Death, be not proud, though some have called thee

Mighty and dreadful, for thou are not so;

For those whom thou think’st thou dost overthrow

Die not, poor Death, nor yet canst thou kill me.

John Donne, “Death Be Not Proud”

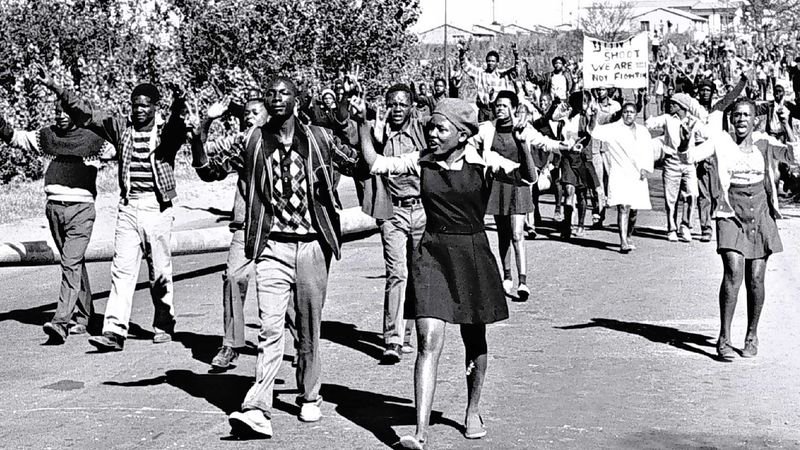

Sikhosiphi Bazooka Rhadebe, chairman of the Amadiba Crisis Committee, on the Wild Coast of South Africa, was brutally assassinated last night, and so joins Berta Cáceres and Nelson Garcia, and who knows how many others martyred in this month alone? The Amadiba Crisis Committee, largely made up of women, has been struggling to stop mining in Xolobeni, the Mgungundlovu area of Amadiba Tribal Administrative Area in Pondoland, and to continue a program of people-driven, sustainable development. The response has been a reign of fear and intimidation. Repeatedly, the women and men of Xolobeni have said, We are ready to die for this land. Last night, Sikhosiphi Bazooka Rhadebe was murdered, or better executed. It did not come as a surprise. As Nonhle Mbuthuma explained, for the last year, the police have waged a campaign of intimidation, and, when called on to stop the violence, “There has been nothing.”

Men come with guns and women respond, “My tears won’t fall on the ground for nothing. You can bring your machine guns. I am prepared to die for my land; I am not going anywhere.”

The crisis is not mining. The crisis is violence: violence against nature, women, the community, and democracy. Nonhle Mbuthuma has grown up in the struggle for a decent and better life, and for a State where one can’t say, “There’s too much `democracy’ in this democracy”; and Sikhosiphi Bazooka Rhadebe is dead, having striven to make that democracy-to-come a reality today.

It is not a reality today. Reality today is State violence, from Honduras to South Africa and beyond. As Berta Cáceres exhorted, “We must take action!” We must turn the swords of murder into the ploughshares of sustenance. Berta Cáceres, Nelson Garcia and Sikhosiphi Bazooka Rhadebe will not rise out of the earth, no matter how fervently some might pray, but their dream, their collective unified dream, cannot be killed. We must take action!

(Photo Credit: United Front)