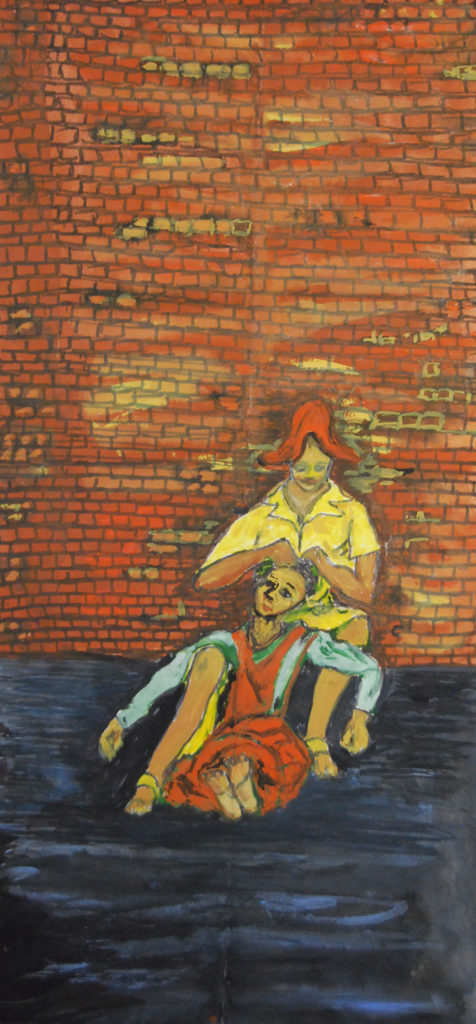

What are you worth (children of Valhalla Park)

Valhalla – the palace of immortality

in Scandinavian mythology –

where rests souls of heroes slain

and there are statues and the like

to the memory of illustrious individuals

What are you worth

children of Valhalla Park

(might some even say

children of a lesser)

I know folks out there

a computer literate mother

of many offspring who

I’ve not seen for a while

(how might they be

are they on the straight

and the narrow path

are they safe there)

What are you worth

children of Valhalla Park

and the immediate surrounds

of your fertile growing minds

Are you worth more

or less than the biologically

blue-eyed and blonde souls

wherever they find themselves

Are you worth more

than your counterparts

in the Palestines Yemens Syrias

of our globalized earth-ghetto

(what of the girl-child

forever at the bottom

of the feeding queue

voting fodder cannon fodder

for politicians and spokesmen)

What are you worth

children of Valhalla Park

What are you worth children

anywhere and everywhere

Penned after a social media condemnation of the recent slaying of children in the area.

(Photo Credit: Voice of the Cape)