“The Federal Correctional Institution (FCI) in Danbury houses low security female offenders and also has an adjacent satellite camp that houses minimum security female offenders…Mission Change: After nearly 20 years of housing a female inmate population, the Federal Correctional Institution is being converted back to a low security male facility.” Welcome to the Danbury Correctional Institution. Welcome to America.

This week it has been discovered that the United States Federal Prison system is dangerously overcrowded. According to Attorney General Eric Holder, “There’s been a tendency in the past to mete out sentences that frankly are excessive.” The Urban Institute released a terrific report, Stemming the Tide: Strategies to Reduce the Growth and Cut the Cost of the Federal Prison System, that argues forcefully for alternative sentencing, more judicial discretion in sentencing, shorter sentencing, and, generally, common and human sense, which is to say uncommon sense. Today, Charles E. Samuels, Jr., Director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons, asked the United States Congress for help: “We are facing significant challenges that are ultimately putting our staff at risk, putting prisoners at risk, and the community at risk.” What exactly is “the community”?

According to Samuels, “Most federal inmates (50 percent) are serving sentences for drug trafficking offenses.” The so-called War on Drugs has ballooned the Federal Prison population from around 25,000 in 1980 to 219,000 in 2012, which puts the United States in first place in the Amazing (Global Incarceration) Race. Despite some increase in federal prison spaces, the current overcrowding results, predictably, in impossible living situations, violence, and generally something between bedlam and mayhem. Plus, the exponentially growing prison population eats up more and more of the Federal budget. It’s a perfect vicious circle.

Missing from the week’s `discoveries’ of the dangers and risks and costs of prison overcrowding are women. So, here’s the story of the Danbury Correctional Institution.

In order to `meet the needs’ of prison overcrowding, the Bureau of Prisons decided to take all of the women in Danbury and ship them off to Alabama. The women are all “minimum and low-security offenders”. No matter. For the Bureau, it made sense to ship these women, and ship is the word, far from their families, communities, and support networks, to make room for the `real prisoners’. Men.

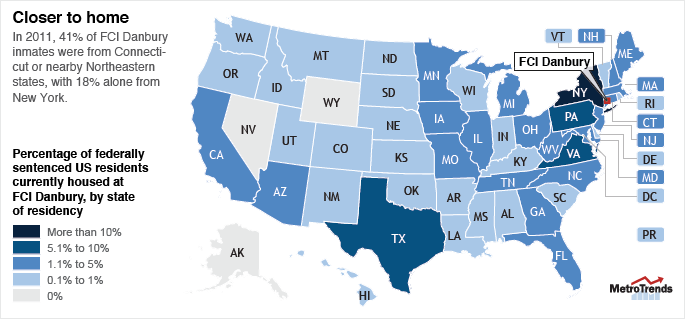

It took two months of heavy lifting by four U.S. Senators – Chris Murphy (D-Conn.), Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.), Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.), and Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.) – and others to finally persuade the Bureau of Prisons to rethink the plan. Apart from the general social justice issue, Gillibrand and Leahy understood that closing Danbury as a women’s facility would have “nearly eliminated federal prison beds for women in the Northeastern United States”. It’s not a local Danbury issue or a Connecticut issue. Closing Danbury would have affected women, women’s families, women’s communities, across the entire northeastern United States. As Senator Murphy noted, “Being sentenced to federal prison is punishment enough. These women shouldn’t be punished again by being removed from their families.”

85 percent of the women in Danbury are not there because of violent or weapons-related `offenses’. 57 percent are drug offenders. They are low to minimum-security prisoners. Why punish them, specifically, doubly and so cruelly in this way? Because, for the State, women prisoners don’t count. The State traffics in women prisoners’ bodies. The value of those women’s bodies is their vulnerability, their collective and individual capacity to be treated like another sack of potatoes. Need more space? Take the women and ship them off. What difference does it or will it make?

(Infographic Credit: Urban Institute)