I’ve been listening to them talk about 40 years for Lori Loughlin, a person I don’t think I’ve ever spent 10 seconds thinking about before this. I understand the outrage and frustration. Black parents have been thrown in jail for lying about where they lived so their children could attend a better public school. I understand the vulgarity of privilege and have been hurt by it. Often white women who do not acknowledge that privilege have been the very heart of that harm.

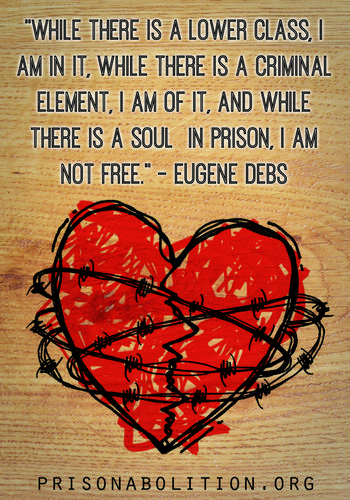

But if I believe in prison abolition, and I do, then I don’t get the option of shifting my philosophy when it suits me. Either I have a principle, or I don’t. Either I believe in transformative justice, which centers the idea that no member of society exists in a vacuum or external to that society and addressing a harm must not be grounded in individual revenge but returning all involved, including the broader community, to whole. Prisons and jails are a failed, lazy response to social disruptions. No matter what the crime. All these people doing time and every harm still stalks us: sexual assault, murder, larceny. Whatever.

I’m interested in working with people who are less about turning up and more about turning in, considering what is needed to have a society where equity and health and compassion and safety and joy are the norm. And yet even from people who say they honor these things, I more hear anger and revenge, emotions I understand well, but ones that I refuse to allow guide any decision I make or position I take.

(Image Credit: Empty Cages Design)