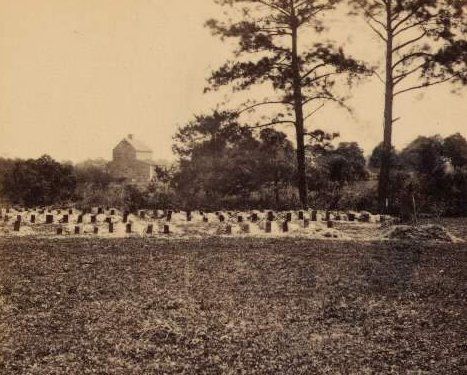

This April 1865 photo shows the graves of Union soldiers who died at the Race Course prison camp in Charleston, which would later become Hampton Park. On May 1, 1865, former slaves gave the fallen a daylong funeral

Today is May 25, 2009. In the United States, it’s Memorial Day, the last Monday of May, a day meant to honor those U.S. women and men who died in military service. Not all deaths are equal, and not all are equal in death.

Mary Clare Lindberg’s son, Benjamin Jon Miller, killed himself, as have many U.S. soldiers who have fought in Afghanistan and/or Iraq. Benjamin Jon Miller’s name is not on his unit’s Memorial Wall: “In March, Lindberg made a pilgrimage to Fort Campbell, Ky., to visit the post where her son served with the 101st Airborne Division. While it was comforting to meet with the soldiers with whom her son had served, Lindberg was upset when she saw the unit memorial. The names of two soldiers from her son’s brigade who were killed in combat were on the memorial, but Ben Miller’s name was not.”

Kyle Harper was engaged to Michael Hullender. Michael Hullender was killed in Iraq. Kyle receives no recognition, she finds “herself floating in legal limbo, with no rights to his effects or his name. Even in a bureaucracy as large as the Army, there is no form you can fill out to verify love, to explain the messy details of life; only the marriage certificate counts. As a result, the military had to treat Kyle the way it does all fiancees — as though she had no relationship with Michael. All the Army could offer were condolences. There would be no grief counseling, no casualty pay, no say in his burial….The military does not keep statistics on engaged soldiers or their partners.”

Walls without names, documents unsigned. Memorial Day.

Some say Memorial Day was begun by former slaves, 144 years ago, in Charleston, South Carolina: “Charleston was in ruins. The peninsula was nearly deserted, the fine houses empty, the streets littered with the debris of fighting and the ash of fires that had burned out weeks before. The Southern gentility was long gone, their cause lost. In the weeks after the Civil War ended, it was, some said, “a city of the dead.” On a Monday morning that spring, nearly 10,000 former slaves marched onto the grounds of the old Washington Race Course, where wealthy Charleston planters and socialites had gathered in old times. During the final year of the war, the track had been turned into a prison camp. Hundreds of Union soldiers died there. For two weeks in April, former slaves had worked to bury the soldiers. Now they would give them a proper funeral.”

Former slaves, Black women, men, children, descendants of Africans, marched and dug for the White prisoners who had died in the struggle to end slavery. Memorial Day was born out of the carnage of civil war, out of the labor and solidarity of emancipated slaves, out of the devastation of prison. Memorial Day begins just past the crossroads of empire, slavery, capitalism, racism, civil war, nationalism, patriarchy, violence, sexism. That’s one hell of an intersection, but if Memorial Day started with African-derived formers slaves gathering, marching, and taking of care of business, it should be located at the intersection of truth and reconciliation. It should be. The slaves’ names will not appear on any wall, they will not be legitimated by any document. Today, May 25, 2009, is African Liberation Day. What would those former slaves, Black daughters and sons of Africa, say, and what would those White prisoners say in response?

(Photo Credit: Library of Congress / PostandCourier.com)