Take a nap, do a face mask, order a lot of food on UberEats – all elements of the self-care prescription you can find anywhere on the Internet. The meaning of self-care is evident in its name, but the repercussions of its incorrect use are deeper seated than many of us realize.

Twitter (and other social media platforms) have normalized discussions of mental health and self-care. Twitter is a breeding ground for information and online community, which I have felt and been moved by many times. I am inspired by the way online communities can make a home for those who may have none. The baby-boomer era despises technology and social media as a destructive force – it kills our everyday social interaction, makes us “obsessed” with our phones. Social media’s impact on the younger generations of those who use it is quite the contrary – it has taught us how to build community, how to organize, and how to support one another. It creates a shared feeling of connection between distant strangers and can even save lives. Twitter is a fun way to pass the time when procrastinating, but its ramifications on concepts of community are powerful.

The community Twitter has created is not exempt from the deeply embedded neoliberal individualism that the world suffers from today. Even within online communities, “self-care” has transformed into many things and almost none of them are what it should be. You’re a narcissist, you’re problematic, or you’re asking others to perform too much “emotional labor” for you. Self-care is purported to look easy when in reality it should be hard, as it requires the inner dismantling of the oppressive structure of individualism that permeates all aspects of life. Self-care should create community, not isolate those who may be struggling. Self-care can be interpreted in so many different ways that we have lost touch with what it should really look like, and thereby have negatively impacted the community we have worked so hard to create.

What does it mean to perform emotional labor? Twitter may tell you that a friend asking to talk about their hardships requires monetary compensation. Or, Twitter may tell you that setting appropriate boundaries between yourself and others is okay, even encouraged, within the self-care movement. The (mis)use of self-care has led us to unknowingly devalue our own community that Twitter has created. It is exactly through the Internet community that neoliberalism has penetrated, harming the way we view ourselves and others. Self-care and community are intertwined, but the transformation of both their meanings results in a cognitive dissonance that many, including myself, struggle to reconcile.

Self-care is not enough. Even in its purest form, it is accompanied by radical, shared care and trust in one another. We are only as strong together as we are apart. True self care is not selfish, nor is it simple, nor is it individualized. It is a radical feminist practice, allowing us to strengthen ourselves and thereby the movement. As Audre Lorde so eloquently stated, “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.”

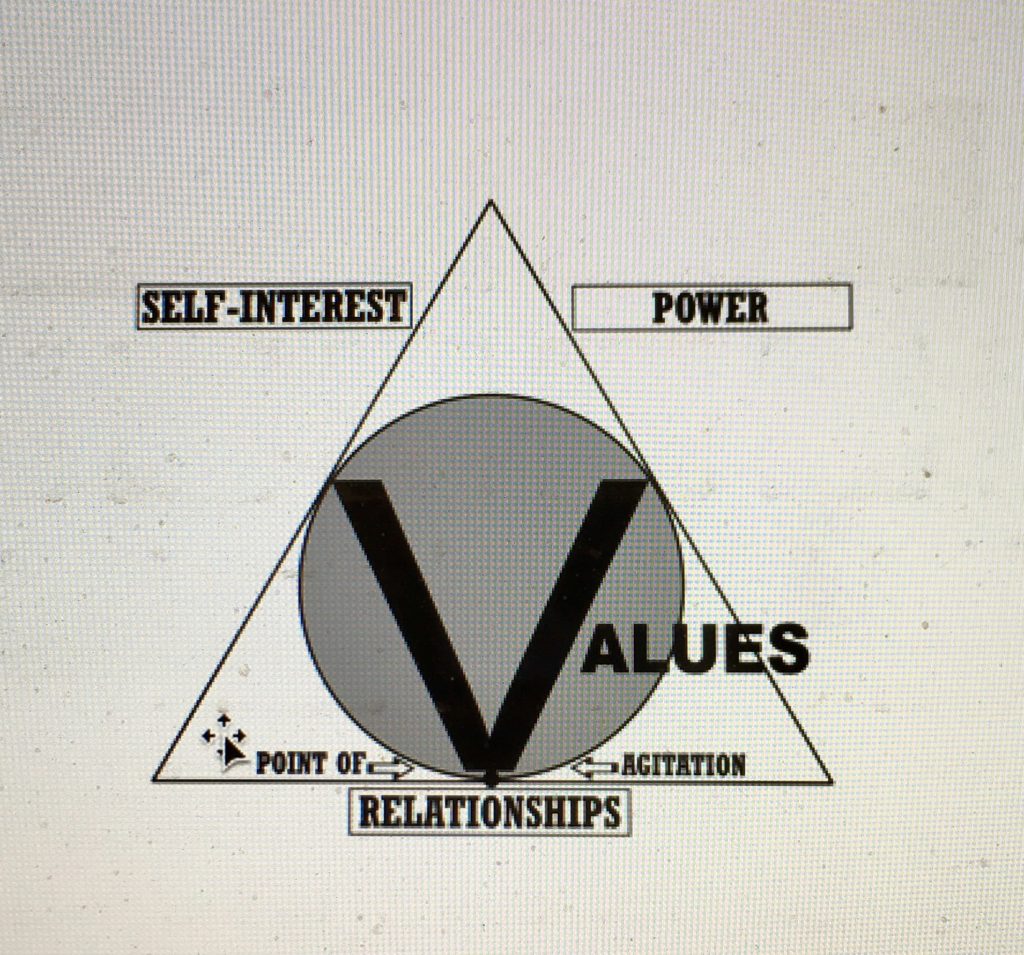

(Image Credit: The Mindfulness Journal)