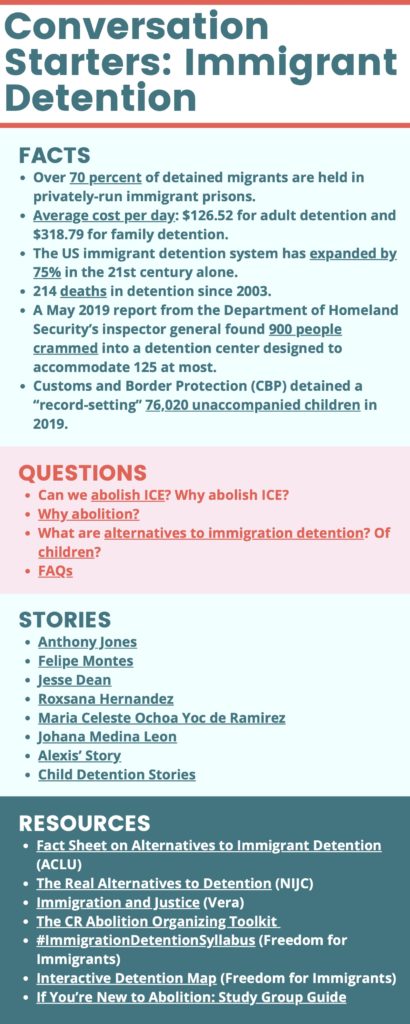

Sri Yatun cooking at home

The story of Sri Yatun illustrates the resilience and courage of domestic workers, while revealing the corrupt global networks of shared reproductive labor that harm low-income female migrants and make their lives increasingly precarious. It also demonstrates how ‘the global’ facilitates the exchange of migrant domestic labor as the underpinning of a globalized capitalist economy; in doing so, it suppresses the voices and experiences of migrant domestic workers. To understand the experiences of domestic workers we must ask: Why are their experiences rendered invisible? How is this invisibility intentional and constructed? Sri’s story is equally devastating, instructive, and revolutionary. The details of her life demonstrate how the ‘global’ leverages migrant domestic workers’ state of precarity to silence them. Experiences like those of Sri are not unintended side-effects of State Department programs; rather they are intentionally crafted, sociopolitical notions of whose lives matter and whose do not.

For migrant domestic workers, like Sri, precariousness is an embodied state of being through their experience of liminal legality: they are aware their residency in the US is fragile and potentially fleeting. As such, they embody a liminal space and a physical precarity that colors their everyday interactions, duties, and behaviors. Notions of belonging, as codified through national identity, enforce precarity in the lives of migrant domestic workers. The fear of deportation places them in an incredibly vulnerable position in employer-employee relationships, promoting their silence in the face of exploitation. For Sri, the interplay between her status of liminal legality, the powerful status of her elite diplomatic employers, and the invisibility she faced in the home, obscured the abuses she faced at the hands of Cicilia and Tigor. She was afraid to speak out, depowered by the very system that relies on her labor to function.

Sri is a survivor of mental and emotional abuse at the hands of her employers. Despite caring for their family–raising their child–Cicilia and Tigor treated Sri as a slave, frequently beating her and verbally berating her. The house in which Sri lived and worked was also the sight of a daily war, one in which she was depowered, vulnerable, and exposed. Sri was an outsider in the home she maintained. She had no way to protect or defend herself, an especially violent social existence, akin to Mbembe’s concept of the death-world. The article notes harrowingly that, “Wearing [Tigos’s] son provided a measure of protection against his outbursts.” Even this limited sense of security, however, dwindled throughout the years as the son became less reliant on Sri’s care. This utilization of the body and mind as the tools of labor, also left significant consequences for Sri’s health. She notes in the article that she “has pain in her back and knees. ‘Little things to remind me,’ she says.” Her body, then, is a tangible reminder of the verbal and physical abuse she faced at the hands of her employers–each ache, sore, and crack, a remnant of her years of exploitation.

Sri was a caretaker for many years, raising children who were not her own. Given that experience, one may assume she would be an expert in all forms of caring. Sri was not prepared, however, to be a caretaker for someone she knew affectionately and intimately. Sri’s experience caring for ‘mama’ in her old age illustrates a divide between caring as a profession and caring for your family. Her multi-faceted experiences of giving and receiving care elaborates upon the grief and loss inherent in every step of her life. As excerpted from the article:

“Sri had taken care of so many people, but it felt different to look after Mama. She’d started her career in caregiving with strangers who had felt entitled to extract what they wanted from her; she’d also cared for kind and generous people, and everyone in between. She’d mastered the domestic worker’s art of invisibility: the ability to take in everything in a home and render her own self unseen to avoid disrupting her employers’ perception of their privacy. So none of her experiences could prepare her for what it was like to care for — and potentially lose — the woman who had found her, who had truly seen her, at a gas station 14 years earlier.”

Grief shapes the lives of domestic workers in many ways: grief for elders who pass, grief of a child who moves on, grief of the family you thought you were a part of. Some workers grieve alternate employment prospects, or a stable wage. Others experience grief as they care for children a world away from their own. Many grieve the life they should have had. As such, grief cannot be disentangled from domestic work. For years, Sri’s desire to grieve–her jobs, dreams, the children she cared for a long the way–was suppressed in favor of economic survival. She had to keep going, working, and fighting for a better life. Finally, after years of this precarious struggle, Sri found someone to take care of her in her grief–the community–a radical act of communalized care in an undervalued community.

(By Alex Groth. Alex Groth believes everyone should be cared for.)

(Photo Credit: Washington Post / Barbara Davidson)