Women, peasants, workers, artists, mothers, and other marginalized people and communities are at the forefront of the struggle in the Philippines. Their identities and struggles intersect and overlap as they fight for gender equity, land reform, labor rights, living wages, and divorce rights, among others. They are all suppressed at the hands of the fascist, authoritarian, machismo state which began long before the administration of Pres. Rodrigo Duterte, but significantly increased during his time as the country’s top leader, and continues under the new Ferdinand Marcos Jr. presidency.

Pres. Duterte’s term was notorious for his war on drugs that resulted in thousands of deaths and extrajudicial killings of the urban poor and marginalized; passing the Anti-Terror Law in order to red tag dissidents; shutting down and threatening media outlets for critiquing him and his administration; and consistent misogynistic comments made during official speeches and press conferences. Under Duterte’s administration, several community advocates and political activists were jailed on false charges or killed by the military. Most notable are the cases of Amanda Echanis, daughter of slain peace consultant and peasant organizer, Randall Echanis, and Reina Mae Nasino, whose newborn daughter died while separated from her imprisoned mother.

Organizations such as Rural Women Advocates and Gantala Press have been instrumental in the advocacy for their releases and for spreading information and awareness of other causes and struggles in the Philippines. Although they are part of larger organizations and coalitions, such as Gabriela and Amihan, who have more political power and international chapters, RUWA and Gantala Press advocate for their messages and causes through social media and the promotion of the arts and literature.

Rural Women Advocates or RUWA are volunteers of the Amihan National Federation of Peasant Women. Amihan is a political party that campaigns for representation in Congress and at other important events and committees in the nation’s capital region. RUWA uses social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter in order to organize and share events such as printmaking, community cooking, general body meetings, fundraisers, online campaigns, infographics, and other publication materials. RUWA volunteers who live in Metro Manila work in solidarity with women peasants in the rural and countryside regions to elevate their voices and bring more awareness to the issues they face. This is important because peasant and worker issues affect everyone, regardless of their location or positionality in class and society.

Meanwhile, Gantala Press identifies itself as a “Filipina Feminist Press” who also advocate for women in the margins of Philippine society, including queer and trans women, and victims of state violence, to name a few. The small alternative press publishes chapbooks, anthologies of poetry, prose, and essays, cookbooks, comics, zines, and other feminist and artistic resources that would have been overlooked or rejected by bigger, traditional printing presses. They allow for their writers and contributors to have a larger audience and an archive for their work to be accessible to others. The press also organizes creative workshops, book and art fairs, and fundraisers to support women and artists in their community.

The use of social media and alternative publishing has allowed for these two grassroot, feminist organization to reach more individuals in the struggle and create a larger network of feminists, activists, and allies. The accessibility of their content and writing, both operating in English and Filipino, has allowed them to connect to both Filipinos living in the country, both rural and urban, but also to Filipinos outside the country, and non-Filipinos who sympathize with them and their causes.

Both organizations show the intersectionality of the struggles of women, peasants, workers, mothers, queer folk, creatives, and activists in the Philippines. Their campaigns often intersect in subject matter and overlap in duration or approach. Both RUWA and Gantala press have proved that there can be rural-urban-local-global solidarities.

These struggles and resistances are reminiscent of Chandra Mohanty’s essay, “Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses.” Filipino women can experience transnational and rural-urban solidarites and connections, but the solutions and means of resistance must come from the women and peasants working at the grassroots level, at the front line of the struggle. The struggle must also be a continuous process, one that can last over a lifetime through small and even “weak” resistances, working alongside the goal of drastic and bigger movements towards revolution.

Solidarity and utopian thinking are imperative to the sustainability to any struggle and long term fight. Even if we cannot be together physically, knowing that you have allies who take on your oppressions and struggles as their own and work alongside you to do social and cultural work is important in motivating us and giving us hope. As Sara Ahmed reminds us in Living a Feminist Life, feminism is in the everyday acts of resistance against the patriarchy, the state, and society. These seemingly small and ordinary acts and crucial to the work we put towards imagining a better and brighter future where all of us are liberated and happy.

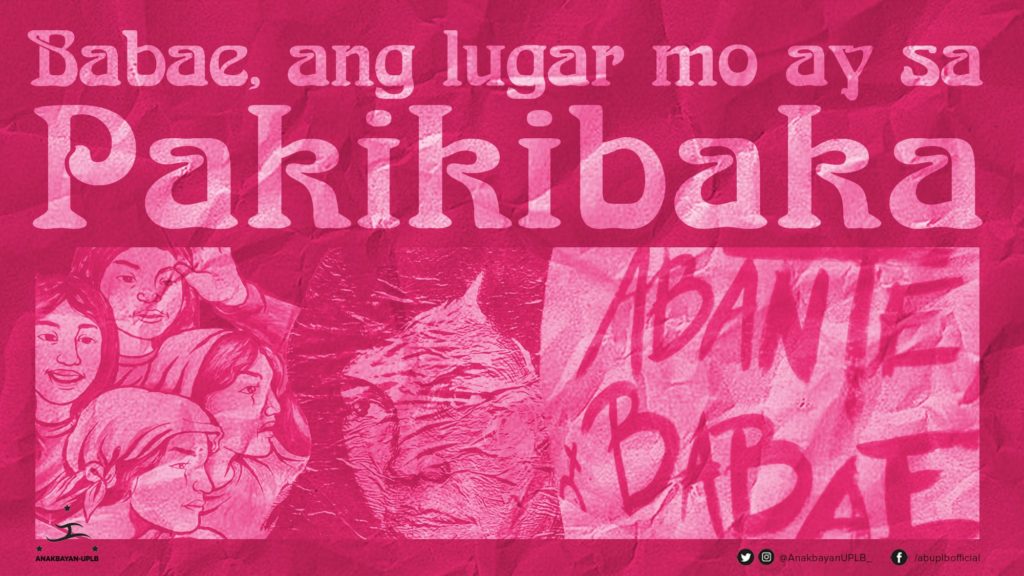

Babae, ang lugar mo ay sa pakikibaka. Whether we are conscious of it or not, join a organization or not, realize our everyday acts of resistance or not: women, our place is in the struggle. Our place will continue to be in the struggle until each and everyone one of us has been freed.

(By Wella Lobaton)