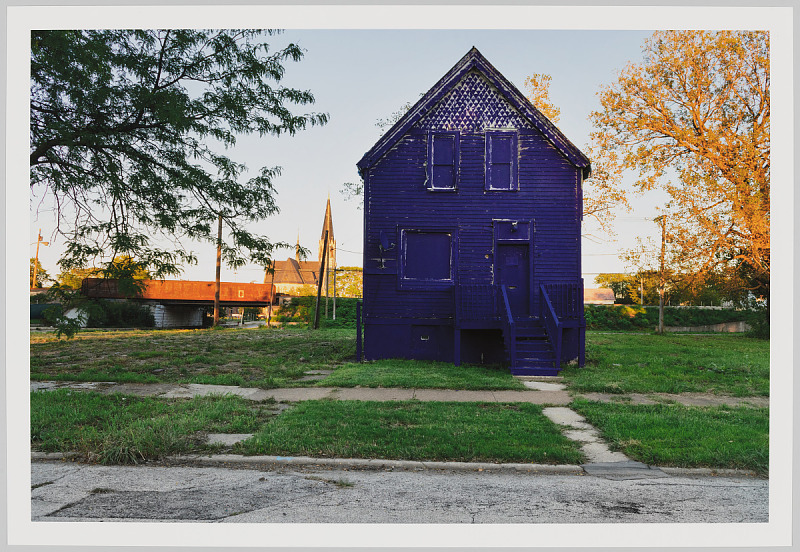

The population of Kampala is currently estimated at 4,051,000. In 2014, it was 2,453,000. In twenty years, the city has grown 165%. The city has one garbage dump, the Kiteezi Landfill. It is the largest garbage dump in Uganda and in all of East Africa. It is located in a densely populated, low-income area of Kampala. The Kiteezi Landfill was opened in 1996 and was meant to run until 1996. In 2021, Kampala Capital City Authority-KCCA “began” the process of closing Kiteezi Landfill with a study to inform safe closure. It stayed open. In June 2024, the KCCA Directorate of Public Health and Environment received a report stating that the conditions at the landfill were dangerous and life-threatening: “Significant cracks and waste slides were observed in the north-eastern section of the site, blocking the main drainage channel and causing leachate to flood nearby areas, including a neighborhood farm.Dr. Daniel Ayen Okello, Director of Public Health and Environment at KCCA, noted that the Kiteezi Landfill, a critical waste disposal site for Kampala, is facing severe operational challenges. The landfill, which has been operating beyond its capacity, has developed hazardous conditions threatening both waste management efficiency and community safety.” There was no response. On Friday, August 9, 2024, the Kiteezi Landfill collapsed. As of the latest count, 30 people were killed. That number is expected to rise. Numerous houses adjoining the landfill were submerged in trash. The landslide occurred late at night. Hundreds are missing, hundreds have been displaced. Yesterday, the government announced it was “moving to decommission the Kiteezi Landfill.” Case closed.

Of course, this was a tragedy foretold. It’s also a tragedy that the world noted, for a blip, and then will move on. Remember the Koshe Landfill in Addis Ababa? Remember the Hulene Landfill in Maputo? “The Kiteezi landfill is on a steep slope in an impoverished part of the city. Women and children who scavenge plastic waste for income frequently gather there, and some homes have been built close to the landfill.” Who will remember; who will care?

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Photo Credit: Travel Uganda)