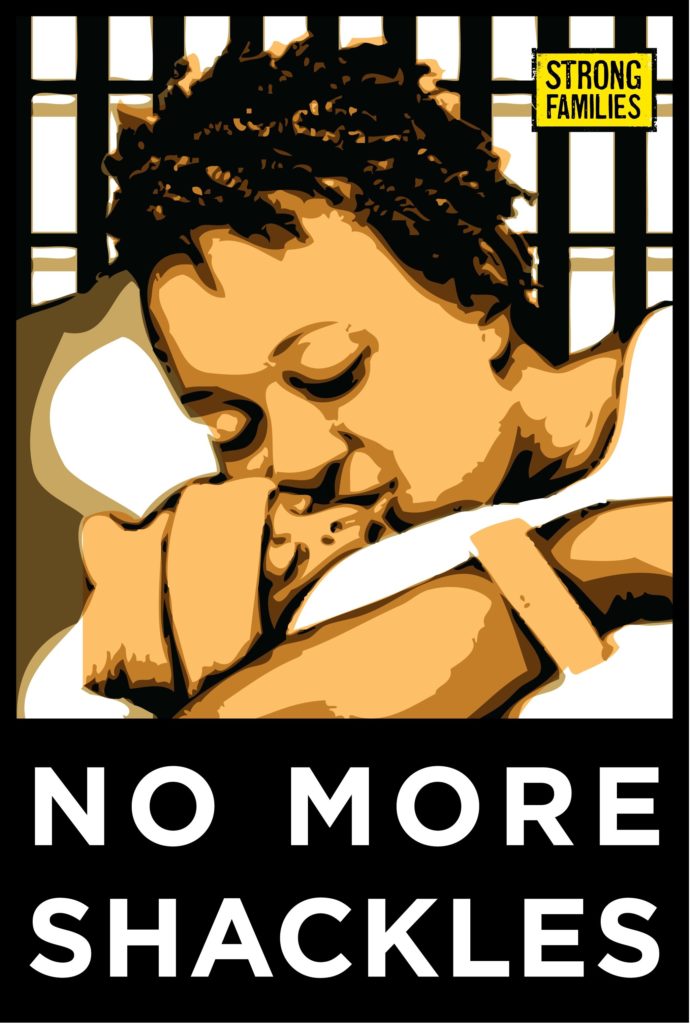

What’s it called when a force seizes women of color and holds them hostage until they, or someone else, pays for their release? Kidnapping? Trafficking? Slavery? In Western Australia, as elsewhere, it’s called criminal justice, and it targets Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. Debbie Kilroy, Executive Director of Sisters Inside, decided that enough was already way too much, and so this past Saturday she organized a GoFundMe campaign to bail out one hundred single Aboriginal mothers. While the effort is terrific, why are women, and particularly Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women still being held hostage by the State?

Here’s Debbie Kilroy’s plea: “Western Australia’s response to poverty and homelessness is imprisonment. Western Australia refuses to change the laws where people who have no criminal convictions are imprisoned if they do not have the capacity to pay a fine. People are languishing in prison for not being able to pay their fines. Single Aboriginal mothers make up the majority of those in prison who do not have the capacity to pay fines. They are living in absolute poverty and cannot afford food and shelter for their children let alone pay a fine. They will never have the financial capacity to pay a fine. So we want to raise $99,000.00 to have at least 100 single Aboriginal mothers freed from prison and have warrants vacated. If you can financially assist this movement it would be greatly appreciated. The funds will only be used to release people from prison.”

In August 2014, a 22-year-old Aboriginal woman, called Ms. Dhu, died in custody in Western Australia. She was being held for unpaid parking fines. Ms. Dhu complained, some say screamed and begged, of intense pains. She was sent to hospital twice and returned, untreated, to the jail. On her third trip to the hospital, she died, in the emergency room, within 20 minutes. It is reported that she never saw a doctor. Her grandmother says she “had broken ribs, bleeding on the lungs and was in excruciating pain.”Ms. Dhu was murdered by State systems of accounting. She was in jail for $3,622 in unpaid fines. The jail staff and the hospital staff decided she wasn’t worth believing or treating. She wasn’t worth the bother, and so Ms. Dhu died and remains dead. No amount of accounting will bring her justice. Her family and community are left to struggle with the State systems of accounting that value their lives as beneath assessment. What does justice for Ms. Dhu mean today?

Ms. Dhu’s case has become the standard by which we mark the incarceration of Indigenous women in Australia, but that doesn’t mean things have improved. A year ago, Human Rights Watch reported“Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in prison are the fastest growing prison population, and 21 times more likely to be incarcerated than non-indigenous peers.” While the report was perfectly accurate, it was also perfectly redundant, given that it reiterated issues came up in major reports published in 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2017. Last month, reporters Hayley Gleeson and Julia Baird wondered, “Why are our prisons full of domestic violence victims?”

Women, particularly Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, end up in prison for unpaid fines. Women suffering domestic violence call the police, and, if they have unpaid fines, the police come … and take the women to prison, as happened to a 35-year-old Noongar woman in September 2017. In what world does that make sense? In our world.

In Australia, rates of incarceration are increasing regularly, and women’s rates of incarceration far outnumber the rates for men. Why? Explanations include criminalization of women’s homelessness, women’s mental illness, women’s addictions, women’s poverty, women’s health. The bottom line is women. Cash bail systems and prison for unpaid fine systems are just another weapon in the State war on women. While Western Australia is the only state in Australia that imprisons people for unpaid fines, the issue is mass and hyper incarceration. As Debbie Kilroy noted, “The wheels are just turning so slowly. This is a priority for many Australians across the country, it’s not just a West Australian issue. It’s nice to say we will get draft legislation in six months but come on.”

We don’t need another report. We need action, and not only in Australia. If you can, consider donating to Debbie Kilroy’s FreeThePeople campaign, here. Whether you do or not, remember the women, around the world, who call the people because they are being abused and end up in prison. It’s way past time to shut that system down. Come on.

(Infographic Credit: ABC)