Women are organizing a revolution in the highlands of Guerrero, in southwestern Mexico. They are mobilizing and militating in self-defense. They are organizing to protect and extend women’s rights and power at home, in the streets, in the State. They are saying, “¡Ya basta!” Enough is way too much. They are calling women from across Mexico to join with them. These are the rank and file and the comandantes of the Community Police Forces. Nestora Salgado is one of the many women in this growing revolution.

At the age of 20, Nestora Salgado left her home town of Olinalá, Guerrero, and moved to the United States. She left for a better life for herself and her three daughters, and she left to escape a physically abusive husband. Ending up in Renton, Washington, Salgado worked as a domestic worker, at first; sent her daughters to school; divorced her husband; obtained U.S. citizenship; remarried.

At a certain point, Salgado started returning, twice a year, to Olinalá. Initially, she returned to maintain family ties, and to bring material goods to the family, and then to the community. In Olinalá, Nestora Salgado witnessed the ravages of the so-called War on Drugs, which had translated much of the narco-violence to the countryside. She saw the government collude with drug cartels. She saw her community crushed by a political economy of violence, consisting of murder, rape, kidnappings, and wall-to-wall terror and intimidation. She saw violence intensifying, poverty deepening and expanding, and a pervasive sense of abandonment.

Nestora Salgado declared, “¡Ya basta!” She joined a local indigenous community police force. While many in the international press refer to such forces as “vigilante”, in fact their existence is codified in the Mexican Constitution and Guerrero legislation. Initially, Salgado’s security force received major funding from the State of Guerrero. Salgado was elected regional comandante.

Within the first ten months of her tenure, the community police broke the hold of the ruling local gang. Homicide, and most crimes of violence, dropped drastically. Kidnapping practically vanished. And women joined the struggle and moved up through the ranks. Women changed both the war zone of the everyday and the social relations of their own communities.

Then Salgado began investigating and arresting local officials, for their criminal involvement with the cartels. Suddenly, Nestora Salgado went from hero to `terrorist.’ On August 21, 2013, she was arrested and charged with kidnapping. She was carted off to the federal maximum-security prison in Tepic, Nayarit, hundreds of miles away. Despite having been acquitted of those charges, she has been held in Tepic, often in solitary, for almost two years. She has had no trial. She has been denied access to medical treatment.

On May 5, Salgado began a hunger strike. After much dithering and handwringing, and no acknowledgment of the previous two years’ ordeal, the National Commission on Human Rights weighed in, and the so-called Human Rights division of the Ministry of the Interior announced, yesterday, that Salgado would be moved out of Tepic and to a prison closer to her lawyers, family, and comrades.

Nestora Salgado is one of many. Every day, Olinalá and the mass grave of Ayotzinapa grow closer. The number of political prisoners rises as violence against journalists intensifies.

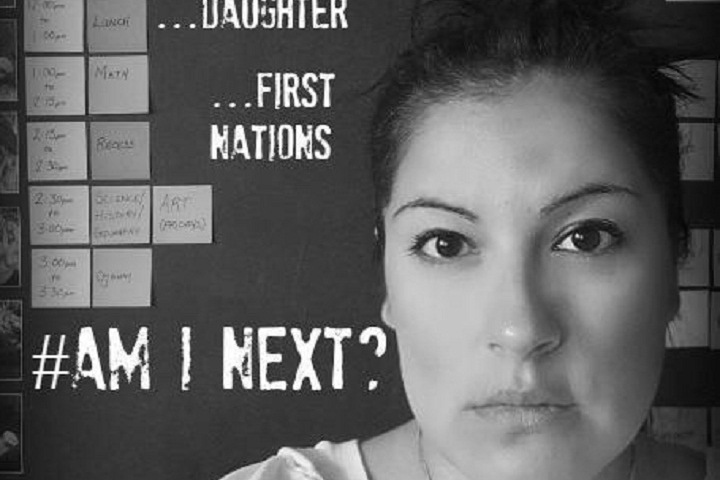

As the violence intensifies, so do the demands for freedom and justice. Nestora Salgado has put it succinctly, “They will not break me and I will not ask forgiveness of anyone.” Indigenous women are organizing and militating. #NestoraLibre appears everywhere. Freedom for Nestora Salgado! Freedom and justice for all indigenous women!

“I’m not afraid of the hired guns or of organized crime. I’m afraid of the State, for the State will disappear me. It’s the State that attacks us.” Nestora Salgado understands that when “organized crime” attacks Olinalá, it’s the State attacking. And when the State attacks … it’s time to fight back. The women of Olinalá demand freedom for Nestora Salgado and for all who stand with her: Release from prison, freedom from State terror and violence … now!

(Photo Credit: La Jornada / Sanjuana Martinez)

(Video Credit:

(Video Credit: