Children are dying at detention centers on the border. ICE detention centers, which line the pockets of counties like Essex, New Jersey, with millions of dollars each month, have been reported with disgusting health and safety code violations, violating the cushy contracts. Undocumented immigrants in detention at the border have finally won their right to continue protesting with hunger strikes without the fear of nasal tube force feedings. In New Jersey, a Guatemalan toddler died in a state hospital, after being detained by ICE. Her 104-degree fever was ignored before she was reunited with her family in the Garden State. a record number of babies are in detention, raising concerns about the children’s health and wellbeing; and the list goes on and on.

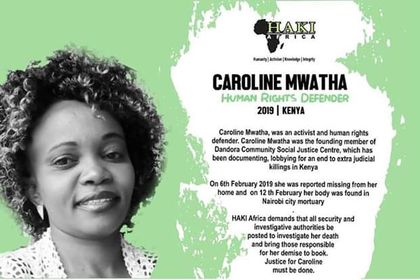

We have reached a crisis moment in the United States when we can ignore the violence and the othering of people, denying them their humanity and justifying carceral violence as a penalty of illegality. Babies and children should not be in detention. Women fleeing violence should not be incarcerated; people should not be put behind bars.

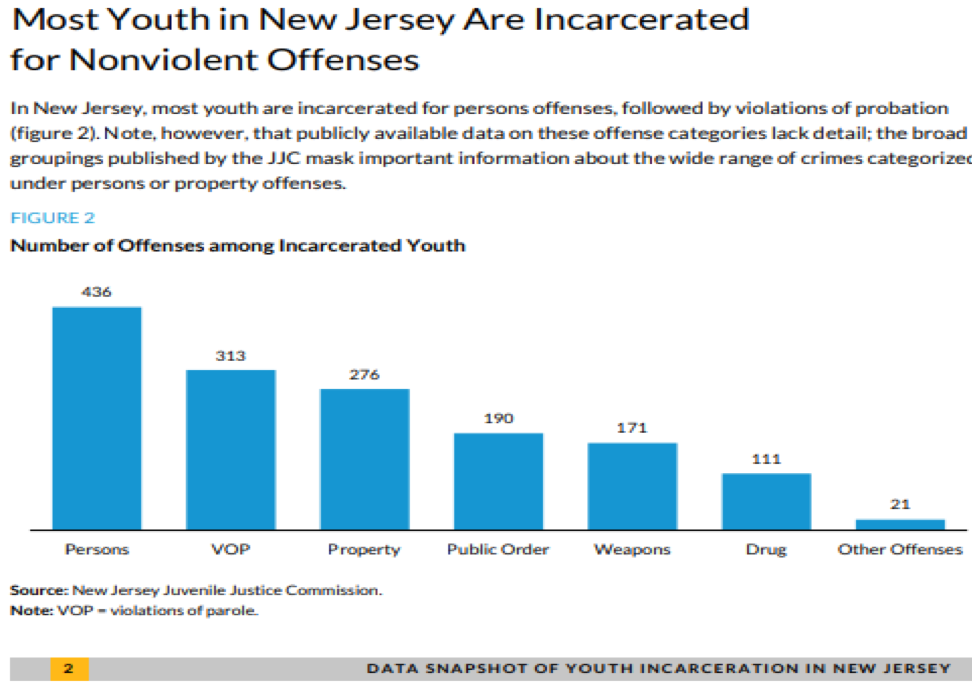

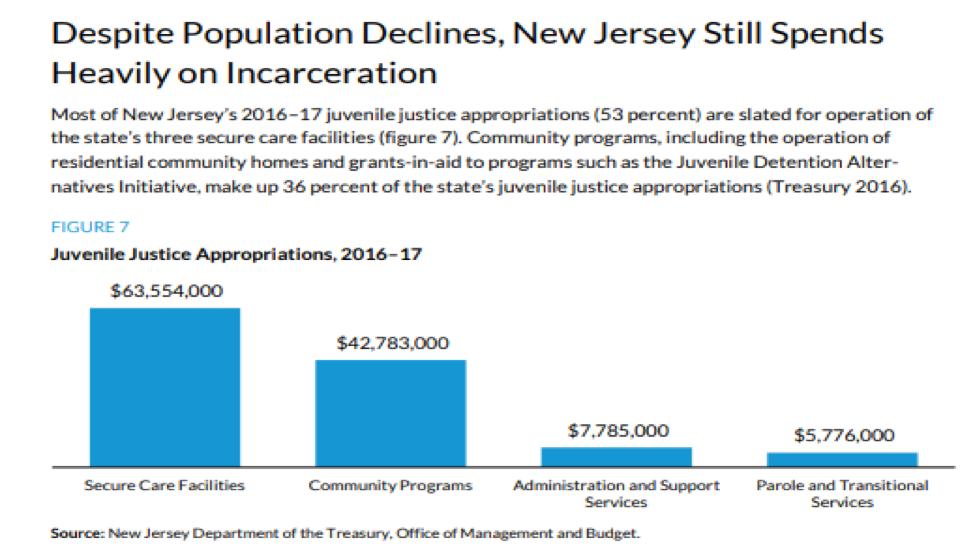

The bubbling incarceration rates of all people in this country, the ties to private prisons that give stockholders millions or billions for putting people behind bars for nonviolent crimes, drug crimes, crimes of self-defense, tickets, misdemeanors, children incarceration: all of this should not be. The crime of being poor and being black or being brown should not be. The lists of should-not-be are endless.

We have more in common with undocumented immigrants in our community, working hard to raise and provide for their families each day, than we do with the billionaires sitting in the oval office and the capitol buildings. We have more in common with the incarcerated than we do with Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates and Betsy Devos. We have more in common with the impoverished and homeless than we do with Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton. The threat of homelessness looms over many in this country, including those who claim to be members of the middle class. I have known the certified letters from mortgage companies, threatening foreclosure and homelessness. Many can relate to earning the bare minimum and working until our bodies have deteriorated. For someone whose entire political career involves an obscene amount of “executive time”, he does not understand the calloused fingers and sore feet of working twelve, fifteen hour shifts and then waking up the next morning to do it again.

We will not become a nation for the people, until we understand that we are all together, all people, all humans, deserving of dignity and humanity, and that we deserve not bars but homes and healthcare, rehabilitation and not violence and felony charges. Prisons give those in power the ability to de-humanize and then justify no one deserving basic human rights: why should the criminal get healthcare when you work for it; why is Narcan for the drug addict free but my medication prices will kill me?

When you realize that the politicians won’t save you, but your common man and women will, then one must organize to demand an end to the inequality and inhumanity in this country and the world. To begin, we must destroy the prison industrial complex.

(Photo Credit: Dialectical Delinquents)