Mitochondrial DNA

Mama told me a story

She said:

You are an ocean and I am a river that feeds you and makes you grow.

If I’m an ocean now; then what will I be when I grow up, I asked?

That’s easy, she said, you’ll be a river that will feed an ocean just as I do.

Choose those that choose you.

Not every eye can see your coat of many colors

Nor can every ear hear your plaintive cries desiring belonging

Not all fingers can touch the wounded places and the scars

Nor offer the healing touch of consolation.

Not all skin folks are kin folks

And strong enemies contribute to ones growth, too.

Rivers lose their identities once they reach oceans.

Lose their identities

And their contradictions.

Who is my mother and father asks the ocean?

Child of many streams

And many rainstorms

Where is your home

And where will you lay your head?

What floodgates open because of intrepid questioning?

And, what Jerichonian walls crumble because of courageously blown conch shell horns?

Funeral Pyres blaze in India

Telling two stories

One ancient

And one new

Tell me who I am as I inhale deeply

As the dust of the dead mingles and enters my nostrils

reminding me that I am a sleeping god.

Pandora’s curiosity brought forth both plague and hope.

Who is my family in all of this?

Like calls to like; but, can that call be answered?

All of this is mission; but, can it be accomplished?

My brothers and sisters have many names.

They ask questions as I do

And are not afraid of the answers that they receive.

By their curiosity my Family of Choice is known.

In Tibet they are called Vidyādhara because they want to know

And knowledge is their seat.

Among the Lakota they are called Heyoka — contrarians for whom night is day and day is night

And, Reality is only just when and if it can be questioned.

In India they are called Brahmins because they seek the truth.

This cannot be achieved merely through bloodlines and birth within a family.

Among Yoruba Orishas, my family calls on Shango

And the Wise Women in my family venerate Yemaya.

American Griots,

Fearlessly tell your stories and sing your songs

And teach the children to sing, too.

Sing the songs that Grandma sang in the kitchen

Or as she danced on the laundry with her blessed feet.

Sing work songs and war songs

That helped men survive chain gangs

And oppressive assembly lines.

Sing bawdy songs and love songs

That foment perilous rendezvous.

Sing new songs of Hope and learn to call on The Mothers once again.

How many more Mothers of Exiles can be named

In this melting pot called America?

That hasn’t yet finished melting

Not even close.

But the Gods came here to these shores with the people who brought them

Listen for the answers that they whisper

Even though we vaguely call upon them

With dimly remembered prayers.

Let your peace fall upon all of those who will listen to you and receive you

But if they shun you

Shake off the dust of your sandal on their threshhold

As a testament against them and their house

Then walk on.

All it takes to make stone soup is

A pot

A stone

a story

And the willingness of Families of Choice to bring the rest of the ingredients.

All seasonings and flavors blend in a stew.

And all oceans eventually become rivers that feed other oceans

Losing both their identity and their contradictions

I am just a ghost driving a mitochondrial DNA machine made of:

Blood

Fat

Bone

Marrow

Tissue

Ovum

And Sperm

Why am I even afraid?

(By Heidi Lindemann and Michael Perry)

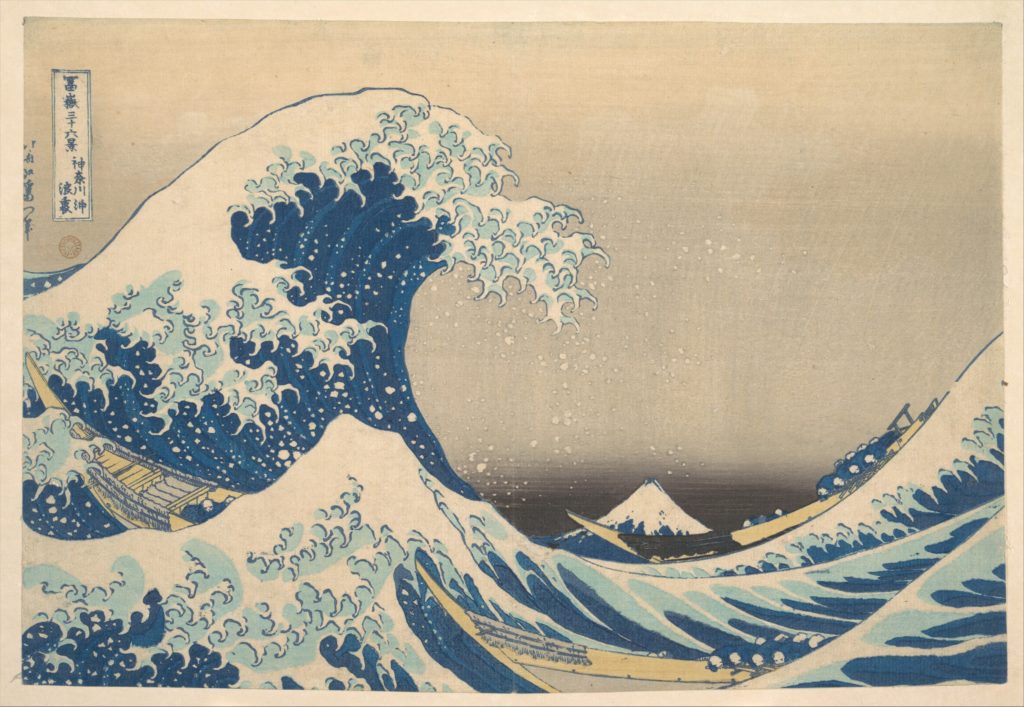

(Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum)