This week, Utah’s Legislative Auditor General submitted a performance of health care in Utah’s state prisons. The Auditor found “systemic deficiencies”: “The lack of follow-up and patient monitoring is a systemic concern that extends beyond the Covid pandemic.” Reading this report, it’s a wonder that anyone survives Utah’s prisons. In fact, they don’t. According to a report earlier this year, “people in Utah’s prisons were five times more likely to die of COVID-19 than the average Utahn.” While five times more likely is high, it’s not much higher than prisons across the United States, boasting four times the infection rate of the country’s general population. And then there’s FCI Waseca, a low-security Federal prison for women, located in Waseca, Minnesota. FCI Waseca houses 756 women, of whom, according to the latest number from the Federal Bureau of Prisons, 132 are currently infected with Covid. That’s the most of any Federal prison. The next in line is a Federal prison in Pollock, Louisiana, with 30 incarcerated people infected. FCI Pollock houses 1,556 incarcerated people. Less than 2% of FCI Pollock is infected with Covid; 17% of those in Waseca are Covid-infected. Waseca accounts for 47% of all infected incarcerated people in the U.S. Federal prison system. These numbers provide the profile for “low security”.

At 199 Covid infections per 100,000, Waseca County has the highest rate of Covid infection of any county in the United States. Minnesota state prisons house 7,323 incarcerated people. Of that population, 95 are currently Covid infected, far less than 1%, although one prison, MCF Lino Lakes, 70 of its 911 incarcerated residents are Covid infected, a little under 8%.

Since the start of the pandemic, around 450 incarcerated women have tested positive for Covid. On Wednesday, December 8, the ACLU sued both FCI Waseca’s warden and the Director of the U.S. Bureau of Federal Prisons, claiming that the prison failed to take measures to contain Covid. FCI Waseca failed to release women with medical conditions to home confinement and failed to reduce the prison population sufficient for any kind of social distancing. That was no failure, that was refusal.

FCI Waseca is organized as dormitories with bunk beds kept close together. Everything is done in fairly tight common, social spaces. None of that was changed in any way in response to Covid. In August, a group of around 40 women was transferred from a facility in Oklahoma, a facility which was reporting Covid infections. The women from Oklahoma were placed in bunk beds in a unit with other bunk bedded women right next to them. Within weeks, most of the women in that unit tested positive for Covid.

What is there to say? FCI Waseca refused to address Covid, refused to respect women’s Constitutional rights to safety, refused to imagine an alternative to packing them in until it’s time to go. “Low security” should not be a death sentence nor should it mean being endangered. In fact, nothing should be a death sentence, but there we are. Two years into a pandemic, and we continue to cling desperately to the charnel house as the only way. If nothing else, by this point, perhaps people will stop saying, “The prison failed” to do this or that. There was no failure, there was only refusal, in broad daylight for all to see and without any remorse whatsoever.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

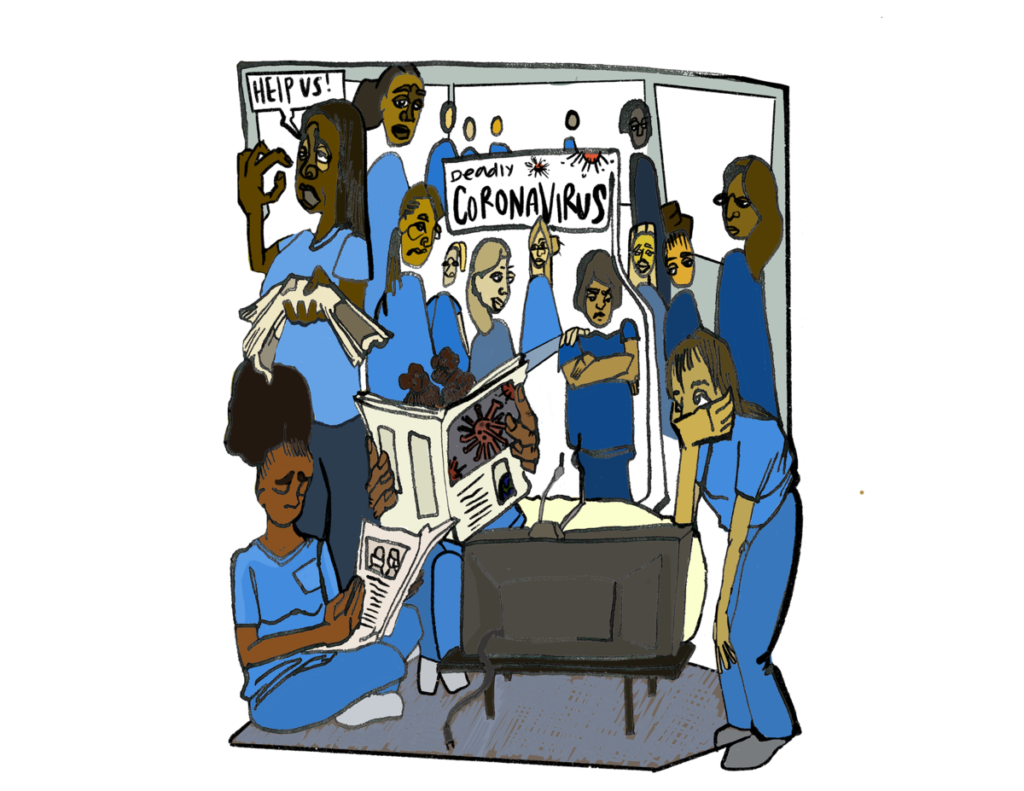

(Image Credit: Kayla Salisbury / The Marshall Project)