In the twenty-first century of neoliberal capitalism, the question – “will I ever be good enough?” – wrings through the minds of millions of women and girls as they stare in the mirror. The answer to this question is no, you will never be good enough in the eyes of neoliberal capitalism.

While this reality may prove depressing at first glance, when one starts to examine the strategic ways that neoliberal capitalism works to undermine individual self-confidence for the sake of profit, one sees the fallacy of such a question from the start. Unlike your mom, who may reassure you that you are “perfect just the way you are,” the money-mongering nature of neoliberal consumerism will always have a problem with who you are, how you look and what choices you make. Don’t feel bad, you’re not alone; no one is good enough.

In We Were Feminists Once: From Riot Grrrl to CoverGirl®, the Buying and Selling of a Political Movement, Andy Zeisler, one of the founding members of the feminist magazine Bitch, works to demystify the aura of neoliberal capitalism and its subsequent effects of feminism. Zeisler describes what many view as “white-feminism” or “feel-good feminism” in this neoliberal age with a new label: marketplace feminism.

Marketplace feminism is a particularly modern form of capitalist feminism that places women’s empowerment in the realm of consumer choice; The freedom of choice is seen as equivalent to gender equity.

Yet the insidious nature of intersecting feminism with marketplace consumerism leaves poor, disabled and minority women of color especially at risk of abjection. Even for those women who can “afford” this type of feminism “the business of marketing and selling to women literally depends on creating and then addressing female insecurity”.

In a system set up for you to constantly fail, we must rid ourselves of self-scrutiny that places the blame on individual selves and instead study the ways in which institutional systems work to create barriers to our feminist realizations.

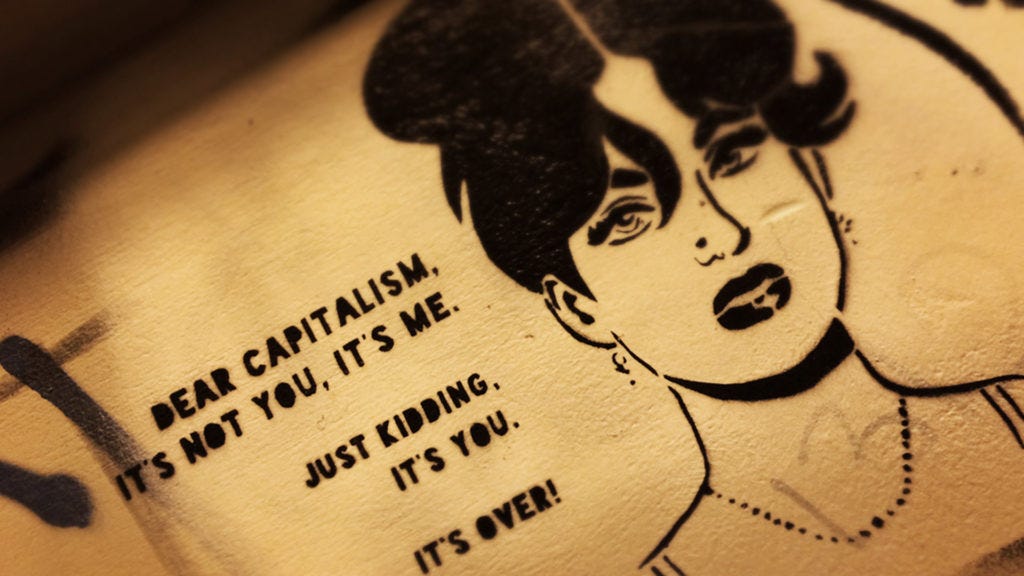

In the eyes of progressively radical, anti-capitalist feminism, you have always been good enough, strong enough and beautiful enough, and you always will be. It’s time to stop internalizing the hateful messages of marketplace feminism that tell you you’ll never be good enough. It’s time to break up with neoliberal capitalism once and for all and start your journey towards radical self-care feminism.

(Image Credit: Medium)