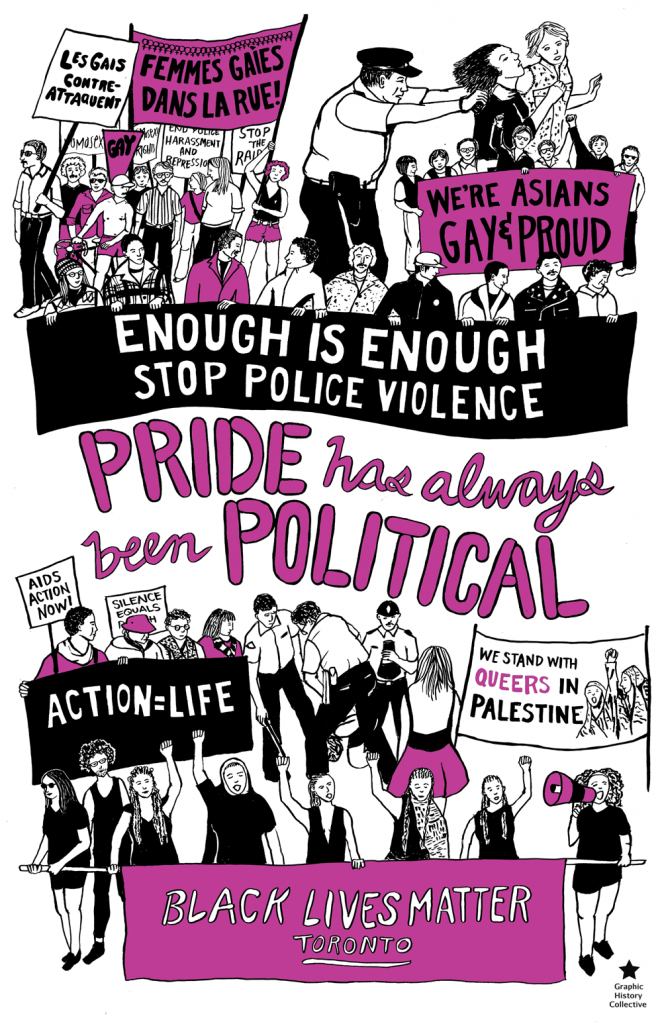

The struggle for queer liberation is bound up in the struggle for decolonization.

The notion, as tweeted by Trump, that queer and trans folx living in the United States should be grateful that they “don’t live in a country that punishes, imprisons, or even executes” them is not only false, it perpetuates a colonial narrative that positions the US and other nations governed by white, western power structures as the civilized and all others as requiring civilizing.

For centuries colonial powers actively exported and imposed queer and transphobic statutes around the globe, and today continue to export missionaries, diplomats, corporations, and more that espouse these same views and maintain a colonial relationship.

Pinkwashing, using LGBTQ ‘window dressing’ to distract from oppressive policies or actions (to LGBTQ folx or otherwise), becomes a useful tool in promoting settler colonialism in Palestine and elsewhere; bolstering racist and Islamophobic narratives and actions; justifying military intervention in countries deemed by the US to be “backwards,” and more. Where queer and trans identities become a tool to maintain power and control over others, there can be no liberation.

(Image Credit: Active History / Kara Sievewright / Gary Kinsman)