In the spirit of Holy Week, the mothers of Karnes Immigration Detention Center, in south Texas, are on work and hunger strike. With their bodies, they are asserting their humanity, sisterhood, dignity, and, as so often, with their bodies they are protecting their children. This is the highway to hell we have constructed over the last few decades. Women and children fleeing violence, pleading for help and haven, are criminalized, vilified, and thrown into prisons. The site-specific irony, and tragedy, is that when Karnes was opened in 2012 the Obama administration hailed it as a model for more humane and less penal treatment of immigrants. All hail the new model.

Karnes is so great that when Victoria Rossi, a paralegal, recently described the conditions therein, she was rewarded by being barred from the establishment. The conditions at Karnes are neither new nor unknown. Last year, the American Civil Liberties Union, the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund and others wrote letters, filed complaints, and sued the Federal government because of the conditions at Karnes. MALDEF documented numerous cases of sexual abuse, extortion and harassment of women. The ACLU cited numerous women, who fled domestic violence at home, only to be locked behind bars in Texas.

People heard. Individuals and communities heard. The State shrugged.

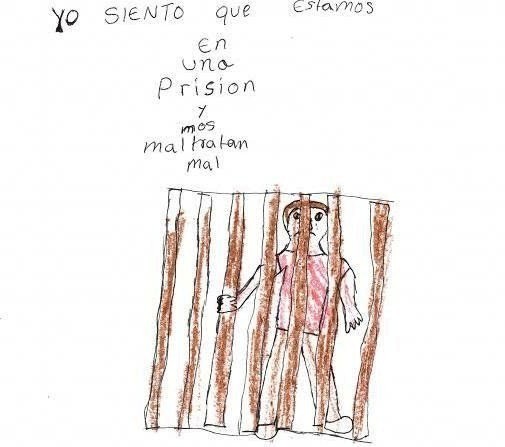

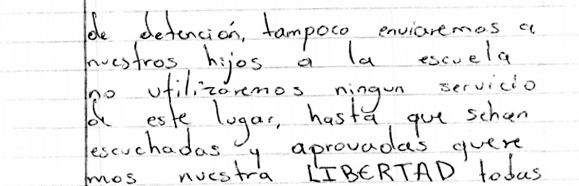

And so now the women of Karnes are on hunger and work strike, and that is the story, the miracle of humanity. The mothers of Karnes have written a letter, which reads, in part: “In the name of the mothers, residents of the Center for Detentions in Karnes City, we are writing this petition whereby we ask to be set free with our children. There are mothers here who have been locked in this place for as long as 10 months … We have come to this country, with our children, seeking refugee status and we are being treated like delinquents. We are not delinquents nor do we pose any threat to this country. You should know that this is only the beginning and we will not stop until we achieve our objectives. This strike will continue until every one of us is freed. The conditions, in which our children find themselves, are not good. Our children are not eating well and every day they are losing weight. Their health is deteriorating. We know that any mother would do what we are doing for their children. We deserve to be treated with some dignity and that our rights, to the immigration process, be respected.”

You can support the women by signing their petition to ICE director Sarah Saldaña and ICE San Antonio Office Director Norma Lacy. The demand is pretty straightforward: “Grant discretion & RELEASE the children and mothers detained at Karnes!“

Once, providing asylum to those who needed it was considered a sacred act. In the Book of Numbers, God ordered Moses to create “cities of refuge” or “cities of asylum,” for those fleeing unjust punishment. Women, like Ruth and Naomi, strangers in a strange land, could hope to take refuge in the shadow of the wings of a divinity embodied in human acts of mutual recognition. Today, the descendants of Ruth and Naomi live in Karnes, and they demand their freedom to be human beings: “We will keep refusing food until our demands for release are recognized. We will fight until we are granted our liberty. We’re tired of the treatment we’re receiving here. Our children are all losing weight because they’ve lost their appetites. It’s like we’re living in a jail.” Today, Ruth is named Kenia, and she’s 26 and from Honduras.

(Lead image credit: The Rag Blog) (Letter image: Colorlines)