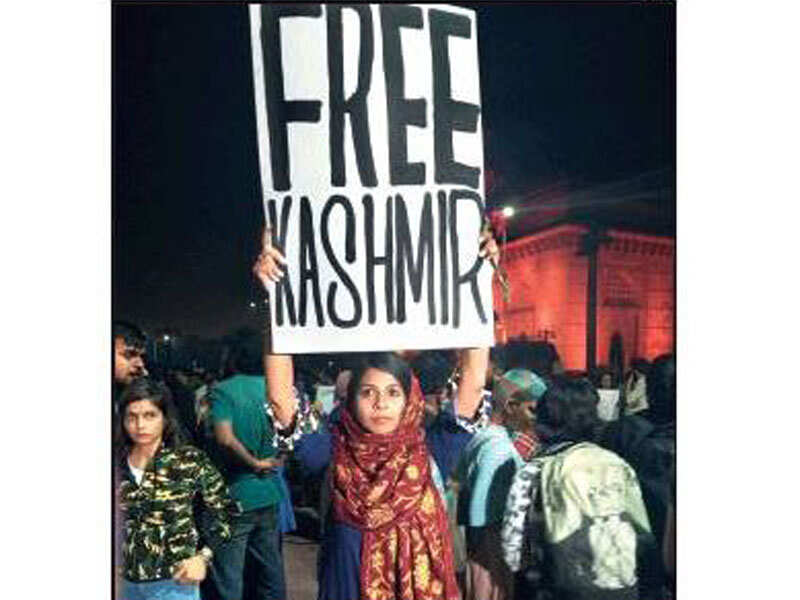

After a year of protests by farmers in India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has announced that he would repeal the infamous agricultural laws, which had sparked the protests last November.

Most of the farmers in the demonstrations hailed from the northern Punjab and Haryana states-two of the biggest agricultural producers in the country. The farmers raised major concerns that the law-which was signed September of 2021, introduced market reforms to the farming sector, a move that the smallholder farmers argued would favor large corporate farms, devastate the earnings of many of the poorer farmers, and leave those who, “hold small plots of land behind as big corporations win out.”

The fear is that the new legislation will leave the farmers poorer, at a time where Modi had attempted to reinvent India as a “hub for global corporations.” The bill is also not clear on whether the government will continue to guarantee prices for certain essential crops, which would leave small farmers open to large agrobusiness competition; farmers had already voiced concerns as the government attempted to liberalize the farming markets and move away from a system of farmers selling only to a government-sanctioned marketplace, which would have left them at the mercy of corporations without any legal obligation to pay them the guaranteed price. Clauses in the legislation almost guaranteed that the farmers were on their own-including one that would have prevented them from taking contract disputes to court, thus having no means of redress apart from bureaucrats.

The subsequent protest had been the biggest since Modi claimed power in 2014 and erupted at a time of economy and social insecurity, with laws that were deemed discriminatory and a botched COVID-19 response. Dozens of farmers have died during the process, one from the police during a demonstration in January when protestors stormed the Red Fort in the capital’s center, and others from either suicide, bad weather from the demonstrations, or COVID-19.

While Modi has promised a repeal of the law, farmers and their unions are not backing down. Samyukt Kisan Morcha, the group of farm unions organizing the protests, said, “It welcomed the government’s announcement but that the protests would continue until the government recommits to the system of guaranteed prices. The protesters had long rejected a government offer to suspend the laws for 18 months.”

The announcement came on the day of the Guru Purab festival, where Sikhs celebrate their founder Guru Nanak’s birthday. The laws have been particularly alienating to the Sikh community and come after Modi attempted to discredit the protesters as being motivated by religious nationalism. The move to repeal the law on Guru Purab, amidst an important election cycle, while most definitely Modi’s government attempting to do damage control, is nonetheless a decisive win for poor farmers whose annual income is 20,000 rupees or $271.

(By Nichole Smith)

(Photo Credit: Altaf Qadri / AP)