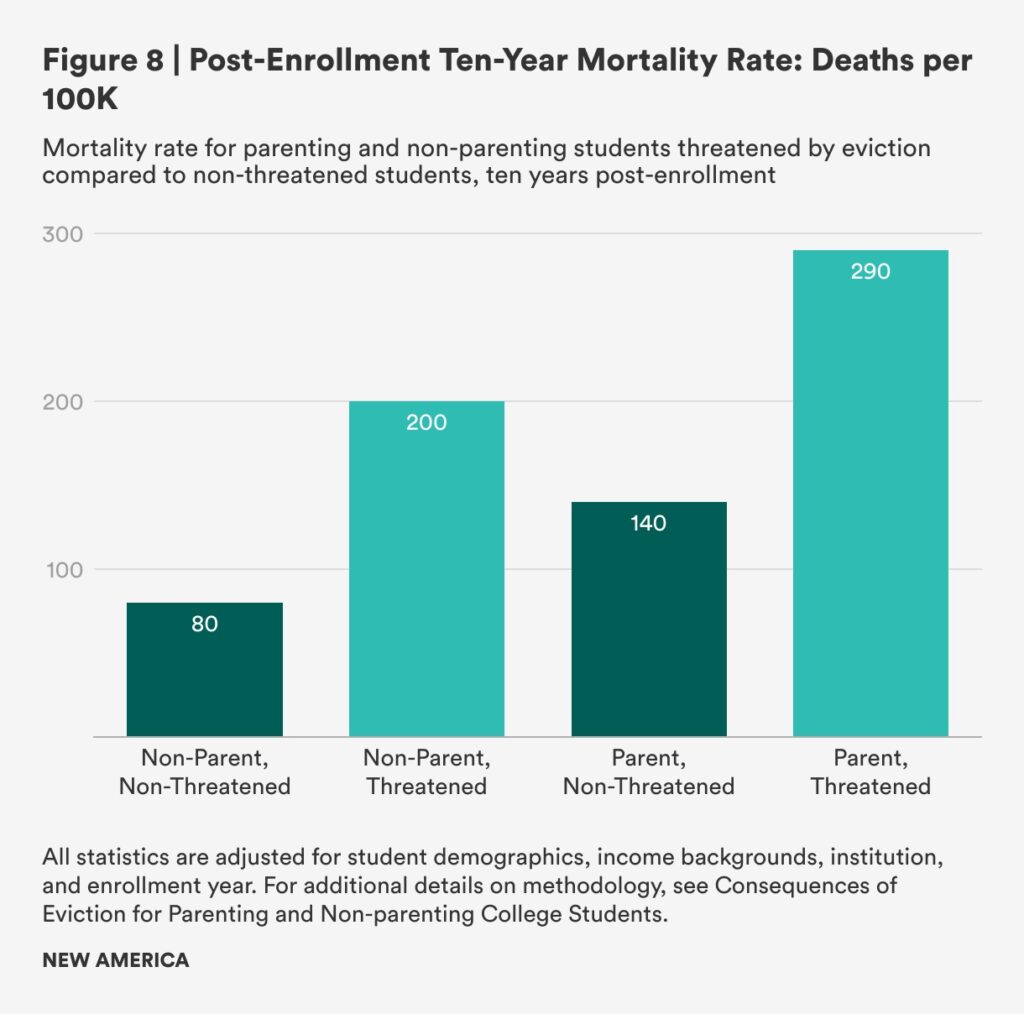

New America, in collaboration with Princeton’s Eviction Lab, released a brief this week, “Ousted from Opportunity: Eviction’s Adverse Impact on Parenting College Students”. While the report is dire and grim and much of the findings are tragically predictable, it’s still worth consideration, especially this, the last of the major seven findings: “Parenting Students Threatened with Eviction Die at Higher Rates 10 Years Post-Enrollment: Parenting students who were threatened with eviction were more than twice as likely to die over the 10 years immediately following enrollment than parenting students who were not threatened (see Figure 8). Threatened parenting students’ mortality rates were even significantly higher than those of nonparenting students who were threatened with eviction.” What else is there to say? What more do you need to know? People who are parents and attending college have a difficult time, often and even typically. People who are parents and attending college who receive an eviction notice die relatively soon after. What more do you need to know?

The data concerning mortality rates come from a report published this month, “Consequences of Eviction for Parenting and Non-parenting College Students”. The authors found the following: “The mortality rate 10-years post-grad is 290 (200-380) per 100,000 for threatened parenting students compared to 140 (110-160) for non-threatened parenting students; in other words, an eviction filing is associated with a 107% increase in risk of death over the next ten years.” Where will you be in ten years? Where were you ten years ago?

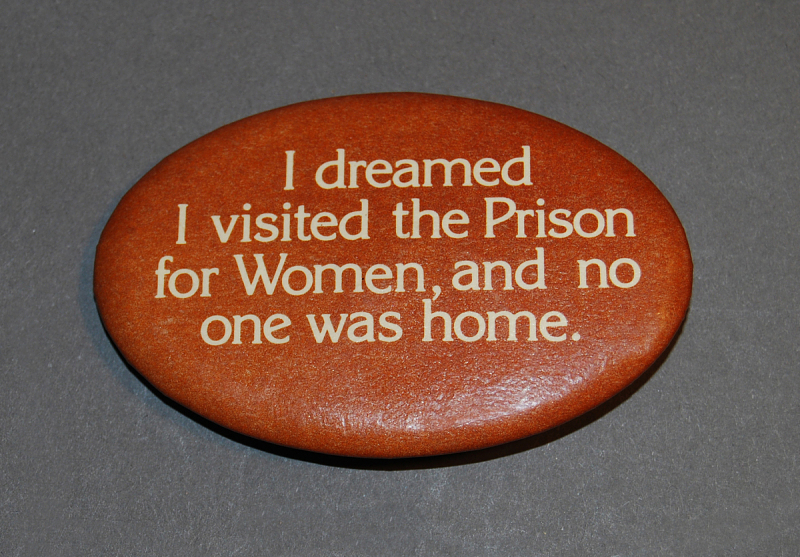

To be clear, this slow-moving massacre does not concern parenting college students who have actually been evicted. This 107% increase in risk of death over the next ten years involves those who have had eviction filings. Who are they? You already know the answers. Parenting students disproportionately come from historically underserved groups. They are more likely to be women, especially women of color, and tend to be older. They are also more frequently first-generation college goers, low-income, and veterans. Student fathers are more likely to be Black than any other racial group. Parenting students have higher rates of food insecurity and are more likely to be working full time. 20% of undergraduate students care for one or more children while enrolled in college. What else is there to say?

The report had seven major findings. Parenting students threatened with eviction tended to be younger than parenting students not threatened by eviction. Parenting students threatened with eviction tend to come from lower-income backgrounds, compared to parents and non-parents who were not threatened with eviction. Black students, whether parenting or not, were far more likely to be threatened with eviction, but Black parenting students are the most at risk. Parenting students who were threatened are much more likely to identify as female, at 81%, compared to 63% of non-threatened parenting students. These are both extraordinarily high percentages. 37% of parenting students who were never threatened with eviction completed a bachelor’s degree, while only 15% of parenting students who were threatened completed a bachelor’s degree. Parenting students threatened with eviction had significantly reduced family income five years post-enrollment.

Parenting students who were threatened with eviction were more than twice as likely to die over the 10 years immediately following enrollment than parenting students who were not threatened

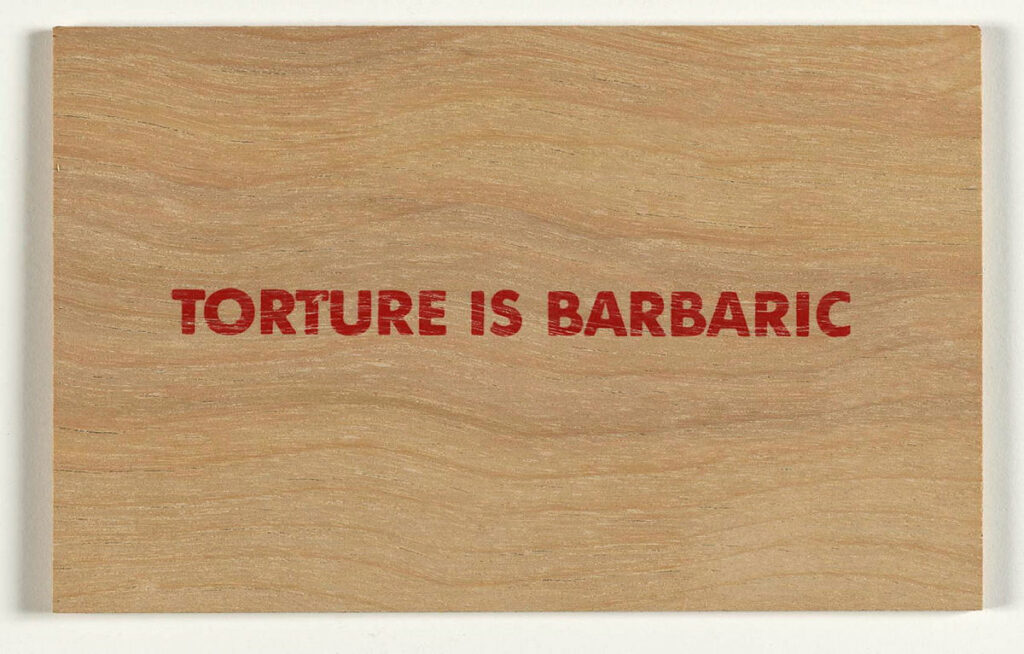

Twenty-two years ago, Achille Mbembe opened his seminal article “Necropolitics”, with these words, “The ultimate expression of sovereignty resides … in the power and the capacity to dictate who may live and who must die.” Who may live and who must die. A young person receives a notice saying they face eviction. No matter what happens, whether they are evicted or not, within ten years they are dead. What else is there to say? What more do you need to know?

Who may live … and who must die?

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Image Credit 1: Day Gleeson and Dennis Thomas, “Title Deed Second Ave.” / hyperallergic)

(Image Credit 2: New America)