The Legend of Jocko Graves: The [I] Wonder [where we were] Years

In my Summer of Soul I listed to the Keats-ian Grasshopper

Of sweet soul music that would become the soundtrack of my life

That was the same week Woodstock was held

And that Americans landed on the moon

We were singing in Harlem in spite of all

And everything

Contrary to popular belief

James Brown did not teach us that we had Soul

But he definitely confirmed it

And he had a lot of co-signers

Now in my Keatsiian autumn I listen at the crickets

In the resounding silence coming from America’s second political party

As they Whitewash 1/6/2021

That sees the attempted coup as just another day in our country

America

And maybe it was

just business as usual

From the usual American suspects

I juxtapose the Pulitzer Prize winning 1619 Project

To Ahmaud Aubrey’s dead murdered body with sock less feet

And “long dirty toenails”

To an 18 year old White boy made a spokesman for The Right

Embedded with the conservative press

And offered jobs in congressional offices

Shown more deference and respect than an adult Black man

First running for his health

Then running for his LIFE

Not given the benefit of doubt

Had he resisted, three murderers

Would have gone free

People like to tell me that things have changed a lot since my summer of soul

Because we’ve had a Black-ish President

And a Black-ish Vice President

What they mean is

that it has changed for them

I’ve always had Black He-roes and Black she-roes

(and I’m looking at you here PAM GRIER)

They didn’t just show up

It’s just that now

They are widely seen

And others are aware of them, too

I have always been able to “say to myself what a wonderful world”

And I didn’t learn that at a mindfulness meditation retreat

Or from a Jungian analysts either

A nation of millions can’t hold us down

Nor COVID-19

Nor Neo-Nazis

Nor gerrymandering

Nor voter suppression

Will it all be better now just because

The Rolling Stones will no longer sing and play Brown Sugar?

Without asking the question:

Why were they singing in it so loudly and for so long?

How come it tasted so good?

Is Sir Paul MacCartney right?

Were The Rolling Stones just a Blues cover band?

Yeah, yeah, yeah — OOOOOOOOOO!

Cause representation matters.

I’m to old to swing

And so I sing

Sing to younger people with stronger arms and more nimble minds

So that you can swing for me

And swing for yourselves

Representation matters

Growing up we wondered how many times Charlton Heston could save the world:

Free the slaves from Pharaoh

Conqueror the Moors while dead on horseback

Set off the Alpha and Omega bomb on a planet of apes

And be the last man standing in the Omega Man

Until they would pry his gun from his cold dead hands

As he lay in a fountain dying like sci-fi Jesus

Like Rocky, I guess 75,000,000 American voters thought that

That bullshit was real

Ali, boma ye

Ali, boma ye

Ali, boma ye

Ali, boma ye

Ali, boma ye

Ali, boma ye

Shaft came just at the right time,

Just when everybody needed him

Smooth, Leather clad and funky

With his own theme song

Righting all the wrongs

Saving Hollywood and movie theaters

Because no one was believing Charlton Heston’s bullshit any more.

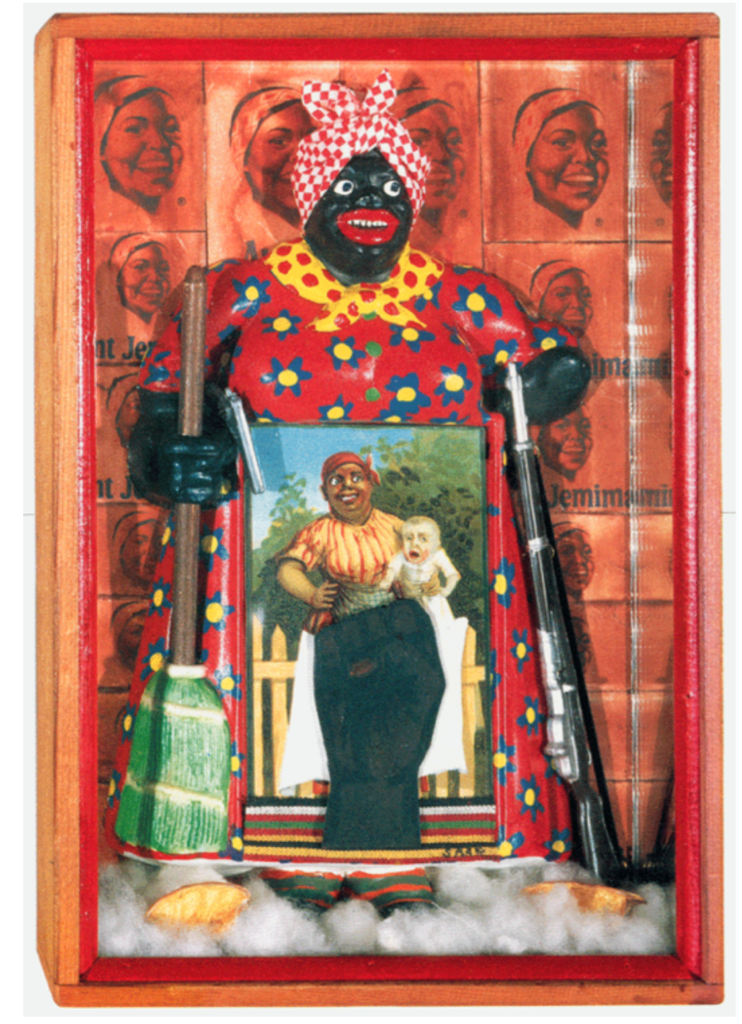

Sing of Urban Myths and the reclamation of Jacko Graves

The inspiration for lawn jockeys

Teenage hero of the revolutionary war who froze to death

Faithfully holding George Washington’s horse

As the pre-first President crossed the Delaware River

To ambush and murder Hessian soldiers in their sleep

It was a myth that became so pervasive, That our neighbors painted their lawn jockeys white in protest

That is

Before the White flight made them move out of the city

And into the cloistered suburbs

To hide behind gated communities

This poem is for

The Legend of Jacko Graves

and

“The [I] Wonder [Where We Were] Years” between my Summer of Soul

And my contemplative autumn

But before my winter of discontentedness

‘Cause everyone wants to go to Heaven

It’s just that nobody likes to die.

(By Heidi Lindemann and Michael Perry)

(Image Credit 1: Betye Saar, The Liberation of Aunt Jemima. The Berkeley Revolution)

(Image Credit 2: Chase Hall, Jocko Graves (The Faithful Groomsman), Jenkins Johnson Gallery)