The recent release of Deadly Spin by Wendell Potter, former head of corporate communications for CIGNA, has triggered media interest in trying to explain why there is no sound universal health care system in the United States nor does one appear on the horizon.

In fact, this book could be re-titled “The Confessions of a Public Relations Hit-man.” Potter was, as he writes, a “spinmeister” for the health insurance industry, in particular Humana and CIGNA.

He reveals some of the methods that are commonly used by corporations to “create perceptions without any public disclosure of who is doing the persuading or for what purposes.” He discloses the fundamental tools of the spin-business utilized by industries (health insurance, oil, tobacco, etc.) to manipulate so-called “public opinion” with faulty information, statistics and worse. Words and phrases like “propaganda”, “fear mongering tactics”, and “consumer” appear regularly. This spin-business has found support and sustenance in the absence of political examination of the current US society. Potter is critical of the process but rarely, if ever, critical of the neoliberal thinking that vindicates it. In The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the College de France, 1978 – 1979, Michel Foucault argued “liberalism in America is a whole way of being and thinking.” Potter’s book confirms this critique of `liberalism in America.”

In my attempts to summarize what Deadly Spin exposes, I realized that what it does not expose is equally important. Potter exposes in great detail the technique and the technology of crafting messages made to diminish actual stories of mistreated people to a mere discussion of their economic viability. He also exposes the collusion between corporate power and political power in the United States, showing how corporations get involved in writing bills aimed at controlling their own power.

Potter exposes PR groups, such as APCO, that specialize in “influencing decision-makers and shaping public opinion by crafting compelling messages and recruiting effective allies”. For instance, Michael Moore produced a truthful documentary, Sicko, on the suffering of American citizens who were denied financial coverage of their medical needs. Moore focused on American citizens who had health insurance and how they were vulnerable to the health market emphasizing that access to care was a financial privilege. APCO worked strenously with Potter’s PR team to produce propaganda against Sicko and succeeded in reducing the impact of the film.

A turning point in Potter’s professional life occurred when he came across a RAM (Remote Area Medical) clinic and saw with his own eyes the ways in which people seek care were packed and packaged. Tellingly, the clinic was installed in animal stalls. Nothing prepared him for what he saw.

What the book does not reveal is the link between neoliberal dogma as religion and the reduction of people to consumers of health care. What if Potter had the same revelation in Philadelphia, where he lives, where there is massive poverty, where life expectancy, in some areas and especially in African American communities, is lower than in Bangladesh? What if Potter hadn’t had to travel to the distant rural zones to see the health care situation?

Potter reviews the history of health care reform without revealing the profound effect of racial and social discriminations. His framework remains free enterprise, service, such as there is, remains service to the consumer. He fails to reveal that the neoliberal Public Relations industry has also worked in the worldwide promotion of the same market based health care. Cigna was among the health insurance companies that invested in countries where Structural Adjustment Programs imposed the destruction of public social services, including health care. CIGNA was one of the health insurance companies that grossly benefitted from those deregulations.

Potter also does not address reproductive health and rights, except to note that women’s policies cost more because of pregnancies. In this, he mirrors the decision of the Obama administration to bargain away coverage for abortion and reproductive health as well as immigrants’ health in the passing of an ill conceived and inadequate health care plan.

Nonetheless I appreciate and respect his personal and emotional inquiry. He is right when he says that journalism has become corporately infused. Corporate, and I would add nationalist as well. He gives many examples of PR constructions and distortions of realities meant to keep people in the dark with regard to their health care system, “selling the illusion of coverage,” constructions and distortions that were never denounced or investigated properly by journalists. Those distortions have formed the faith in the power of the neoliberal economy. In the United States, opposition to that faith is subtly silenced. Wendell Potter comes short of acknowledging this relationship. Instead he remains focused on the manipulation of news media, maybe because he started his career in journalism and has now returned to it as a senior fellow on health care at the Center for Media and Democracy.

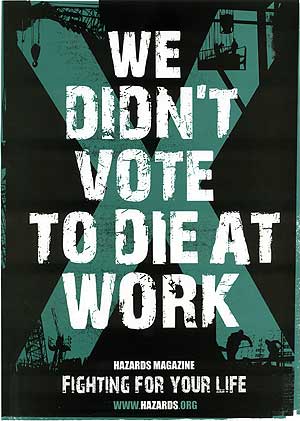

(Photo Credit: PR Watch)