It’s been a year, almost, since the massacre at Marikana, and the nation, and its media, are struggling, sort of, to find a way to address all that has, and even more has not, happened in the intervening year. A year later, tensions simmer, the Farlam Commission is more or less falling apart, some great and moving documentaries are beginning to emerge, and the widows of Marikana organize and wait, wait and organize.

This is how the week began. On Sunday, in a prayer service in Langa, national police commissioner Riah Phiyega announced that South Africa would `commemorate’ the Marikana tragedy. How exactly will the police, who used live ammunition to put down a mineworkers’ strike, `commemorate’ the event?

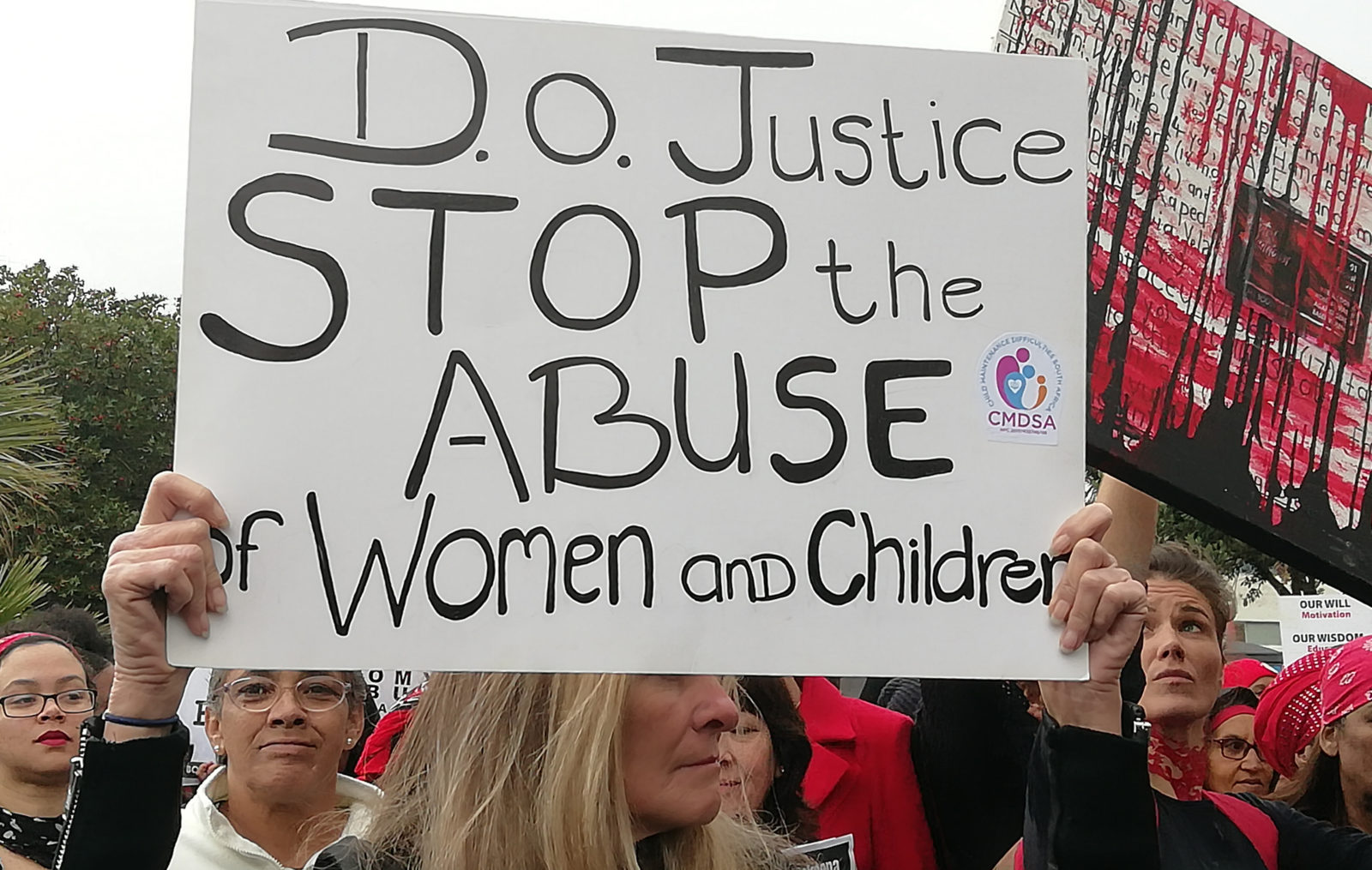

More to the point, is commemoration the best way to honor the dead miners and, even more, their survivors, the widows and children? As one widow explained, soon after the massacre, “Today I am called a widow and my children are called fatherless because of the police. I blame the mine, the police and the government because they are the ones who control the country.”

How will `the nation’ commemorate those who are now called widows and those who are now called fatherless? What happened on August 16, 2012? 34 miners were killed. Many others were wounded. And widows were made. Soon after one mineworker was arrested, police told him, “Right here we have made many widows … we have killed all these men.”

The State machinery, call it a factory, produced widows of women that day, and has continued to produce widows of those very women every single day since. So, here’s a suggestion. Rather than `commemorate’, compensate.

(Photo Credit: Greg Marinovich /Daily Maverick)