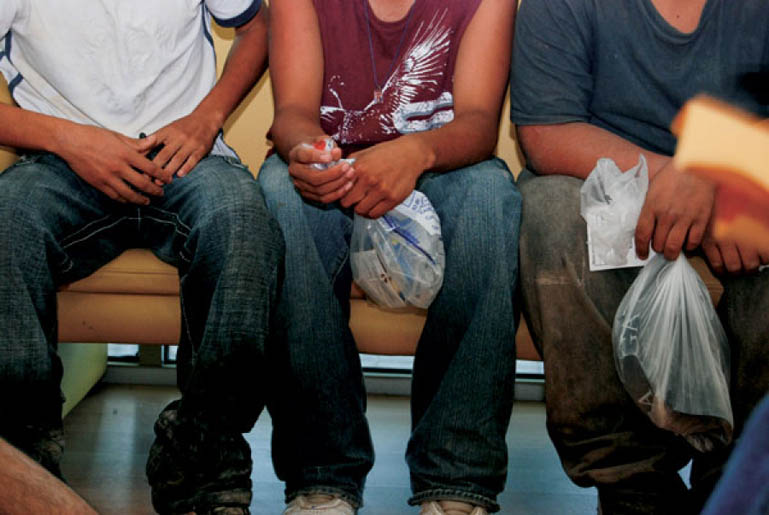

Children waiting in the Desarrollo Integral de la Familia in Reynosa, Mexico

Migration analysts talk about sending and receiving nations. Sending nations are those countries that send, or `export’, its citizens to other countries. Receiving nations are those nations that receive, or `import’ or `absorb’, them. The status of some nation States has changed in the last two or three decades. For example, Italy and Greece were once considered sending nations, and today they are thought of as receiving nations.

Certain countries, such as the United States, are thought of as receiving nations. But that is only the case if the transnational and global export-import business is thought to be one of labor brokerage of national citizens. What are we to call those countries that export non-citizens, those countries that have made a business, a big business at that, of exporting asylum seekers, migrants, children?

Every year, the United States exports tens of thousands of unaccompanied migrant children to Mexico. These children are sent to centers run by Mexico’s social services agency called the Desarrollo Integral de la Familia, or DIF. In 2008, a Mexican congressional committee reported that the United States had deported 90,000 children, of whom at least 13,500 were never claimed. “Never claimed”: that means the children were never reunited with their families.

Who are these children? They are Mexican children who are heading to the north, most often to be reunited with … their families, with their mothers and fathers: “With few exceptions they’ll cross again because their parents or loved ones are en el otro lado and on the other side of the Rio Grande there is hope. Hope to study, to work, or to just hug their mothers or fathers again.”

Susana is in many ways exceptional and in other ways typical of the 90,000 children. First, she’s a girl; 80% of the children are boys. Second, as she sits in a DIF shelter in Matamoros, she says she’s ready to give up, to go home: ““I don’t want to stay here. I’m tired of fighting.” Gender and the intent to return home make her exceptional.

On the other hand, Susana has tried to enter the United States five times, and on each of the five attempts has failed. Every time, she was returned, unaccompanied, to Mexico. Every time, she turned around and tried again. Her father works in Kansas. They haven’t seen each other in five years. He works, struggles, and pays to have his daughter brought over. Each time, the journey costs $2500. Again and again, he pays, again and again she tries. Just to hug her father again. This makes her typical.

The children are sent to centers in Reynosa and Matamoros, centers of the current drug cartel and War on Drugs violence. Reynosa is reported to be one of the most dangerous places in Mexico. Often the children are released to strangers or to distant relatives. Often, some say more often than not, they are returned to the mean streets, and in particular those of Reynosa. So, they then go North because they want to, to be reunited or to study or work, or they go North because they are forced to. Some girls, some boys, may be tired of fighting, but that doesn’t mean they are safe. That doesn’t mean the fighting has tired of them.

What do you call a nation that seizes children, sends them unaccompanied into a violence torn war zone, and then washes its hands of the whole affair, and closes its eyes and ears to the fate of the children? That is neither a sending nor a receiving nation. That is a state of abandonment.

Susana wants to go home, but it’s not that simple. The center wants one of her parents to come and get her. Her father is in Kansas, her mother has to take care of her younger brothers and sisters. And so Susana waits, and like the other 90,000 Mexican children the United States has abandoned to violence and despair, haunts more than the borderlands. Susana haunts citizenship.

(Photo Credit: Texas Observer / Eugenio del Bosque)