In the United Kingdom, the Prison Reform Trust recently released its report, Resetting the approach to women’s imprisonment, which it describes as follows: “This briefing sets out the latest facts about women in contact with the criminal justice system in England and Wales. It contains statistics on the number of women imprisoned, the characteristics of women in prison and the drivers to their offending, as well as information about community-based services and solutions.” The only problem with this description is that many of the imprisoned women have not committed any offense. They are remand prisoners, women awaiting trial, women presumed innocent until proven guilty, women awaiting their day in court, their encounter, however brief, with due process.

According to the report, “The number of women in prison, especially on remand and on short sentences, has remained stubbornly high …. On 30 December 2024, 26% of women in prison were being held on remand. Almost nine in 10 women on remand are considered a low to medium risk of serious harm to the public. In 2023, 3,622 women were remanded into custody from the Magistrates’ Courts, of which 32% went on to receive a custodial sentence. By contrast, 2,639 women were remanded into custody from the Crown Courts and 54% went on to receive a custodial sentence. In 2023, 26% of self-harm incidents by women in prison were by those held on remand.”

Finally, despite the ongoing crisis of incarcerated women’s self-harm, they continue to be remanded to prison “for their own good”: “Women in contact with the criminal justice system who are considered to be in ‘mental health crisis’ are being remanded to prison for their ‘own protection’ or ‘as a place of safety’.”

While all of this is distressing and alarming, none of it is new or surprising, and therein lies the both the real crisis and the real shame. Consider the following, from these pages.

December 5, 2024: “According to the Howard League, “`proportion of women on remand is both higher than in the men’s estate and growing at a faster rate, and vulnerable women are still remanded to custody as a ‘place of safety’, while the government is struggling to keep women in prison safe …. Over half of the receptions into prison are of women on remand and a third are of women serving short sentences.’ Finally, according to arecent report from the National Police Chiefs’ Council, “Proportionately, more women than men are remanded in custody, and women remanded in custody at Crown Court are much less likely to go on to receive a custodial sentence than men (52% vs 71%).”

January 17, 2023: “Two-thirds of the women remanded to prison are found not guilty or given a community outcome. There are little to no services in the remand sections of prisons, and yet “acutely mentally unwell women” are remanded to prison, often.”

September 29, 2014: “Between 1997 and 2007, there was a 40% increase in the number of women in prison awaiting trial. In the same period, men prisoners awaiting trial decreased by 11%. More than 40% of women prisoners awaiting trial have attempted suicide at some point in their lives; for men that number is a little over 25%. Nearly two-thirds of women remand prisoners suffer from depression, a figure far higher than that of sentenced women prisoners. Half of all women on remand receive no visits from their family (for men, that number is 25%).”

Since at least 1997, the issue of the high incidence of women remand prisoners and of the mental health of many of those women has been pretty much public knowledge … and yet, decades later, here we are … again: “On 30 December 2024, 26% of women in prison were being held on remand. Almost nine in 10 women on remand are considered a low to medium risk of serious harm to the public.”

Part of the issue here is the gender constitution of due process.

In the United States, we hear and read and talk a great deal these days about due process, as it is being assaulted, battered, besieged by the current presidential administration. The concept itself first seems to have arisen in the Magna Carta. Clause 39 of the original 1215 version of the Magna Carta reads, “No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any other way, nor will we proceed with force against him, or send others to do so, except by the lawful judgment of his equals or by the law of the land.” Subsequent editions of the Magna Carta were shortened, and so, in 1354, Clause 39 became Clause 29, “No man of what state or condition he be, shall be put out of his lands or tenements nor taken, nor disinherited, nor put to death, without he be brought to answer by due process of law.”

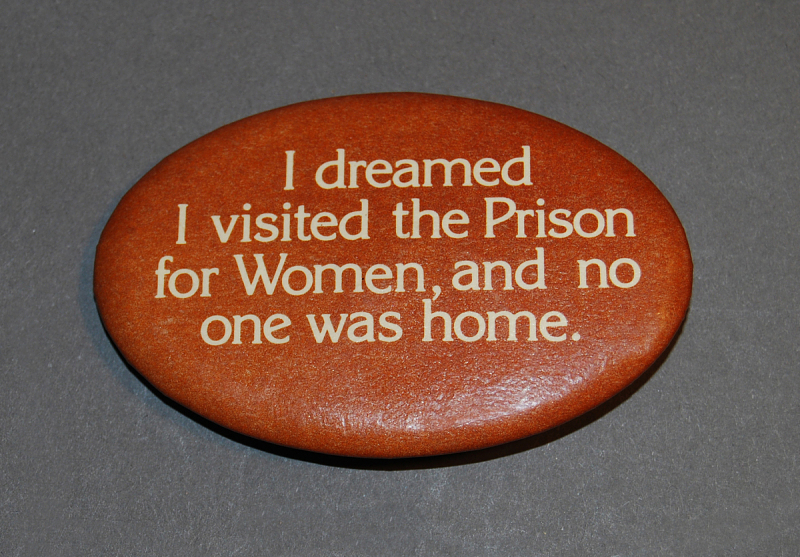

Whatever the earlier, and later, authors may have meant by “man”, the practices of the State in terms of women make it clear that the centuries old exclusion of women continues, in the courts, in the police stations, in the prisons and jails, as well as in the streets. Women are disproportionately remanded to prison because they are women, because as women they are excluded from any sense of due process. Women haunt due process.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Image Credit: Smithsonian)

_LRG.jpg)