What is neglect? More specifically, what is State neglect? In the past week, people have been reported to die of neglect at the hands of the State in Egypt, the United States and South Africa. What does that mean? Too often, the story of neglect is recounted as one of oversight, an omission, an act of forgetfulness, but State neglect is public policy, and its consequences can be catastrophic, as this week has shown.

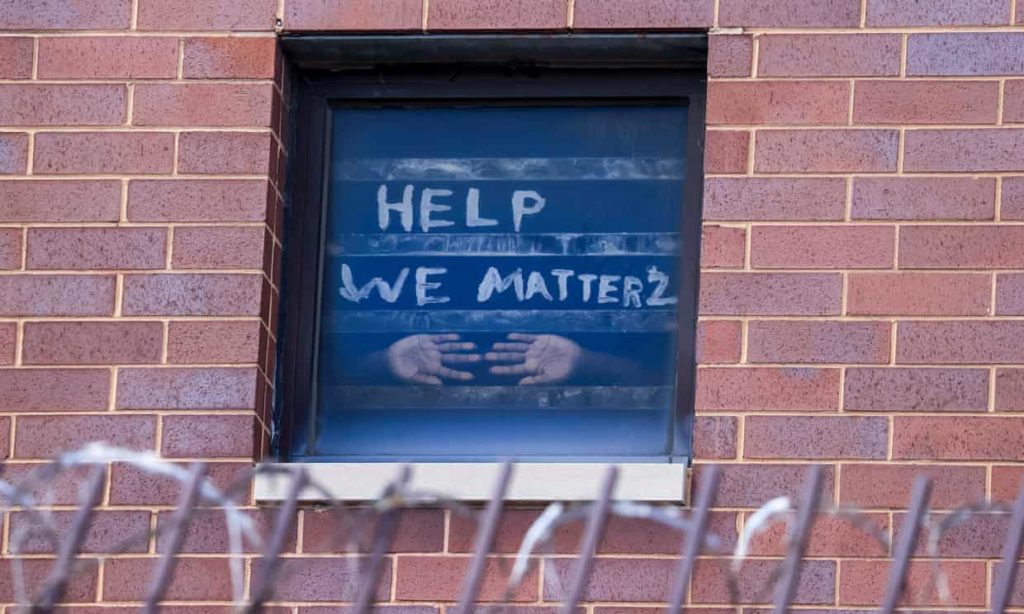

According to the Egyptian Network for Human Rights, ENHR, since the beginning of 2023, twelve people have died of `medical neglect’ while held in prisons and detentions centers. Last week, Madyan Hussein and Sameh Mansour died of neglect. They were not forgotten in a corner somewhere, they, as so many others who have died while incarcerated were effectively executed.

Last year, in Atlanta, Georgia, Lashawn Thompson died in the Fulton County Jail. Lashawn Thompson was 35 years old, Black, living with schizophrenia, homeless. When he died in a bedbug infested bed, his family demanded an independent investigation. This week, the autopsy was concluded: “The death of Mr. Lashawn Thompson resulted from severe neglect evidenced by untreated schizophrenia, poor living conditions, poor grooming, extensive and severe body insect infestation, dehydration, and rapid weight loss”. “Mr. Thompson was neglected to death”. Neglected to death.

Hammanskraal is a rural community under the supervision of the Tshwane Metropolitan Authority, in northern Gauteng, in South Africa. This week, as of last count, 17 people in Hammanskraal died of cholera, and 100 have been taken ill. Hammanskraal is in the news this week for the `neglect’ that led to this disaster.

Yesterday, in the Mail & Guardian, Ozayr Patel wrote, “South Africa was long known for its clean water, but not for at least the past two decades. Now that a cholera outbreak in Hammanskraal has, at the time of writing, claimed the lives of 17 people and left about 100 ill, the water crisis is making headlines …. The M&G has covered numerous stories from around the country about water treatment plants being neglected, not working, and sewage flowing down streets, into people’s yards and into rivers and streams. Now that 17 people have died, will something be done? Or are we more likely to see results if more people die?” Patel’s account partly relies on Anja du Plessis’ research. Earlier in the week, in a piece entitled “Cholera in South Africa: a symptom of two decades of continued sewage pollution and neglect”, du Plessis wrote, “The unacceptable level for operations indicates that the operation of treatment systems and risk to infrastructure is of concern and not efficient. The data emphasises the non-functioning and overall neglect of wastewater treatment works.” In the Daily Maverick, Thamsanqa D Malinga agrees, “Hammanskraal is the straw that will break the camel’s back, the one scandal that has just helped shine the light on the neglect of the poor. Its advantage is that it falls under the control of one of the biggest metros in the country — and our capital city.”

Meanwhile, elsewhere in South Africa, “Apart from the recent spike in cholera deaths caused by dirty water, residents of Mokopane in Limpopo fear also contracting water-borne diseases such as malaria and typhoid. And they accused their municipality, Mogalakwena, of neglecting them.” The neglect was elsewhere described as `reluctance’.

What is neglect? Under Abuse and neglect of children, the Code of the Commonwealth of Virginia declares, “Any parent, guardian, or other person responsible for the care of a child under the age of 18 who by willful act or willful omission or refusal to provide any necessary care for the child’s health causes or permits serious injury to the life or health of such child is guilty of a Class 4 felony.” Elsewhere, in its discussion of Abuse and neglect of vulnerable adults, the same Code defines neglect: “`Neglect’ means the knowing and willful failure by a responsible person to provide treatment, care, goods, or services which results in injury to the health or endangers the safety of a vulnerable adult.”

What happened, and is happening, in Egyptian prisons and detention centers, in the Fulton County Jail, in Hammanskraal is knowing and willful failure by those responsible to provide treatment, care, goods or services, resulting in injury, endangerment, harm, and, finally, death. Yes, Hammanskraal was years in the making, and the residents of Hammanskraal protested the violence being done to them … to no avail. Don’t call it neglect, call it murder, committed by the State, call it a crime against humanity.

(By Dan Moshenberg)