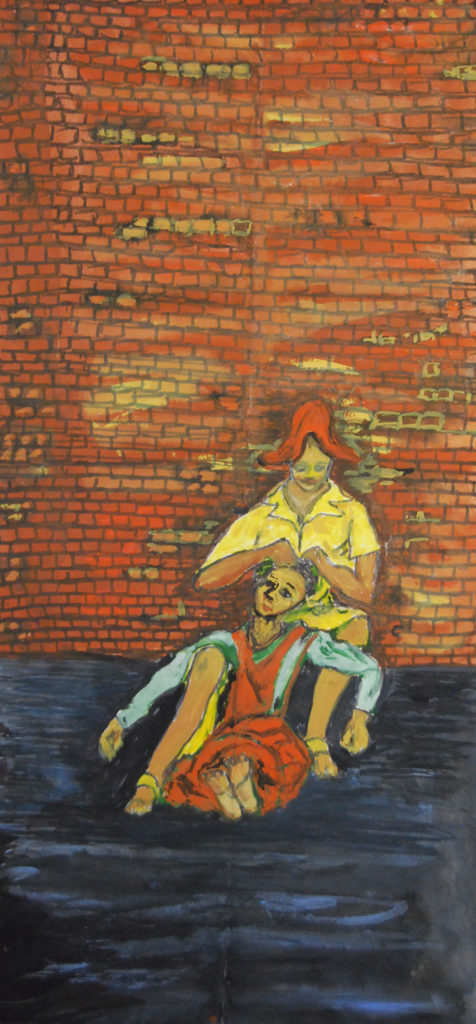

Irlanda Jerez

On July 17, the government of Nicaragua celebrated el Día de la Alegría, the national Day of Joy which honors the day in 1979 when the dictator Anastasio Somoza Debayle fled the country. This year, on July 17, the State sent soldiers and paramilitaries into Masaya, the protest or rebel city, and “regained control.”That control cost more than 300 dead and untold injured, wounded, scarred, violated, tortured, and traumatized. On July 18, woman human rights defender Irlanda Jerez was abducted by hooded, armed State agents and dumped in jail. Irlanda Jerez’s “crime” was having lead merchants in the Mercado Oriental, Nicaragua’s largest marketplace, in a campaign in which merchants refused to pay taxes in protest of Nicaragua’s violation of human, women’s, and civil rights. Irlanda Jerez was abducted, dumped in jail, processed through a fake court hearing the next day, July 19, and condemned to five years in prison. Irlanda Jerez was sent to La Esperanza prison, near Managua, where she sits with other women political prisoners and where she and others have been beaten. Irlanda Jerez continues to speak out, continues to not accept the current repression as inevitable. The United Nations, the Inter-American Commission for Human Rights and others have condemned the violence committed against Irlanda Jerez and her sister comrade prisoners. Where is the global media on Nicaragua’s abuse of Irlanda Jerez? Where is the global outrage at the abuse of Irlanda Jerez?

On July 19, Irlanda Jerez entered La Esperanza prison. On October 26, around 4 pm, four masked, armed men dressed in black came into Irlanda Jerez’s cell and demanded that she come with them for interrogation. She refused. Irlanda Jerez and her cellmates resisted any attempt to seize Irlanda Jerez. At around 6 pm, a larger group of unidentified, disguised armed men swarmed the cell and beat Irlanda Jerez and her cellmates. Finally, after three hours, Irlanda Jerez agreed to leave the cell. Behind her, one cellmate lay unconscious and the others were battered and bruised. No medical attention was ever provided.

The men told Irlanda Jerez they intended to transfer her to solitary confinement at La Modelo men’s prisons. When Irlanda Jerez did not return quickly to her cell, prisoners across La Esperanza raised a hue and cry, and Irlanda Jerez was finally returned to her cell.

On October 30, Daniel Esquivel, Irlanda Jerez’s husband, was allowed to visit. On the same day, prison authorities refused admission to members of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and the Permanent Human Rights Commission.

According to Ana Maria Tello, coordinator of the Special Follow-Up Mechanism for Nicaragua, MESINI, there are currently more than 400 political prisoners in Nicaragua. MESINI is particularly concerned about the health and safety of Irlanda Jerez and her cellmates, including Amaya Eva Coppens Zamora, Olesia Auxiliadora Muñoz Pavón, Tania Verónica Muñoz Pavón, Solange Centeno Peña, María Dilia Peralta Serrato, and Nelly Marilí Roque Ordoñez. Meanwhile, according to the Nicaraguan Center for Human Rights, in the first ten days of November, 32 people were illegally detained. The war and the struggle continue.

On July 19, Irlanda Jerez’s sister, Dolma Jerez went to the gates of the prison to demand the release of her sister and much more: “We are demanding justice and freedom for my sister and not only for my sister but for the thousands of detainees who have been accused and have been deprived of their freedom only for speaking out.”

Why is the global media not speaking up as well? Where are the reports concerning Irlanda Jerez and her sister comrades; the conditions of women in Nicaragua’s prisons and jails; the constant threat to free speech and expression and to the right to association; Nicaragua’s State violence against women; and the levels of State repression in Nicaragua more generally? When the world acquiesces to the reign of terror and silence currently exercised in Nicaragua, what happens to Irlanda Jerez happens to all of us. Why is the world news media silent on Nicaragua’s abuse of Irlanda Jerez and her sister comrades? Where is the global outrage at Nicaragua’s abuse of Irlanda Jerez?

(Photo Credit: La Prensa)