Section 27 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa states, “Everyone has the right to have access to health care services, including reproductive health care.” Section 28 of that same Constitution states, “Every child has the right to basic nutrition, shelter, basic health care services and social services.” This week, the High Court of South Africa, Gauteng division, confirmed those sections, in no uncertain terms, in a landmark decision brought by the law and advocacy organization, Section27, and three women: Kamba Azama and Nomagugu Ndlovu, denied free health services while pregnant, and Sinanzeni Sibanda, whose child under six was denied free health services. While the judgement is a decided victory, many question why it had to come to this in the first place.

In 2020, the Gauteng Department of Health issued the Policy Implementation Guidelines on Patient Administration and Revenue Management, which was written and interpreted to allow Gauteng public hospitals to deny free services to pregnant women, lactating women, and children under six. Hospitals began charging exorbitant fees up front before offering any services. They believed provincial policy superseded the national Constitution; effectively, they believed the Constitution was, at best, an interesting document. Section27, Kamba Azama, Nomagugu Ndlovu, and Sinanzeni Sibanda said NO! to that policy and notion, and took the Health Department to court.

Over the last three years, reports of such abuse have increased. For example, “Julian” and his wife and child moved from Maratane Refugee Camp, in Mozambique, to South Africa, seeking, among other things, health care for the infant daughter, who lives with cerebral palsy. As an undocumented resident, “Julian” found only impediments: demands for identity documents, demands to pay upfront as a private patient. Today, he and his family struggle with the R40,000 debt that was imposed on him. Suffer little children …

“Grace Jean”, an asylum seeker from the Democratic Republic of Congo was eight months pregnant and suffered from high blood pressure. After consulting a clinic, she was referred to Charlotte Maxeke Academic Hospital. She went twice to the hospital. Each time, she was told to pay R20 000 to obtain a hospital file number and be treated. Unemployed, Grace and her husband could not come up with the money. She lost the baby.

“Fezal Blue”, an asylum seeker living with HIV, was in labor. She approached three hospitals. None would take her, because she couldn’t provide South African identity card and wasn’t carrying her asylum seeker permit. “Fezal Blue” gave birth in the back of a car, going to a fourth hospital. Mother and child survived, and the baby did receive nevirapine, preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV.

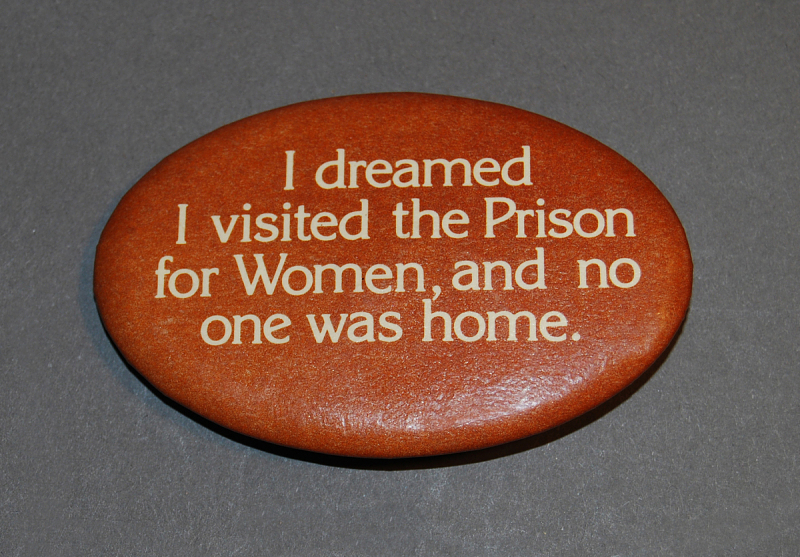

In his decision, Deputy Judge President Roland Sutherland declared Gauteng’s policy to be inoperative and generally an incoherent mess, not to mention a violation of the Constitution. Additionally, he gave all health establishments, across South Africa, until July 17th to post in a clearly visible place, the following: “ALL pregnant women,

ALL women who are lactating, and

ALL children below the age of six

Are entitled to free health services at any public health establishment, irrespective of their nationality and documentation status.”

ALL is capitalized in the Judge’s orders.

The Gauteng policy targeted the most vulnerable: asylum seekers, undocumented persons and persons who are at risk of statelessness. It did more than declare them persona non grata, it declared them nonpersons, unworthy of rights, dignity, or simple human decency. As Mbali Baduza, legal researcher at Section27, explained, “The effect of this court order is that it applies across the country… Medical xenophobia or health xenophobia has been on the rise in certain provinces, and this court order makes it clear that all pregnant women and children under six — regardless of their status — can access hospital care for free… and that’s an important precedent”.

Sharon Ekambaram, head of the Refugee and Migrant Rights Programme at Lawyers for Human Rights and a spokesperson for Kopanang Africa Against Xenophobia, Kaax, noted, “It is concerning that our government needs to be reminded of their constitutional obligations as set out in our Constitution and in our policies. This situation is but one component of a much broader crisis of institutionalised xenophobia”. Dale McKinley, also of Kaax, added, “We should be angry that we’ve had to go this far and that we have to continue to force our government to do the most basic things in terms of what our law says”.

Medical or health xenophobia is nationwide, across South Africa, as it is worldwide, and it’s spreading. Celebrate the victories, such as this landmark decision; and be concerned and angry. Part of the decision was to enforce the rule of law and the power and responsibility of the Constitution, and aprt of the decision was to emphasize the map. No assault on persons’ dignity is unique or individual, they are always part of a pattern of viral growth, and so every response must also be expansive. What happens in Gauteng does not stay in Gauteng.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Photo Credit: Jana Hattingh / Spotlight) (Image Credit: Section27)