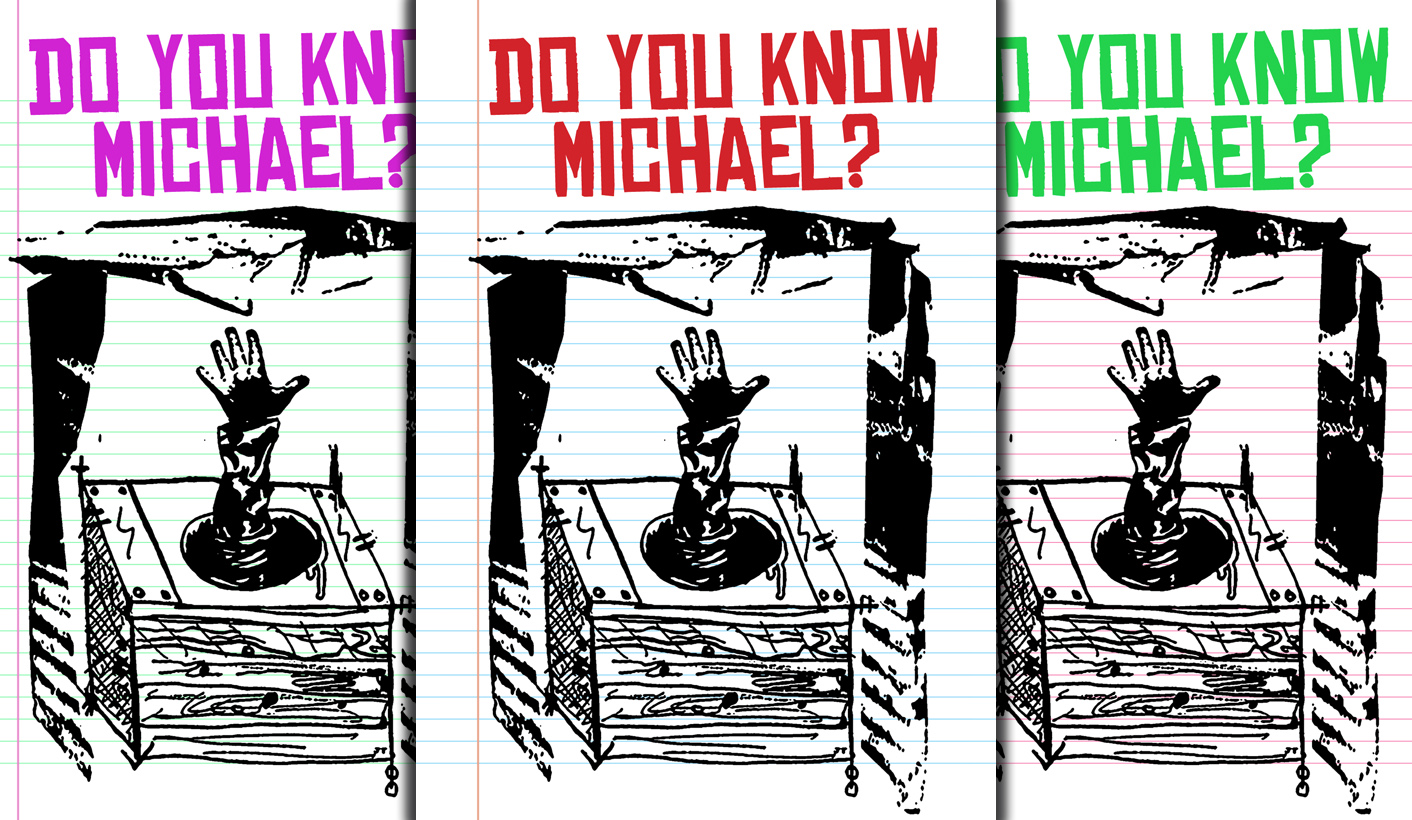

His hands were up

His hands were up

He was reaching out

So remarks the presenter

interviewing Section 27

on morning SAFM radio

His hands were up

five year-old Michael Komape’s

he drowning in a pit toilet

(learners and teachers

forced to learn and teach

in the state we are in)

His hands were up

He was reaching out

Now there is justice

some 5 years later

his family awarded

damages for emotional

shock and grief

A most appalling

and undignified death

says the judgement

(Supreme Court of Appeal)

The SAFM interview also

tells us of the insensitivity

and callousness of officialdom

in this regard

(have we lost our principles

along with so much else)

His hands were up

He was reaching out

How many more

See “Michael Komape’s family awarded R1.4 million in damages by appeal court” (Franny Rabkin, Mail & Guardian, 18 December 2019), and “Komape family awarded R1.4 million for emotional shock and grief” (Ciaran Ryan, 18 December 2019 © 2019 GroundUp).

The Komape family was represented by public interest law firm SECTION27

(Image Credit: Daily Maverick)