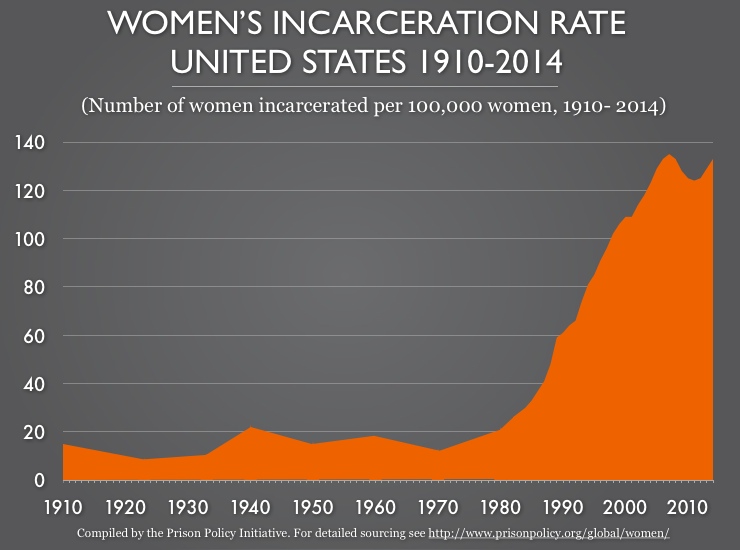

Earlier this month, the U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs Bureau of Justice Statistics released its report, “Prisoners in 2016.” By and large, the numbers are “encouraging” in that prison populations, by and large, are reducing. While certain states buck the trend, overall, thanks to criminal justice reform, fewer people are spending time in prison. That would be good news, except for this: “The number of females sentenced to more than 1 year in state or federal prison increased by 500 from 2015 to 2016”. In a year of generally decreasing prison populations, this exception is noteworthy.

Here are the highlights of “Prisoners in 2016”: “The number of prisoners under state and federal jurisdiction at year-end 2016 (1,505,400) decreased by 21,200 (down more than 1%) from year-end 2015. The federal prison population decreased by 7,300 prisoners from 2015 to 2016 (down almost 4%), accounting for 34% of the total change in the U.S. prison population. The imprisonment rate in the United States decreased 2%, from 459 prisoners per 100,000 U.S. residents of all ages in 2015 to 450 per 100,000 in 2016. State and federal prisons admitted 2,300 fewer prisoners in 2016 than in 2015. The Federal Bureau of Prisons accounted for 96% of the decline in admissions (down 2,200 admissions). The number of prisoners held in private facilities in 2016 (128,300) increased 2% from year-end 2015 (up 2,100). The number of females sentenced to more than 1 year in state or federal prison increased by 500 from 2015 to 2016.” Why are women the exception to the new rule? What’s going on?

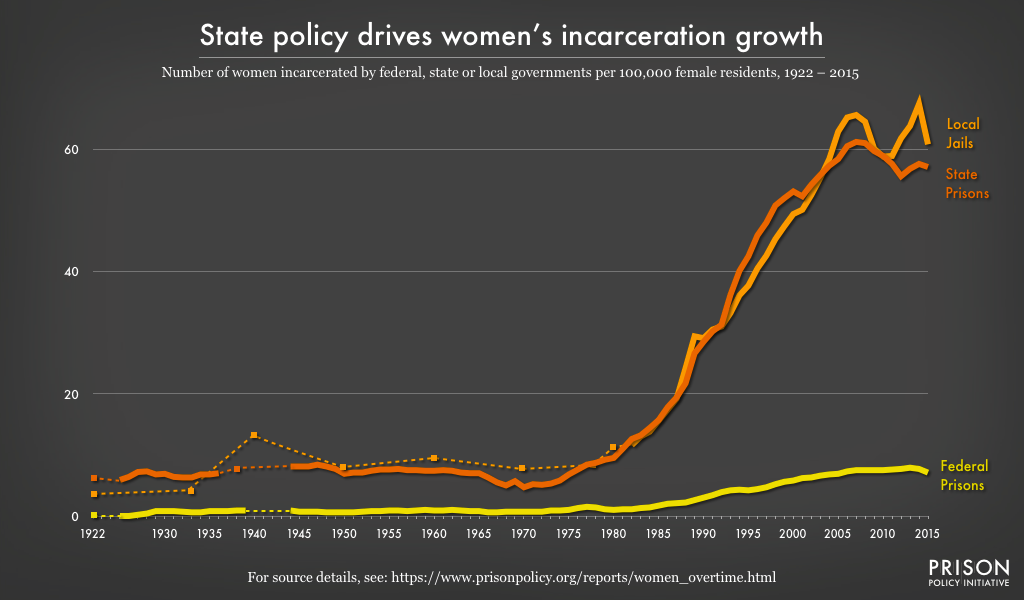

At the end of 2016, women comprised 7% of the total national prison population. From end of 2015 to end of 2016, there were 69 fewer women prisoners, nationwide. In the same period, the number of male prisoners dropped by 21, 137. For women, that’s a .1% reduction, and for men .3%. Twenty states reduced their number of women prisoners while 26 states increased that number, and this is in one year. Kentucky, Washington and Ohio led the pack in increased incarceration of women.

“The imprisonment rate for the U.S. population of all ages was the lowest since 1997 … On December 31, 2016, a total of 1% of adult males living in the United States were serving prison sentences of more than 1 year (1,108 per 100,000 adult male residents), a decrease of 2% from year-end 2015 (1,135 per 100,000). The imprisonment rates for females of all ages and adult females in 2016 were unchanged from year-end 2015 (64 per 100,000 female residents of all ages and 82 per 100,000 adult female residents).”

Once again, Oklahoma had the highest rate of women’s imprisonment: 149 per 100,000 women residents. Kentucky, South Dakota and Idaho follow close behind.

“The imprisonment rate for black females (96 per 100,000 black female residents) was almost double that for white females (49 per 100,000 white female residents). Among females ages 18 to 19, black females were 3.1 times more likely than white females and 2.2 times more likely than Hispanic females to be imprisoned in 2016.”

The war on drugs continues to be a war on women: “A quarter (25%) of females serving time in state prison on December 31, 2015, had been convicted of a drug offense, compared to 14% of males … More than half (56% or 6,300) of female federal prisoners were serving sentences for a drug offense, compared to 47% of males (75,600).”

While rates of incarceration and raw numbers of incarcerated people decline, rates of incarceration for women increase and raw numbers of women sentenced to more than a year increase. That is not an oversight. That is public policy. The war on women, waged through police, courts, and prison, continues. If the report were to include immigrant detention, the profile would be that much clearer. It’s time to stop the war on women, to pay greater attention to the reasons that the State targets women for imprisonment. It’s time to end the national witch hunt.

(Image Credit: Prison Policy Initiative)