Samukelisiwe Mlilo

Samukelisiwe Mlilo and lawyers from the Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights went to court this week to challenge the constitutionality of a Zimbabwean law that criminalizes “HIV transmission.” The story of Samukelisiwe Mlilo is the story of one woman in one household, and it is the story of criminalization of HIV transmission as part of a global assault on women.

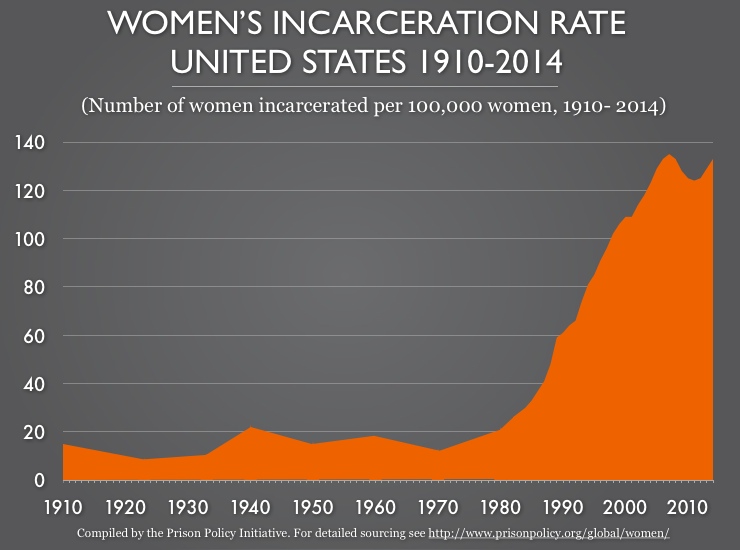

On every continent, countries have passed laws that criminalize something called intentional HIV transmission. Each time, the law is draped in the language of protection: of society, of women, of `us’ from the monstrous `them.’ The specter that haunts these laws, however, is not predatory monsters, but rather women.

In Zimbabwe, the law that adjudicates “deliberate transmission of HIV” is Section 79 of the Criminal Law Code: “Deliberate transmission of HIV: Any person who, knowing that he or she is infected with HIV; or realising that there is a real risk or possibility that he or she is infected with HIV; intentionally does anything or permits the doing of anything which he or she knows will infect, or does anything which he or she realises involves a real risk or possibility of infecting another person with HIV, shall be guilty of deliberate transmission of HIV, whether or not he or she is married to that other person, and shall be liable to imprisonment for a period not exceeding twenty years.”

This law sits at the intersection of legal arguments, made last week by the Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights, which point to the unconstitutional vagueness of the language of the law; and women’s lived lives, call it the existential tragedy, which is the story of Samukelisiwe Mlilo. Both the Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights and Samukelisiwe Mlilo argue that the law targets women.

Samukelisiwe Mlilo is 36 years old, a mother of three young children, HIV positive, separated from her husband. In August 2009, Mlilo was pregnant with her second child. She went in for prenatal care, and was found to be HIV positive. She struggled to accept her status, and then, fairly quickly, informed her then-husband. At first, things were ok, but soon the two began fighting. According to Samukelisiwe Mlilo, her husband became violent and physically abusive, but he did stick around and help with childcare, after the second child was born. Finally, in 2010, Samukelisiwe Mlilo went to the police, reported her husband’s abuse, got a restraining order, and they formally separated. Her husband was given visitation rights, and so the fighting and abuse continued. When the two separated, Samukelisiwe Mlilo was three month pregnant, which neither she nor her husband knew. He rejected the child, who was born June 2011. Then, out of the blue:

“One day I was summoned to Entumbane police station to answer charges of deliberately and knowingly infecting him with the HIV virus. I informed the policeman that I disclosed my HIV status to this man who accepted it. Now he is lying saying I didn’t disclose my status to him because we had separated. Honestly I did not know what was happening … I had no one to ask to take care of my children. I stayed alone with my children and the child minder. There was no one to take care of my children … It was difficult, especially when the case was covered in the newspapers. I could not work. I could not face my co-workers. I requested for emergency leave, which was denied. I was forced to interact with people, despite the difficult situation I was in. People were calling me names. It was indeed a difficult time. At that time I was also supposed to continue looking after my children. I had to face people and attend to phone calls from relatives, who had seen the story in the paper. If I had not been a woman, I would not have faced any of these challenges.”

Due to requirements women face when accessing antenatal care, women more regularly learn their HIV status. Thus, the burden of informing has been placed largely on women, and women then have to do the calculus. Around the world, women who inform their partner that they are HIV positive often face violence and death, expulsion, homelessness, stigma, and poverty. Additionally, they are more often than not left to care for the children on their own in a hostile environment.

Criminalization adds two elements to this toxic brew. First, it allows for the violation of the right to privacy and confidentiality. We should not know Samukelisiwe Mlilo’s name, but `thanks’ to the criminalization laws, we do. The second toxic element is prison. While prison for any woman is a terrible thing, her imprisonment is a living death sentence for her children.

Last week, the Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights released a video telling the story of Samukelisiwe Mlilo, and of women around the world. It concludes: “Say NO to criminalisation of HIV. Criminalisation harms women.” In the words of Samukelisiwe Mlilo, “If I had not been a woman …” Being a woman is not and cannot become a crime.

(Video Credit: YouTube / Zimbabwe Lawyers Committee for Human Rights / HIV Justice Network)