“Fear not suffering’s gravity.

Return to earth its weighty share;

heavy are its mountains, heavy the sea.”

Rainer Maria Rilke, Sonnets to Orpheus

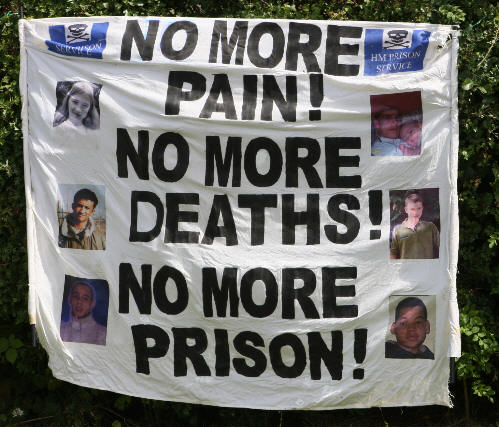

Last week at least 700 people – refugees and asylum seekers – drowned in the Mediterranean. That raises this year’s known death toll to 2000. Italy plans to build a cemetery, a memorial of sorts, to those who die at sea. It would be located next the remains of the country’s largest fascist concentration camp. While the cemetery is the least Italy, or any country, can do, that cemetery is not a “final resting place”. There is no final resting place for those refugees and asylum seekers. This weekend is filled with images of cemeteries and those who come to the cemeteries: families, dignitaries, people. But there is no picture of the surface of the Mediterranean, and there should be. As we stare at the photographs of cemeteries, we should be made to stare at the unbroken surface of the Mediterranean. We should remember all who have perished in the name of war.

One day, impossibly, we will come to the water’s edge and grasp one another’s hands. We will encircle the Mediterranean and we will say the names of every child, woman, and man who drowned in the heavy sea while trying to find haven. Amen.

(Photo Credit: Europe Now)