We live in an age of news desertification. Today, May 3, is World Press Freedom Day, and much of the discussion of press freedom centers, rightly, on censorship, and on the intimidation, brutalization and imprisonment of reporters. At the same time, and especially in the United States, “news deserts” are popping up in fairly predictable communities: rural areas and urban minority neighborhoods: “Minority communities in big cities tend to be the most arid news deserts of all.” News deserts are places in which people can no longer get the local news, and it’s the no longer that matters here. News deserts are places that had local community newspapers, usually for generations that either failed or, as with the vast majority, were bought out by corporate interests and then dumped or `re-tooled’ out of their community base. While the news air is indeed very dry in urban minority communities, the epicenter of news desertification across the United States is the prison, and the dead center of that map is the women’s prison.

Prison journalism has a long and storied record in the United States. In 1887, a group of prisoners in the Stillwater Prison, in Minnesota, pooled money and energies and founded The Prison Mirror. Today, The Prison Mirror is the longest running jailhouse newspaper in the United States. Today, The Prison Mirror, The Angolite, started in 1976, and the San Quentin News, revived in 2008 after 26 years of silence, are the only three prisoner-run publications that do serious and investigative reporting on criminal justice and injustice. But the real story is the rise and fall of prison newspapers.

The Prison Mirror was wildly successful from the beginning, so much so that prison newspapers, newsletters and news magazines started popping all over the country. By the early 1960s, there were prison reporters in almost every state. From 1965 to 1990, there was an active Penal Press Awards, with real competition among real prison house journalists. Then the 1990s happened. A predictable component of mass incarceration’s austerity budgets was the elimination of educational and cultural programs, included in which was the programmatic disappearance of jailhouse news venues. More prisoners, more isolation, more self harm and suicide, and more silence. Mass incarceration = news desertification.

Today, there are very few prisoner-run news outlets, and that’s a shame. These projects did more than “help” prisoners, although prisoners certainly benefited from them. Check out The Prison Mirror, The Angolite, or the San Quentin News and you’ll see hard hitting and urgently useful news reporting.

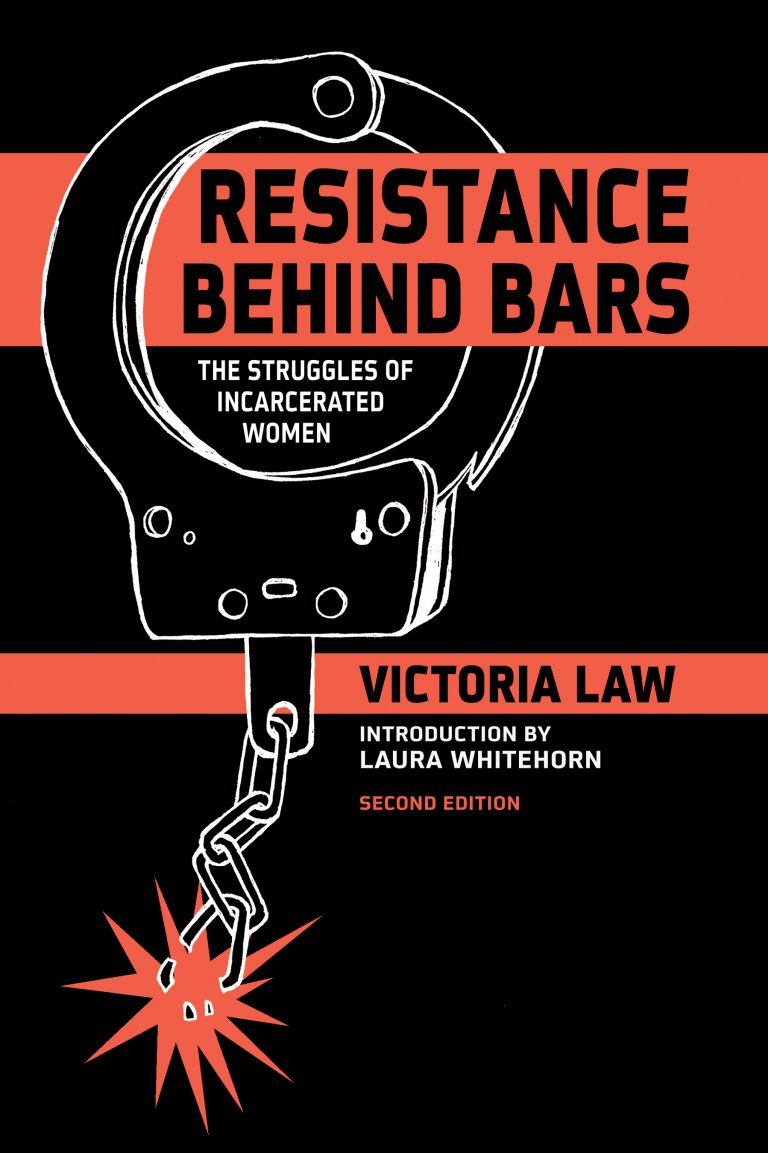

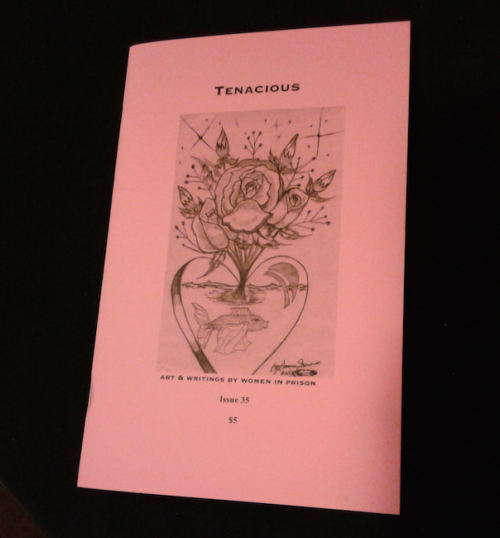

Where are the women? Here, there and everywhere. Short-lived newspapers emerge from a journalism course, and women prisoners produce newsletters, like Through the Looking Glass, published by women prisoners at the Purdy Correctional Treatment Center, outside Seattle, Washington, between 1976 and 1987. From 2002 to 2006, women prisoners at the Edna Mahan Correctional Facility for Women in New Jersey published a monthly magazine, Perceptions. In 2003, women prisoners in Oregon approached Vikki Law to help them publish their voices and visions, and so was launched Tenacious, a zine of art and writings by women incarcerated across the United States. The most recent issue, Tenacious 35, was published in December 2015.

None of these has received the kind of support, institutional and cultural, given to similar projects in men’s prisons. The Prison Mirror, The Angolite, and the San Quentin News are great examples of prisoner run news media, and they are great examples of the resources needed to sustain such projects, from the warden and staff to time and space to training to encouragement, from within and without. It’s way past time to recognize AND support women prison journalists. Prison doesn’t have to be a news desert, and women’s prisons don’t have to be shrouded in silence.

(Image Credit: California Coalition for Women Prisoners) (Photo Credit: POC Zine Project)