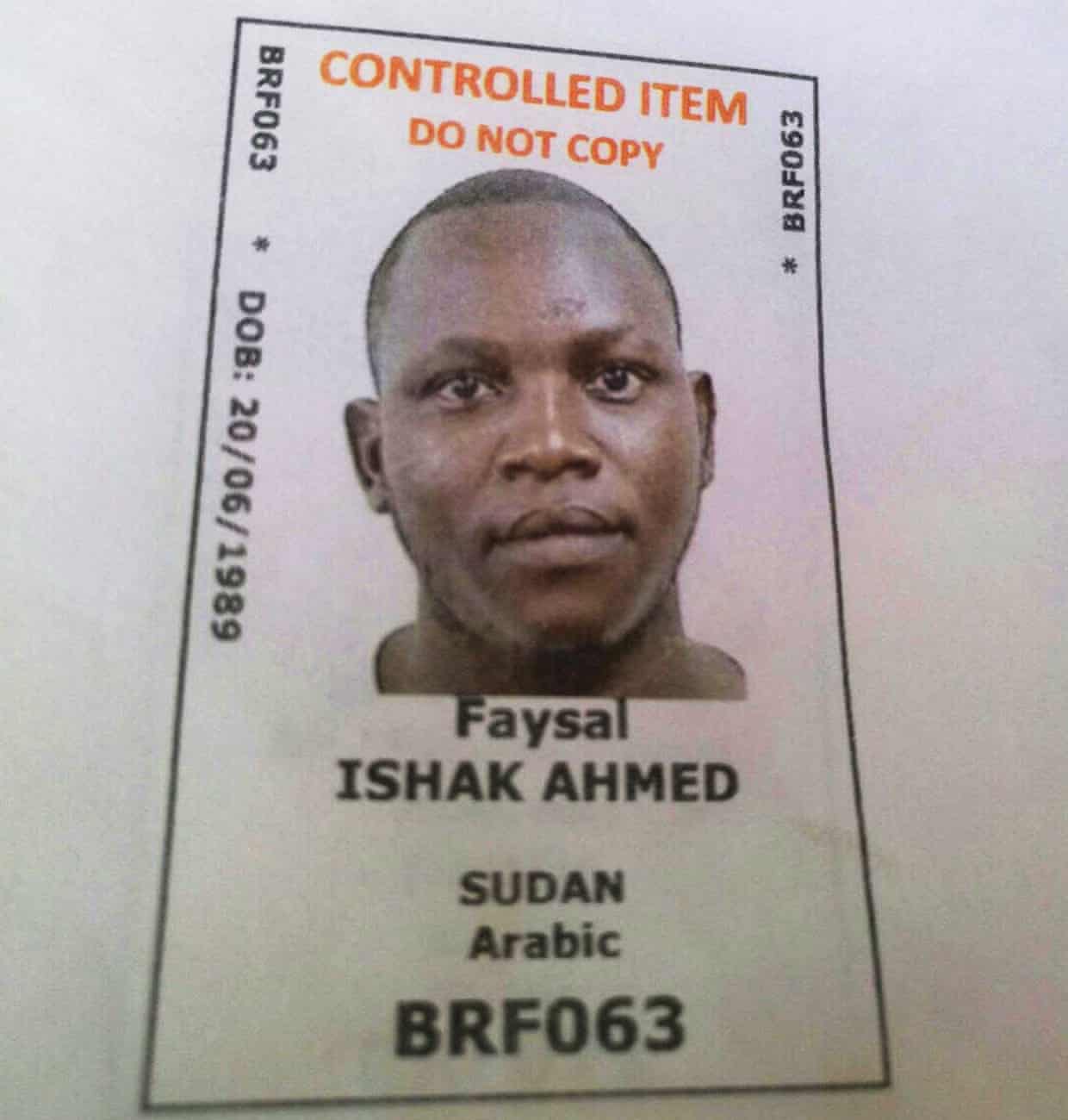

Faysal Ishak Ahmed died on Saturday or was it yesterday … or was it six months ago. Faysal Ishak Ahmed, 27-year-old Sudanese asylum seeker, collapsed inside the detention center on Manus Island, the dumping grounds for those refugees and asylum seekers who seek haven in Australia. This is the same Manus Island where 24-year-old Iranian asylum seeker Reza Barati was killed two years ago. Eight months ago, the Supreme Court of Papua New Guinea declared the detention center illegal. Papua New Guinea and Australia have “agreed” to close the center, but, to no one’s surprise, no time frame has been set. Faysal Ishak Ahmed did not collapse nor did he suffer a seizure. He was killed, and his blood joins the blood of Reza Barati; their blood flows everywhere.

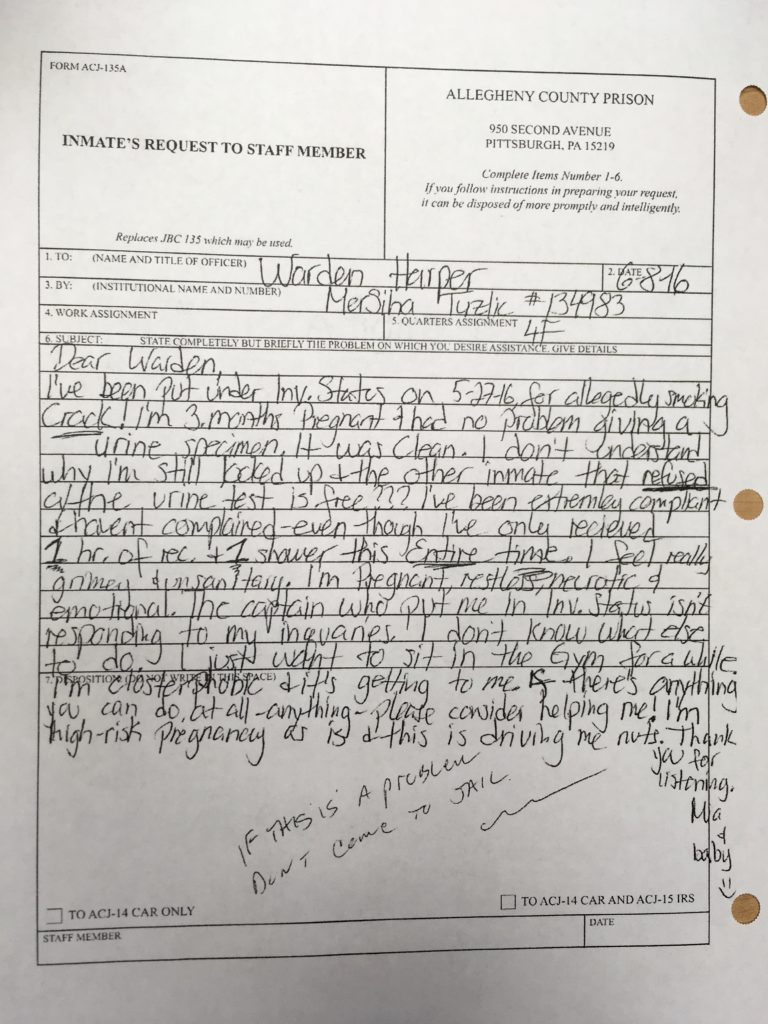

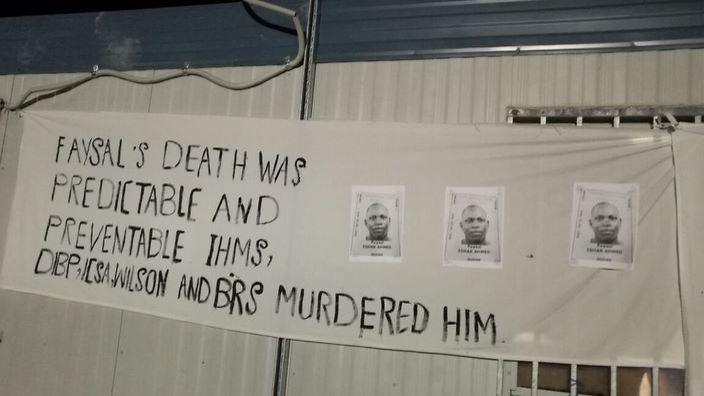

Faysal Ishak Ahmed’s story is all too familiar. For at least six months Faysal Ishak Ahmed complained of chest pains, swollen arms and fingers, high blood pressure and a pain at the back of his head, seizures, blackouts and breathing difficulties. He begged and pleaded for medical care. Fellow prisoners begged and pleaded on his behalf. He wrote letters; fellow prisoners wrote letters. He deteriorated; he received no medical care. When he finally died, the Department of Immigration and Border Protection stated a refugee “has sadly died today from injuries suffered after a fall and seizure at the Manus Regional Processing Centre”. There is no sadness like sadness. Jesus wept, the State shrugged.

The story continues. Manus Island prisoners rebel for a while. Letters are written, protests are lodged, pictures and drawings emerge. In Sudan, Faysal Ishak Ahmed’s parents say they want their body returned to them. They also say that they have not been formally informed of his death by anyone from the Australian or the Papua New Guinean governments. The State’s great and deep sadness continues to oppress the vulnerable and the hurting.

Faysal Ishak Ahmed is just another name, just another death, in the litany of neoliberal global ethics in which he must bear full responsibility for the site of his birth, the color of his skin, and the nature of his faith. It’s Faysal Ishak Ahmed’s fault that he spent three years in prison on Manus Island. It’s Faysal Ishak Ahmed’s fault that he ever asked anyone for help, safety, or haven. It’s Faysal Ishak Ahmed’s fault that he begged for six excruciating, agonizing months without any attention. It’s Faysal Ishak Ahmed’s fault that the medical staff consistently claimed he was malingering and returned to his bed. It’s his fault, it’s altogether Faysal Ishak Ahmed’s fault that his blood flows over all of us. We are innocent, we never saw him, we never knew. It’s Faysal Ishak Ahmed’s fault.

(Photo Credit 1: SBS Australia) (Photo Credit 2: The Guardian)