The International Labour Organization released a major study today, Domestic workers across the world: Global and regional statistics and the extent of legal protection. Though the report’s picture is largely what one might expect, it’s still worth engaging.

In 2010, at least 53 million women and men worked as domestic workers, up 19 million from the last count of 33.2 million people, in 1995. That’s almost a 60% increase in the size of the global domestic labor force. And remember, the numbers are always lowballed, so that the ILO suggest there could be as many as 100 million domestic workers.

Globally, universally, everywhere, domestic workers are overwhelmingly women. Which women might change from place to place, but they’re always women. Globally, 83% of domestic workers are women. Globally, 1 in every 13 women wage earners, or 7.5%, is a domestic worker. In Latin America, 26.6% of women workers are domestic workers. In the Middle East, 31.8% of women workers are domestic workers.

In the United States, 95% of domestic workers are women, of whom 54% are women of color. Latinas make up the largest group among the women of color domestic workers.

This means the status and state of domestic workers is part and parcel of the pursuit of gender equality. Addressing the inequities of domestic workers’ lives and situations is key to women’s emancipation … everywhere.

The United States gets something of a free pass in the report, but it shouldn’t. Here’s why. The report focuses on three areas of major concern: working time; minimum wages and in-kind payments; and maternity protection. Paid annual leave falls under the category of working time, and guess what? Of the 117 countries in the report, the United States is one of only three countries without a universal statutory minimum for paid annual leave. The other two are India and Pakistan.

When it comes to coverage of domestic workers’ control over their time, the United States is the only so-called developed country and the only country in the Americas that excludes live-in domestic workers from overtime protections.

The picture is worse when we turn to maternity leave. Among so-called developed countries, only the United States, Japan, and South Korea have no entitlement to maternity leave for domestic workers and no entitlement to maternity cash benefits. In the Americas, the United States is the only country that has neither maternity leave nor maternity cash benefits for domestic workers.

At the beginning of the 20th century, women were described as “being forced to become servants”. A hundred years later, they are described as “preferred by employers.” That’s the march of neoliberal progress. You weren’t forced; you were preferred. Otherwise, it’s been a century of exclusion of domestic workers from protective labor legislation.

It’s time to end that century. Domestic workers are under attack. They’re under attack because they are women. End the exclusion of domestic workers from national labor laws. Domestic workers are women workers are workers. Period.

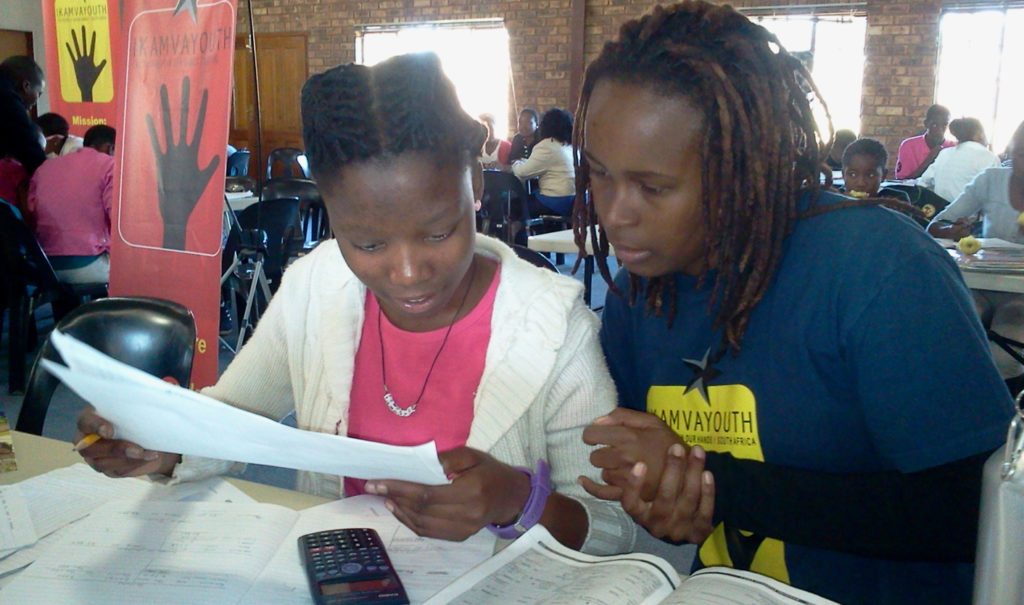

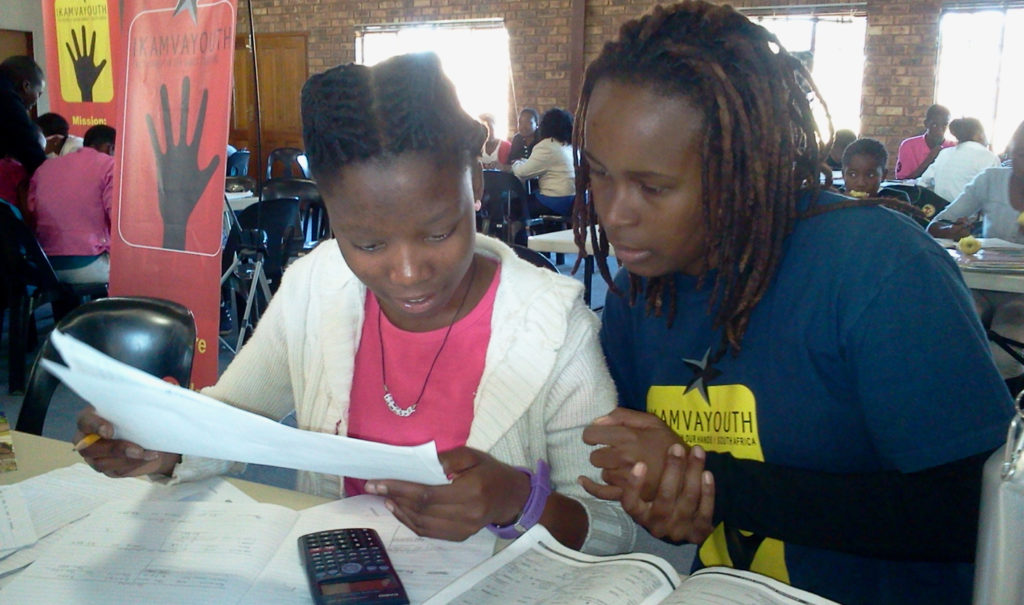

(Photo Credit: ACelebrationofWomen.org)