The World Bank is still bad for women, children, men, and all living creatures. While not surprising news, it is the result of a mammoth research project carried on by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and their partners. Journalists pored through more than 6000 World Bank documents and interviewed past and current World Bank employees and government officials involved in World Bank funded projects. They found that, in the past decade, an investment of over 60 billion dollars directly fueled the loss of land and livelihood for 3.4 million slum dwellers, farmers, and villagers. That’s a pretty impressive rate of non-return, all in the name of modernization, villagization, electrification, and, of course, empowerment. Along with sowing displacement and devastation, the World Bank has also invested heavily in fossil-based fuels. All of this is in violation of its own rules.

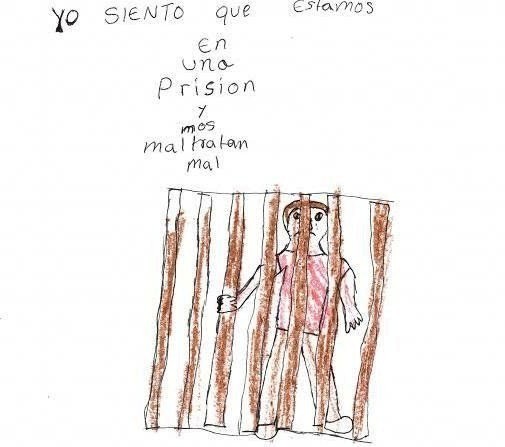

Women are at the core of this narrative, and at every stage. There’s Gladys Chepkemoi and Paulina Sanyaga, indigenous Sengwer who lost their homes and houses, livestock and livelihoods, and almost lost their lives to a World Bank-financed forest conservation program in western Kenya’s Cherangani Hills. In 2013, Bimbo Omowole Osobe, a resident of Badia East, a slum in Lagos, lost nearly everything to a World Bank funded urban renewal zone. Osobe was one of thousands who suffered “involuntary resettlement” when Badia East was razed in no time flat. Today, she’s an organizes with Justice and Empowerment Initiatives, a group of slum dwellers fighting mass evictions. Aduma Omot lost everything in the villagization program in Ethiopia, a World Bank funded campaign that has displaced and demeaned untold Anuak women in the state of Gambella. In the highlands of Peru, Elvira Flores watched as her entire herd of sheep suddenly died, thanks to the cyanide that pours out of the World Bank funded Yanachocha Gold mine, the same mine that Maxima Acuña de Chaupe and her family have battled.

The people at ICIJ promise further reports from India, Honduras, and Kosovo. While the vast majority of the 3.4 million people physically or economically displaced by World Bank-backed projects live in Africa or Asia, no continent goes untouched. Here’s the tally of the evicted, in a mere decade: Asia: 2,897,872 people; Africa: 417,363 people; South America: 26,262 people; Europe: 5,524 people; Oceania: 2,483 people; North America: 855 people; and Island States: 90 people. The national leaders of the pack are, in descending order: Vietnam, China, India, Ethiopia, and Bangladesh. It’s one giant global round of hunger games, brought to you by the World Bank.

None of this is new. In 2011, Gender Action and Friends of the Earth reported on the gendered broken promises of the World Bank financed Chad-Cameroon Oil Pipeline and West African Gas Pipelines: “The pipelines increased women’s poverty and dependence on men; caused ecological degradation that destroyed women’s livelihoods; discriminated against women in employment and compensation; excluded women in consultation processes; and led to increased prostitution … Women in developing countries have paid too high a price.” The bill is too damn high.

In 2006, Gender Action and the CEE Bankwatch Network found that women suffered directly from World Bank funded oil pipeline projects in Azerbaijan, Georgia and Sakhalin: “Increased poverty, hindered access to subsistence resources, increased occurrence of still births, prostitution, HIV/AIDS and other diseases in local communities.”

There’s the impact on women of ignoring, or refusing to consider, unpaid care work in Malawi, Mali, Niger, and Rwanda, and the catastrophic impacts on women of World Bank funded austerity programs in Greece. And the list goes on.

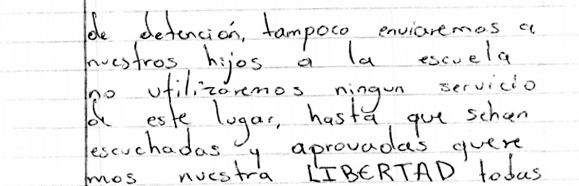

So, what is to be done? Past experience suggests that the World Bank is too big to jail. How about beginning by challenging and changing the development paradigms and projects on the ground? No development that begins from outside. Absolutely no development that isn’t run by local women and other vulnerable sectors. While the World Bank refuses to forgive debts, globally women are forced to forgive the World Bank’s extraordinary debt each and every second of each and every day. This must end. Stop all mass evictions. Start listening to the women, all over the world, who say, “We need our voices heard.”

(Photo credit: El Pais / SERAC)

_LRG.jpg)