Lumka Mketwa

“Who will honor the city without a name

If so many are dead … “ Czeslaw Milosz, “City Without a Name”

“Childhood? Which childhood?

The one that didn’t last?” Li-Young Lee, “A Hymn to Childhood”

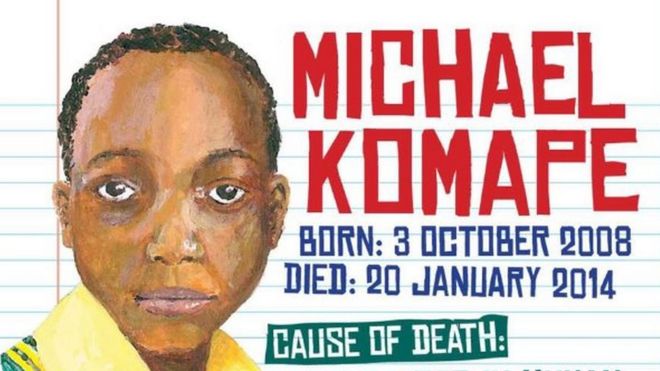

On Monday, March 12, 2018, five-year-old Lumka Mketwa went to the toilet at her school, Luna Primary School, in Bizana‚ in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. She never returned. She wasn’t found until the next day. When authorities “reported” her death, they said her name was Viwe Jali. Lumka Mketwa went to the bathroom and drowned in a pool of human shit. No one even noticed until she didn’t show up for her after school transport. Then her parents and the community searched frantically. They found her the next day. The State never came. The parents did, and when they finally found her, the State refused her the dignity of her own name. They might as well have named her Michael Komape, the five-year-old child who, in 2014, drowned to death in a pit latrine at the Mahlodumela Primary School, in Limpopo, South Africa. In the Eastern Cape, as in Limpopo, the State never came. The State refused to acknowledge and refused to act. As with Michael Komape, Lumka Mketwa did not fall to her death in a pit latrine. She was pushed, by a State that decided it had more important issues to deal with. In 2014, five-year-old Michael Komape did not fall to his death. He was murdered. In 2018, five-year-old Lumka Mketwa did not fall to her death. She was murdered.

And then the speeches began. The South African Human Rights Commission pronounced, “Only three years after the tragic and preventable death of 5-year-old Michael Komape‚ the failure of the State to prevent a reoccurrence and to eradicate the prevalence of pit latrines in schools is unacceptable.” Basic Education Minister Angie Motshekga expressed “shock”, “The death of a child in such an undignified manner is completely unacceptable and incredibly disturbing.” The provincial education spokesperson first noted that the Executive Council had donated to the child’s funeral and then went on to say that what was truly “shocking” was that Luna Primary is “a state-of-the-art school, with good toilets” and yet, somehow, pit latrine toilets. Everyone is “shocked.”

According to the most recent National Education Infrastructure Management System report, published in January 2018, 37 Eastern Cape schools have no toilets whatsoever. None. 1,945 Eastern Cape schools have plain pit latrines, and 2,585 have so-called ventilated pit latrines. The Eastern Cape has 5393 schools.

Of the nine provinces, only the Eastern Cape has schools with no toilets whatsoever. But, of the 23,471 schools under the aegis of the national Department of Basic Education, 4358 have only pit latrines. KwaZulu-Natal’s 5840 schools boast 1337 schools with only pit latrines, while of Limpopo’s 3834 schools, 916 have only pit latrines. Of the 4056 schools in Gauteng, the Northern Cape and the Western Cape, none has only a pit latrine. None. Zero. This is the state of the art.

Lumka Mketwa’s family has serious questions. We all should have serious questions, rather than hollow condolences. Let’s start with the children who have not yet fallen to their deaths into schoolhouse pit latrines. At the very least, where is the map of these latrines? Where is the actual action plan to remove all of those death traps? Where is the Day Zero for school house pit latrines? Why is this not a national emergency? How many more children have to die and how many more families have to be haunted? Michael Komape’s family is haunted, to this day. Lumka Mketwa’s family is haunted. The State is not haunted. If it were, it would act.

“Her name is Lumka Mketwa and she is five years old.” She now resides in that city without a name where so many children are dead. Which children? Which childhoods? Who will honor Michael Komape? Who will honor Lumka Mketwa?

(Photo Credit: Times Live)