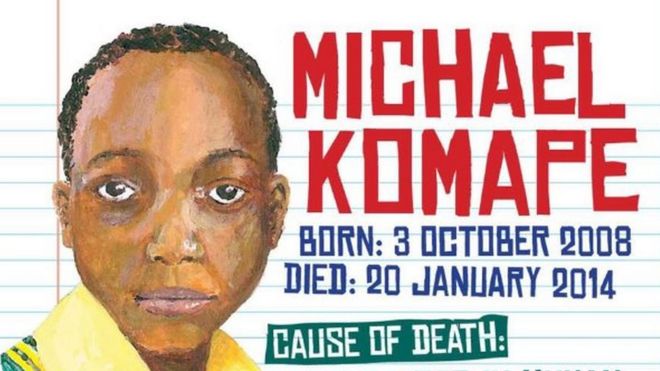

On January 20, 2014, Michael Komape, five years old, went to the toilet in his primary school in Limpopo, in South Africa. He never returned. The toilet seat was corroded, gave way, and Michael Komape fell into the pit and drowned to death in feces. Three years later, his parents and siblings have received neither apology nor support from anyone in government. His parents sued the Minister of Basic Education, and that trial began last week. Today, the court heard that the Department of Basic Education had been warned numerous times about the dangerous condition of toilets in Limpopo schools. The Department did nothing. The Department received three series of warning letters, in 2004 and 2008 and 2009, that described the school’s toilets as dangerously sinking. The State did nothing. Doing nothing means refused to act. Michael Komape did not fall to his death in a pit latrine. He was pushed, by a State that decided it had more important issues to deal with. In 2014, five-year-old Michael Komape did not fall to his death. He was murdered.

The afternoon of January 20, 2014, the school called Michael’s mother, Rosina Komape, to tell her that Michael was “missing.” Rosina Komape went to the school, and a classmate of Michael’s told her that Michael had last been seen going to the toilet, an outside pit latrine. School officials denied this, and claimed that Michael had gone out to play. Rosina Komape told the classmate to take her to the toilets: “When I looked inside the toilet I saw Michael’s hand. I then said that my child died asking for help … I asked them to pull him out by the hand maybe we can save him. I thought if we pulled him out we could save him. The principal said they had called someone to pull him out. I thought he was still alive and if we pulled him out and took him to hospital he would get help.” Michael Komape drowned in a pool of human feces, reaching to the sky. His mother came and found his outstretched arm.

The family is traumatized by and angry with the State. Days of testimony have revealed what we already knew, that the family of parents and siblings is grieving and living with nightmares, that the State has steadfastly stood fast and never extended any kind of hand to the family, and that this was a death foretold. In South Africa, 4624 schools have pit latrines.

The family is haunted, but not the State. Why not? While this story is particular to South Africa where it is seen as yet another referendum on the state of the democracy, and the human heart, it sits with similar stories around the world. It’s the story of neoliberal development, centered on global cities. Walk the streets of the Cape Town or Johannesburg or Washington, DC, metropolitan centers, and you will see extraordinary change taking place. Buildings go up, streets are torn up to lay underground cables, mansions rise where once modest homes sat, shopping malls and boutique shops proliferate, and the list goes on. Who pays for that? Michael Komape, Michael Komape’s brothers and sisters, Michael Komape’s mother and father. Last Wednesday, James Komape, Michael’s father, said, “They should have helped. My son was going to school. I did not send him to die.” I did not send him to die, and yet he was sent to his death, by a State that prefers waterfront malls to safe and secure school toilets.

Someone once wrote “Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear … twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.” Today, the first time is tragedy, and the second horror. Michael Komape did not fall, and his death, however painful and haunting, was not tragedy. Michael Komape was murdered, and, other than the family, who today is haunted? Who is haunted by the dead of Marikana, by the dead of Life Esidimeni, by the dead five-year-old child drowning in a pool of shit, reaching to the sky? When we look, do we see Michael’s hand? We should have helped.

Michael Komape two months before he died