On November 20th 2008, as reported by George Washington University’s student newspaper, the Hatchet, a Latino worker installing windows in a GW residence hall was killed after a fall from the 7th floor. The worker, Rosaulino Montano, worked for Engineered Construction Products, a window subcontractor for primary contractor Clark Construction. His death was featured in one article in the Hatchet, which also reported that the Occupational Safety and Health Association (OSHA) was investigating the incident. The coverage of Montano’s life and his relationship to the university was brief. The Hatchet reported that he lived in Virginia and had several children. The conditions of his work, the events of the accident, and the relationship of the university to Clark Construction or Engineered Construction Products were not examined although the article did note that he was subcontracted to work at GW. There have been no follow up articles.

OSHA reported that sanctions had been imposed on the firm that had hired Montano. The firm “…received one serious violation for violating OSHA’s fall protection standard (1926.501(b)(1)) and a monetary penalty of $2,500. This was the only citation and penalty issued in relation to Mr. Rosaulino Montano, 46, fatal injury. No other employer …was deemed responsible for ensuring safety at the site.”

A brief Hatchet article dutifully marks Montano’s death: “A man fell to his death while installing a window on the seventh floor of the new GW residence hall.” It is reported that he “lost his balance” and “died instantly after he fell out of the window and hit the concrete below.” The article gives a few details about his life. Through a statement by a university spokeswoman, his family is mentioned. After this brief enunciation of concern and regret for loss of life, there is no further curiosity about his life or the manner of his death.

The language of the Hatchet article evokes personal feeling and sympathy or charity (he lived in Woodbridge and had several children) yet the structural contexts of his death aren’t explored. There is little investigation of his employment status, no investigation of what it means to be subcontracted, and no investigation of the routes, economic or otherwise, through which he came to work at the university.

The relationship between Montano and the university community is thin. His life and his death have little content or detail, and no noteworthy or substantial legal, social, economic, or emotional connection to the university community. While there are a few modes of identification, his ties to the university community are tenuous. University business continues, there is no memorial service, there are no statements of regret by university officials, and there is little coverage or desire for information about his life. The conditions of his employment, the conditions of his work, the details of the accident which killed him, and the routes through which he came to work at the university are not visible in accounts of his death.

Short lived regret and sympathy doesn’t pursue what happened to Montano’s family; they are abandoned to depoliticized charitable discourse. It doesn’t pursue the role of the state, the economic arrangement between subcontracted company and the university, the citizen status of the worker, or the relationship between his labor and the life and well-being of the university community.

Giorgio Agamben has something to say about the biopolitics of life and the institutional role of universities in neoliberalism that might help us understand `what happened to Rosaulino Montano”:

If the exception is the structure of sovereignty, the sovereignty is not an exclusively political concept, an exclusively juridical category, a power external to law … or the supreme rule of the juridical order …: it is the originary structure in which law refers to life and includes it in itself by suspending it. . . . (W)e shall give the name ban … to this potentiality … of the law to maintain itself in its own privation, to apply in no longer applying. The relation of exception is a relation of ban. He who has been banned is not, in fact, simply set outside the law and made indifferent to it but rather abandoned by it, that is, exposed and threatened on the threshold in which life and law, outside and inside, become indistinguished. It is literally not possible to say whether the one who has been banned is outside or inside the juridical order. . . . It is in this sense that that paradox of sovereignty can take the form `There is nothing outside the law.’ The originary relation of law to life is not application but Abandonment” (Agamben’s italics).

In a world of abandonment, bodies who do not fit into regimes of life are written out of discourses of mourning, structure of feelings, knowledge systems, and world view of the university. In the rhetoric of abandonment, subcontracted means outside of a collective narrative, recognition of name, traditions, and care of a community, the feelings of community belonging, and the protections of institutions of the state. A public discourse demarcates among kin and those who are not kin, differentiating and marking out, a political space between those who are directly and deeply involved in community and the university (through a relationship to an employer, a relationship to intellectual labor, or a relationship of in loco parentis) from those who are not seen as deeply or directly involved in the work of the university. Public mourning tells us who is valuable and who is not valuable, who is intelligible and not intelligible, which subjects, which bodies, which labor, and which behaviors contribute to domains of value and utility that neoliberal universities produce. Exceptional subjects are included in relationships of ethical responsibility and are mourned. Unexceptional subjects are abandoned to discourse of charity.

The single public text of Mr. Montano’s death reveals a structure of American modernity and liberalism that makes Latino workers disappear. The domesticated immigrant worker in the neoliberal center is identified through markers as father and family man. Work and heterosexuality has the effect of briefly making Montano’s life visible so he can be recognized, his death can be regretted, and responsibility can be directed to the subcontracted company. The events of his life and death are then quickly folded from view. Montano’s death does not become a presence which resonates after a fleeting moment when the events of his death are duly recorded and regret is expressed. He becomes in the structures of feeling of the university a ghostly presence, there but not there, a palimpsest of whom unactualized traces exist.

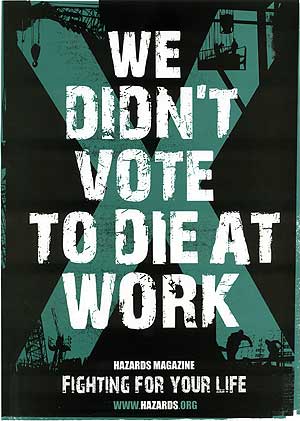

(Image Credit: Union Safety)