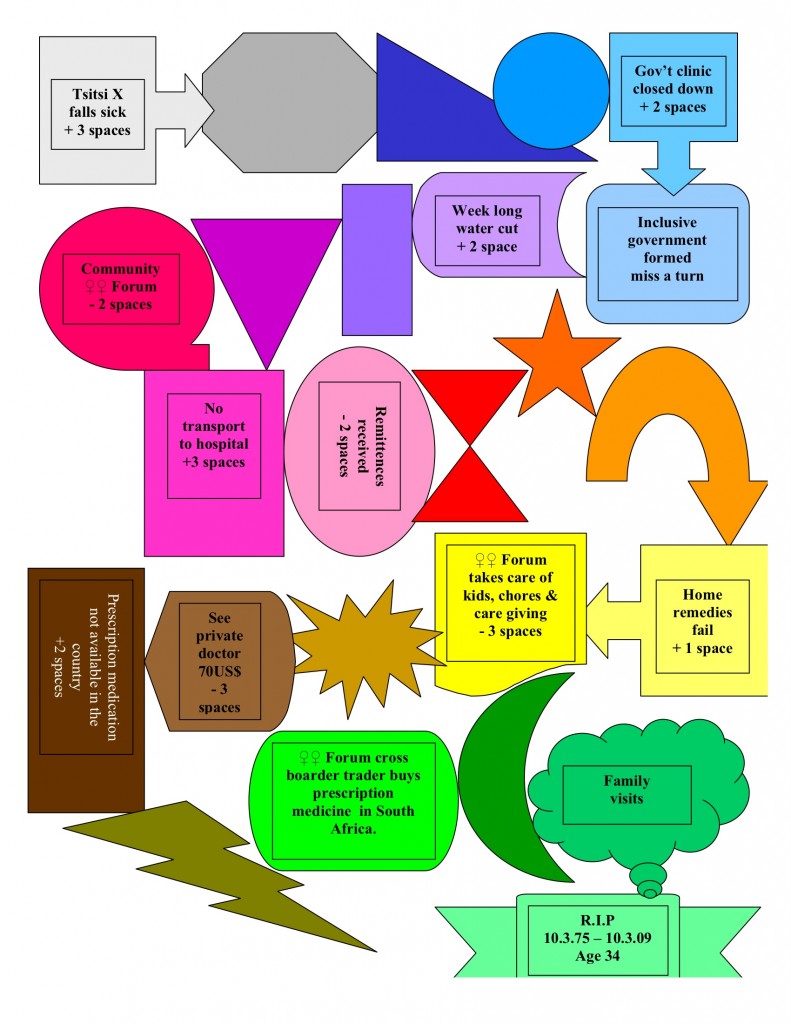

It is literally the process of women getting together, telling each other the stories of the conditions of our lives, and crafting collective visions and practices of resistance out of them. Channelling this into action.

These autonomous dynamic spaces can ground our actions, visions and desires, thereby providing a basis to craft common ground, and create, rather than presume, a basis for collectivity and alliances. This is a start.

The sustainability and radical democracy of this process relies precisely on creating new ways of relating to each other that undermine existing hierarchies and the depoliticisation of power inequalities. Also central to this strategy is the need to practice and nurture alliances between different struggles; the linking of scattered resistances cannot be underestimated.

Much lip-service has been paid to these alliances, often skirting over the hard work they demand in practice. Alliances are about engaging with others, and hence also about dealing with positions invested with power. These alliances are inevitably based on the involvement of our subjectivities; they are about working with differences and working through conflicts. Perhaps they are about love. About humanism. In any case, we cannot render them into abstract models. But we can find words of inspiration for the yearnings that push us to engage in them.

Feminism is about a shared engagement, in anger but more importantly in joy, in laughter, in desire, in solidarity. Right now with constitutionalism looming large in Zimbabwe, what we need to refuse, is performing “the woman’s question” within a larger civic or nationalist movement, that can be raised in certain moments of goodwill, only to be dropped later on when it’s time to get back to “the real business” or to have women’s rights relegated to a toothless policy.

When Adrienne Rich asks women “to see from the centre”, she does so precisely in the context of refusing to be “the woman’s question” or the empty policy. “We are not the ‘woman’s question’ asked by someone else” she comments, “we are the women who ask the questions.”

Women need to ask the questions that disrupt, contaminate and create. However we name them, our struggles are [should be] about nothing less.

(Photo Credit: Research and Advocacy Unit)