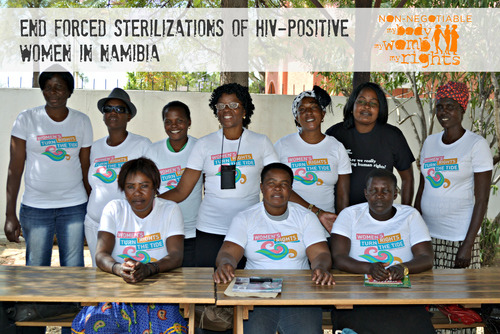

The women of Marikana are marching tomorrow, Saturday, September 22. They have had enough, more than enough, and, as one reporter notes, they are beyond angry. They are incandescent with rage.

They will march as they have marched before, to create a space in which they will be heard, to create a space in which State violence against women, against poor working women, against poor working women’s communities, will end. They will march for peace, they will march for justice, they will march for the incandescent power of their own voices, stories, visions, songs, lives.

Paulina Masuhlo, also known as Pauline Masuthle, will not march with the women. It will be the first time she does not march with them. In the past month, Paulina Masuhlo was often the public face of the women of Marikana. She led the first women’s march after the Marikana massacre.

Masuhlo was an ANC Councillor. She took her job seriously. When the massacre broke out, she met with women in Nkaneng, a cluster of shacks close to Wonderkop. Masuhlo was meeting with women in Nkaneng, when the police swooped down and through the informal settlement. According to eyewitnesses, the police fired rubber bullets, indiscriminately and without provocation. It’s called `a police operation.’ Masuhlo was shot. She died in hospital on Wednesday. The ANC is `shocked’. Others find it `ironic’ that she was shot by the government she represents.

Masuhlo was shot because she was a woman talking with women in Marikana, where everyone is suspect.

This Saturday the women of Marikana will march. Testimony after testimony by Marikana women reveals the fear they live in, they swim and breathe in, as women in Marikana. That same testimony expresses the courage, commitment and organization it takes to tell one’s story … if one is a woman living in Marikana.

Tomorrow the women of Marikana will march, and perhaps incandescent rage will light a path away from death and murder, will light a path to justice.

(Photo Credit: Greg Marinovich/Daily Maverick)